Reducing Methane through "MyPlate" for Ruminants

Companies are already trying to profit from marketing climate-friendly beef, but are the companies’ claims accurate, and will these efforts provide new opportunities for producers? To understand how difficult an issue this is to navigate, it’s useful to look at a recent social media ruckus. In a commercial online, a young country singer yodeled a tune about how the beef animals that Burger King sources would be fed with lemongrass, which would help the climate by reducing the amount of methane burped up by the cattle. The immediate feedback online was largely negative. The article Burger King referenced had not yet been peer reviewed. Many other researchers have looked at feed supplements with less rosy results. The cattle were only fed lemongrass additives during the last three months of their lives, so life cycle analysis fans pointed out that three months of a 33 percent emissions decrease totals out to a reduction of only around 3 percent over the lifespan of a steer. Here, we try to look past the hype and the noise. Are diet supplements for cattle a realistic way to reduce the carbon footprint of agriculture?

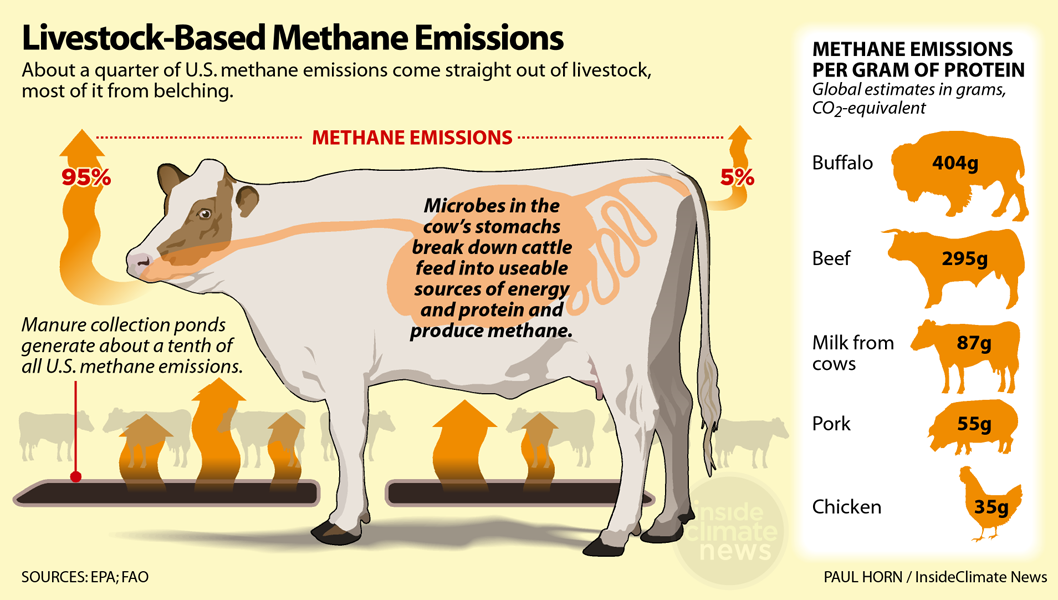

To understand whether cattle emissions can be meaningfully reduced by supplements, it’s useful to understand how and why cattle give off greenhouse gases. Ruminants such as cattle, goats, and sheep have four stomachs: the rumen, the reticulum, the omasum, and the abomasum. The first stomach, the rumen, serves to ferment the feed for easier digestion later. The fermentation process occurs in a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Those bacteria release methane. The methane is then breathed out of the mouth while the ruminant chews its cud. Of methane emissions from ruminants, 95 percent come out of the mouth. Although cows fart, the idea that this is the main source of methane is false. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, these types of ruminant emissions account for 39 per cent of total agricultural emissions. Agricultural emissions are 14.5 per cent of total global climate emissions. So a little simple math tells us that enteric fermentation (ruminant emissions from the mouth) accounts for 5.6 per cent of total global carbon emissions. That’s not zero, but also not the main contributor to increases in greenhouse gas concentrations.

Left: Livestock produce methane when they digest their food, and release most of it through belching. A cow’s diet affects the amount of methane it produces. Researchers have found that some diet supplements such as seaweed and lemongrass can cause cows to produce less methane. This graphic appeared in an October 2018 article from Inside Climate News by Paul Horn.

Using feed additives to reduce the emissions from cattle mouths is tricky. The additives have to decrease the methane output of the microbes in the rumen without killing those microbes. The pH of the rumen needs to be held between neutral and slightly acidic. A wide range of additives have been studied, but the most promising appear to be lemongrass, peppermint, garlic, and seaweed. Of these four, seaweed seems to have the best results. A recent paper’s title says it all: “Red seaweed (Asparagopsis taxiformis) supplementation reduces enteric methane by over 80 percent in beef steers” (You can see the paper in the scientific journal PLOS ONE.) But there are some problems: additives like this don’t taste great to cattle, and it’s only practical to deliver them with the feed provided on feedlots, where the steers spend a small portion of their lives. Also, seaweed would be rather hard to find in Indiana!

The consumer would love to have inexpensive meat options that also have less of a carbon footprint. If scientific breakthroughs in feed additives can help farmers reduce this footprint, they would adopt those practices. Promising feed additives may be coming, but there still isn’t a perfect solution for reducing cattle emissions.

Farming a Better Climate is written in collaboration by the Indiana State Climate Office, Purdue Extension, and the Purdue Climate Change Research Center.

If you have questions about this series, please contact in-sco@purdue.edu.