The Scoop On Poop In A Changing Climate

In pastoral agricultural days, and on some farms around the state today, cattle, pigs, turkeys, and chickens roamed the countryside, held in relative place using fencing or a centralized food source. Their manures were deposited on the pastures they roamed, and nutrients therein fertilized those soils. Today, these animals in particular tend to grow in confined operations, be they buildings or feedlots. One result of this management practice is the need to control and position waste that falls on dirt or concrete floors rather than pastures. The way in which those manures are handled have a big effect on the emission of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere.

As was mentioned in a prior article, the emission of methane in agriculture is majority-caused by rumen digestion out of the mouth of cattle, sheep, goats, and others with four stomachs. However, methane emissions from manure management are second in rank across research studies. Generally, manures from livestock management are channeled away from the animals and placed into pits, lagoons, composted, or hauled off site for spread onto agricultural fields. Greenhouse gas emissions, no matter the management practice, can be reduced by using some practical and often economically viable steps.

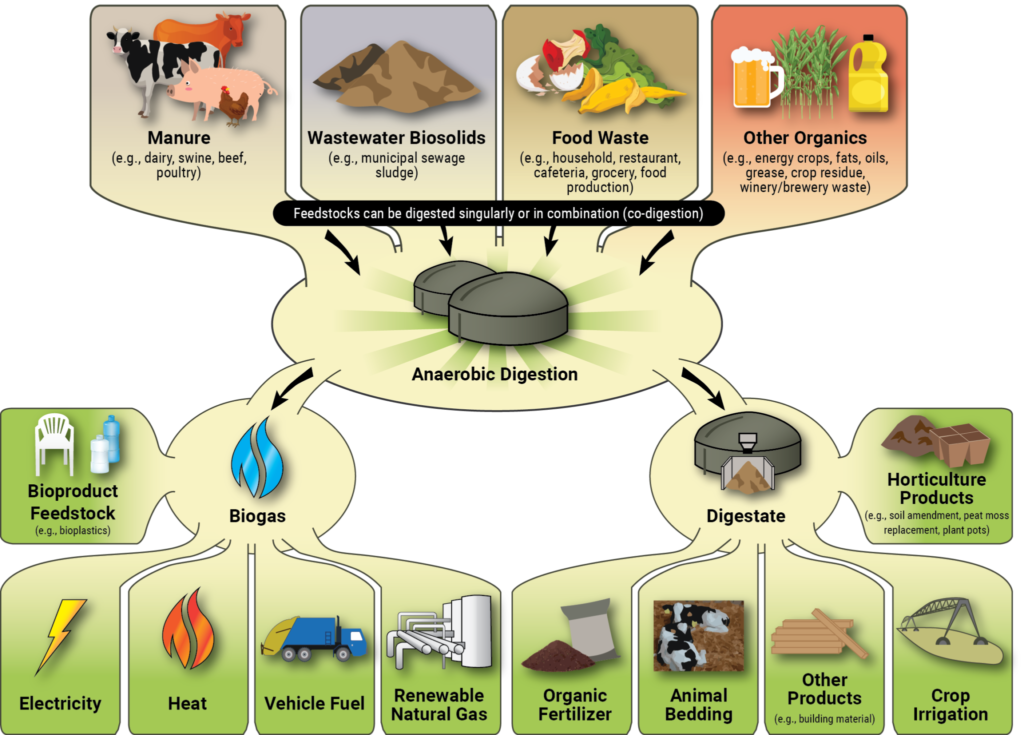

Anaerobic digesters on confined feeding operations are one expensive yet potentially lucrative option for controlling animal waste. Waste is fed into a closed system where bacteria break down the excrement into biogas and digestate. The biogas contains concentrated methane, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and other trace gasses. This biogas can then be converted to natural gas and reused for fuel. Although not completely clean from a greenhouse gas perspective, anaerobic digestion does create an opportunity to reduce total emissions through reuse. The EPA has an excellent primer on digesters.

Above: The figure illustrates the flow of feedstocks through the anaerobic digestion system to produce biogas and digestate. SOURCE: U.S. EPA

If planning to spread manures on agricultural fields, incorporation of those manures into dry soils at or very shortly after application makes a huge difference in the amount of gasses that enter the atmosphere. As Hristov et al. found in 2011, referenced in the Sustainable Dairy Fact Sheet Series, incorporation of manure can reduce ammonia emissions from those manures by 70 percent. Nitrous oxide emissions can likewise be reduced by ensuring that manures are applied and incorporated into dry soils, as moisture enhances the conversion into nitrous oxide gas.

Lagoons provide an open storage structure for liquid and solid waste, with their cleanout occurring on timed intervals and lagoon wastewater applied to nearby agricultural fields. When possible, use of a lagoon cover digester provides significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Recent research into lagoon additives also shows some promise in reducing emissions, and many different kinds are currently being marketed. In the absence of a cover digester, just getting the lagoon covered can reduce gas emissions. Finally, aeration of the lagoon turns anaerobic conditions into aerobic conditions, which may increase carbon dioxide emissions, but reduces methane, hydrogen sulfide, and nitrous oxide emissions.

However manure is managed, using current best management practices to keep greenhouse gases out of the air and in forms best turned into a profit through conversion to nutrients or natural gas, helps keep agriculture running at maximum efficiency. For more information on manure management, contact Purdue Extension’s Hans Schmitz at hschmitz@purdue.edu or 812-838-1331.

Farming a Better Climate is written in collaboration by the Indiana State Climate Office, Purdue Extension, and the Purdue Climate Change Research Center.

If you have questions about this series, please contact in-sco@purdue.edu.