Make Nitrogen Work for You, Not Against the Climate

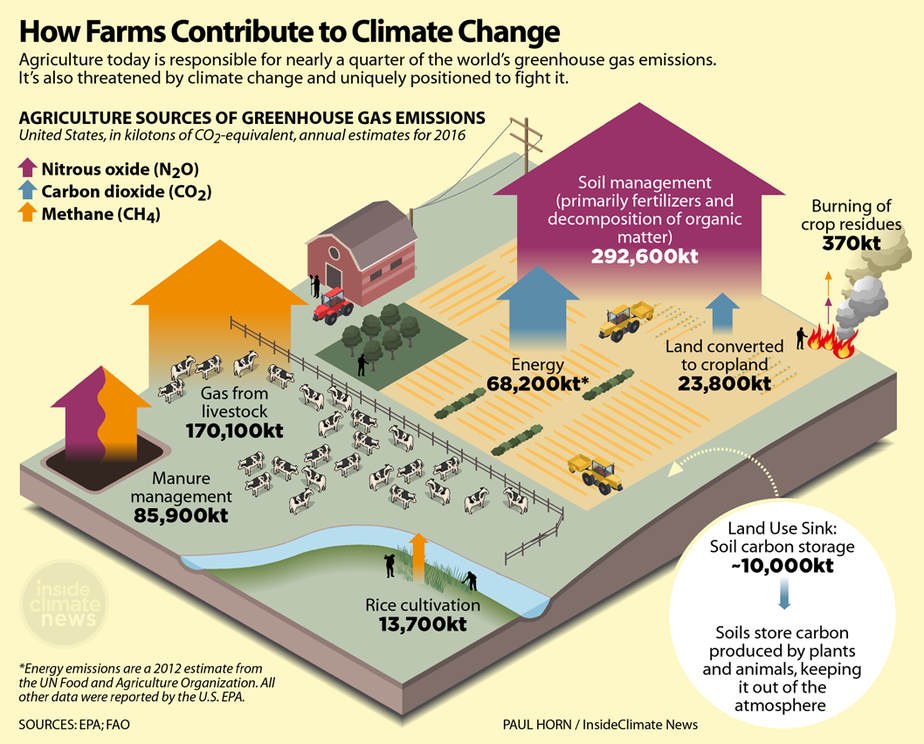

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, soil management practices contribute 68% of total agriculture industry greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Tillage and nutrient management influence microbial interactions which cause nitrogen (N2) or nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions through denitrification. Remember our friend, the Nitrogen Cycle? Microbial organisms mineralize nitrogen into usable forms for plant uptake. Depending on weather patterns, these forms can either leach or escape into the atmosphere. Unfortunately escaping N2O can survive in the atmosphere for over 100 years and has a global warming potential 300 times greater than carbon dioxide (CO2). While we can’t abandon fertilizers outright due to increasing food demand, we can optimize nutrient management strategies. A concept called the 4R’s of Nutrient Management: Right Source, Right Rate, Right Time, and Right Place was developed to optimize the industry’s approach. These four components rely upon each other to maximize yield potential, economic opportunity, and reduce negative environmental impacts.

Right Source – This is the fertilizer selected to meet plant nutrient needs, considering soil chemical and physical properties, nutrient interactions, fertilizer blend compatibility, and nutrient forms available to the plant. When considering nitrogen sources there is not a significant difference between fertilizer source and increased N2O emissions, but varying site conditions may be a factor. Wet weather may enhance the denitrification process, leading to greater nitrogen losses. Utilizing slow release fertilizers or nitrogen stabilizers may reduce these losses. Manure applications were shown to have higher N2O and CO2 emissions compared to inorganic fertilizer sources. The largest emission contribution comes during the manufacturing processes, where ammonium nitrate production causes higher methane (CH4), N2O, and CO2 emissions compared to the production of ammonia and urea.

Right Rate – Discusses the amount of fertilizer applied, ideally determined by crop nutrient needs and soil test results. Determining appropriate nitrogen rates is a difficult task that comes down to a balance between the credit from the previous year’s crop, how much the crop can uptake, and economics. If nitrogen applications exceed optimum rates, then excessive nutrients may increase GHG emissions and groundwater leaching. Due to rate concerns the Tri-State Fertilizer Recommendations for Corn, Soybeans, Wheat, and Alfalfa were developed. Further, each state has different protocols tying fertilizer costs, grain prices, and optimum rates for particular regions.

Right Time – Applying nutrients when needed. Plant growth characteristics, nutrient deficiencies, soil characteristics, weather forecasts, and planting dates should be considered. Limiting the time nutrients spend in the ground before uptake results in less loss. Whether doing a preplant application or side-dress, producers follow this practice to provide timely nitrogen as the crop needs it. Additional applications throughout the growing season may be necessary. Fall nitrogen applications should be avoided.

Right Place – Placing nutrients where crops can access the plant-available form. Placement is dependent on several factors: plant genetics, technology, tillage practices, plant spacing, crop rotations, and weather. Global Position System (GPS) technology has improved and helps prevent skips and over-application. Considering in-furrow, pop up, or 2x2 placement can improve crop use efficiency. Regarding application depth, shallower applications can reduce N2O emissions by 26 percent. It was reported that emissions were lower with 4-8” application depths compared to deeper 12” placement. However, surface applied urea also showed increased N2O emissions compared to shallow applications indicating some soil incorporation was beneficial.

Above: This graphic shows several ways synthetic fertilizers contribute to climate change and environmental degradation: 1) soil microbial conversion of nitrogen fertilizers to nitrous oxide (a potent greenhouse gas), 2) nitrate runoff into water bodies fueling algal blooms, 3) leaching of nitrates into the soil and contaminating groundwater, and 4) greenhouse gas emissions from the manufacturing of synthetic fertilizers. This graphic appeared in an October 2018 article from Inside Climate News by Paul Horn.

Implementing the 4R’s of Nutrient Management makes practical sense as it may reduce input costs and it benefits the environment. There are many resources available if you are considering implementation. All are encouraged to check out the Tri- State Fertilizer Recommendations for Corn, Soybeans, Wheat, and Alfalfa. The Fertilizer Institute's Nutrient Stewardship resources are also an excellent starting point.

References:

Adair, E. Carol, Barbieri, Lindsay, Schiavone, Kevin, and Darby, Heather M. "Manure Application Decisions Impact Nitrous Oxide and Carbon Dioxide Emissions during Non‐Growing Season Thaws." Soil Science Society of America Journal 83.1 (2019): 163-72. Web.

Drury, Craig & Reynolds, Daniel & Tan, Chin & Welacky, T. & Calder, W. & Mclaughlin, Neil. (2006). Emissions of Nitrous Oxide and Carbon Dioxide: Influence of Tillage Type and Nitrogen Placement Depth. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 70. 10.2136/sssaj2005.0042.

Flynn, H.C. “Agriculture and Climate Change: An Agenda for Negotiation in Copenhagen – The Role of Nutrient Management in Mitigation”. 2009. Web.

Schahczenski, J., and H. Hill. 2009. Agriculture, climate change, and carbon sequestration. ATTRA-National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service.

Stinke, K., Snapp, S.S., “Climate Change and Soil Management in Field Crops.” Extension Bulletin E-3187 (2013). Michigan State University Extension. Web.

The Fertilizer Institute. The Nutrient Stewardship – 4R Pocket Guide. Web.

Farming a Better Climate is written in collaboration by the Indiana State Climate Office, Purdue Extension, and the Purdue Climate Change Research Center.

If you have questions about this series, please contact in-sco@purdue.edu.