Short-Stature Corn Hybrids: Next Evolution in U.S. Corn Production?

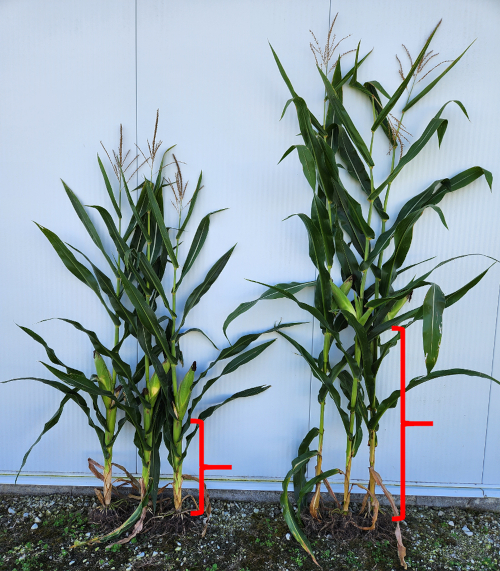

Lately, several prominent agricultural seed and genetic companies have started introducing novel corn hybrids characterized as “short-stature”. These hybrids are noticeably shorter than current “full-stature” hybrids and can often range 20 – 24 inches shorter in height (Figure 1). Overall, these hybrids have potential benefits which include increased lodging resistance, increased tolerance to higher plant populations, and narrower rows, and easier in-season access with spray equipment for fertilizer and pesticide applications. However, the introduction of these new hybrids raises many new questions for producers and consultants such as 1) how do these hybrids compare to current full-stature hybrids? 2) how well do these hybrids yield? 3) do these hybrids require higher optimum seeding rates? and 4) how challenging are these hybrids to harvest? etc. Therefore, new 2023 research at Purdue University in partnership with Bayer CropScience, one of the leaders in the introduction of these new hybrids, sought to answer some of these questions.

Figure 1. In-season comparison of full-stature corn hybrids (left) with short-stature corn hybrids (right).

In 2023, research trials at Purdue University comparing both short-stature and full-stature hybrids observed noticeable differences in both average plant height (67 inches vs. 86 inches) and average ear height (22 inches vs 37 inches, measured from the point where the ear shank attaches to the main stem), yet minimal differences in average aboveground total plant biomass (7300 vs 7200 lbs/ac) at the R1 growth stage. The reduced heights of short-stature hybrids are typically realized in the “stacked” internode-spacing below the ear (Figure 2). In addition, short-stature hybrids maintained similar leaf number and exhibited a wider stem diameter and a wider ear leaf diameter than full-stature hybrids, likely contributing to the lack of total biomass differences. Overall, these short-stature hybrids maintained very strong yields at both of the Purdue research locations in Indiana and produced the same or slightly lower yields in comparison to full-stature hybrids when grown in the exact same environments. For example, short-stature hybrid yields did exceed 300 bushels per acre within multiple research treatments and maintained average yields ranging from 240 – 260 bushels per acre in NW Indiana and 250 – 300 bushels per acre in central Indiana.

Figure 2. Observed visual difference in internode spacing below the ear in short-stature corn (left) compared to full-stature corn (right).

These hybrids also exhibited a higher tolerance to both increased seeding rates and narrow row (20-inch) systems. For example, research in both central and NW Indiana observed continued grain yield increases as seeding rates increased from 34,000 to 50,000 seeds per acre when grown in 20-inch rows, which suggests these hybrids may have the potential to tolerate even higher plant populations when grown in narrow row systems. Furthermore, agronomic optimum seeding rates for short-stature corn in 30-inch rows were often on average 6 – 8,000 seeds per acre more than current full-stature hybrids. Overall, these hybrids show tremendous promise in their ability to yield well and tolerate higher plant populations and narrower rows, however, many physiological and management questions still remain and will continue to be pursued.

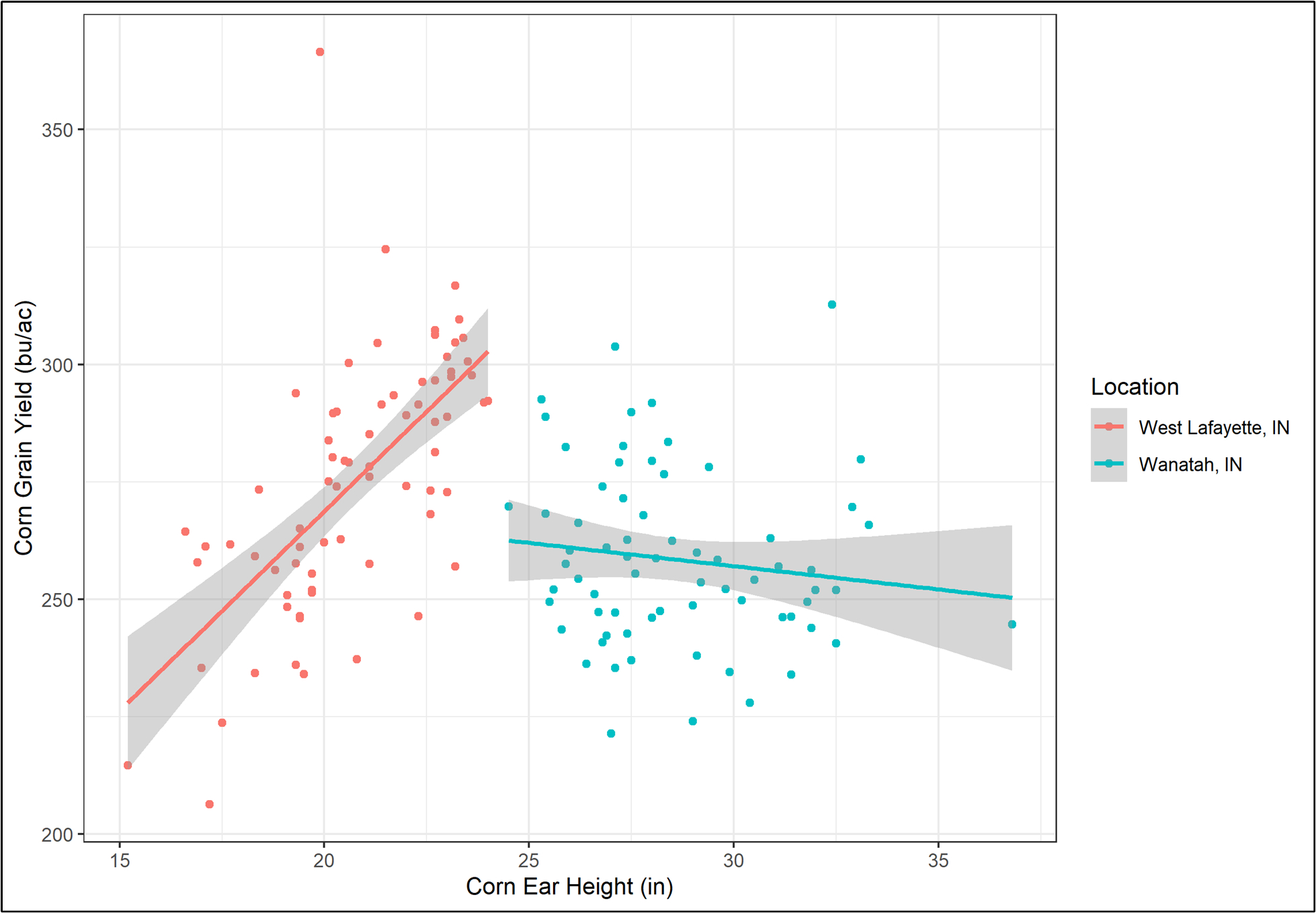

One of the biggest challenges these hybrids will continue to face will be both ear height and harvestability. Corn ear position on the main stem must maintain specific heights above the soil surface in order to be properly harvested by current combine headers and to avoid any added additional wear on machines. For example, 2023 research at Purdue observed a fairly strong relationship between ear height and yield once the height dropped below 23 – 24 inches, whereas the relationship to yield became much weaker when ear height was above this threshold (Figure 3). Based on 2023 research at Purdue, corn ear height was dictated by hybrid selection, planting date, growing season environmental conditions, and management practices, meaning each of these factors will remain important when adopting short-stature hybrids. Overall, these hybrids showcase the potential to improve U.S. corn production, improve resiliency to adverse weather conditions, and improve the ease and efficiency of in-season nutrient and crop protection applications. However, many questions still remain and further research will be required to fully understand this new corn hybrid system.

Figure 3. Relationship between corn ear height (measured from the soil surface to the point where the ear shank attaches to the main stem) and grain yield. Red points indicate data collected from West Lafayette, IN and blue points indicate data collected from Wanatah, IN.

Dan Quinn, PhD

Assistant Professor of Agronomy

Extension Corn Specialist

Purdue University

djquinn@purdue.edu

Erick Oliva

MS Graduate Research Assistant

Purdue University