Has the IRA made conservation a target in the Farm Bill debate?

May 5, 2023

PAER-2023-17

Roman Keeney, Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics

In August of 2022, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) into law, a reconciliation package that included numerous items carried over from the stalled Build Back Better agenda. The IRA package targets several health, energy, and climate policy areas with nearly $800 million in new spending. Included in that spending is some $40 billion in funds for agricultural programs – with half of those directed to expansion of farm bill conservation programs.

The 1985 Farm Bill established the conservation reserve program (CRP) with the objective of taking highly erodible land (HEL) out of production with auxiliary objectives of providing income support and reducing commodity supplies. In subsequent farm bills, the scope of conservation objectives has expanded dramatically. The 21st century has seen farm conservation programs increasingly focused on multi-objective criteria while shifting focus from land retirement to working lands approaches that favor conservation practices that deliver e.g., water quality or wildlife habitat alongside commodity production. Given this evolution of agricultural conservation, it is little surprise that mitigation of climate change would intersect the current suite of agricultural conservation efforts.

The IRA and the 2023 Farm Bill

IRA funds directed to USDA are intended to promote reduced greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) or promote resiliency of natural and economic systems to climate change effects. Four farm bill conservation programs are directly impacted by the IRA with additional funding in years 2023 through 2026[1].

Table 1. Farm Bill Conservation Spending Affected by the IRA

| Farm Bill Program | Farm Bill ’23

Baseline (Est.) (Billion dollars) |

IRA Increase

(Billion Dollars) |

| Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) | $22.28 | $8.50 |

| Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) | $11.35 | $3.25 |

| Agriculture Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) | $4.95 | $1.40 |

| Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) | $3.30 | $4.95 |

Source: CRS 2022 Outlook and CRS R47262

The estimated spending on the four farm bill conservation programs is given in table 1 with amounts added by the IRA[2]. The four-program budget impact is an increase of +30% with the largest increase in the regional conservation partnership program (RCPP) that offers grants for regional or watershed scale projects to restore soil, water, and/or wildlife habitat resources. Both EQIP and CSP are workhorse voluntary conservation programs employed to technical and cost-share assistance with on-farm projects that enhance environmental outcomes. ACEP is an easement program that targets areas for protection or restoration primarily focused on wetlands.

The IRA’s focus on working lands programs while making no changes to the more prominent CRP reflects the policy trend away from long-term land retirement as well as the increased focus on the intersection of climate and agriculture. While the working lands programs in table 1 are evaluated on a wide range of environmental services (relative to cost), the wrinkle to the IRA is that new projects from these funds must address the subset of activities identified as “climate-smart” agriculture.

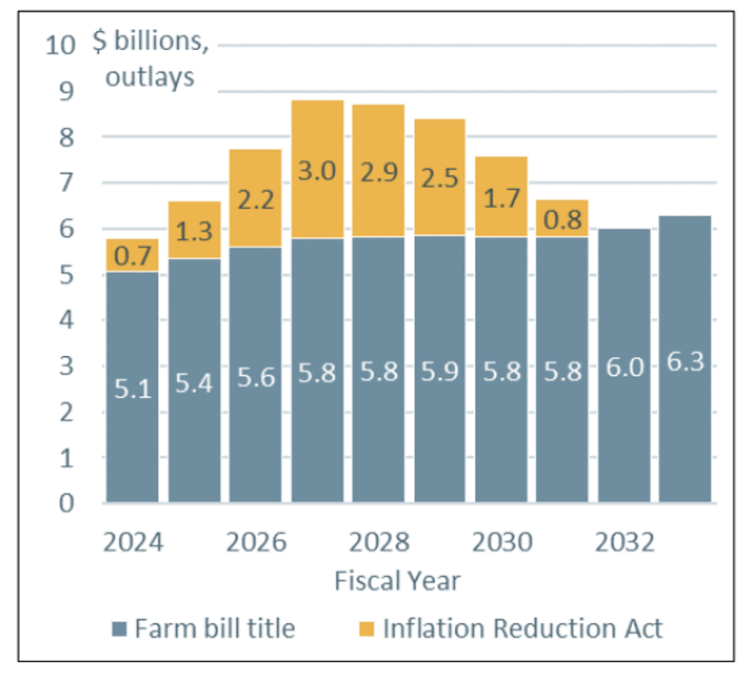

Figure 1. Conservation baseline estimates from CRS

Source: Image is taken directly from Monke’s (2023) Farm Bill Budget Dynamics published by CRS

From a farm bill perspective, the IRA additions will not be part of the funding baseline that emerges later this spring but will clearly have an impact on how legislators approach the conservation title (Title II) in constructing new omnibus legislation. Figure 1 is taken from CRS’s latest farm bill budget primer and depicts total projected spending for farm bill conservation spending split between the farm bill and IRA. The funding pattern shows the ramp up in conservation projects from 2024 to 2026 with spending increases in 2027 and 2028 when all project funds are estimated to be committed and eventually delivered through the end of authorization in 2031.

The IRA’s use of existing conservation programs makes for a unique situation where the agricultural committees could shift farm bill resources away from conservation spending during IRA years without affecting the overall size of these programs. The extent to which this path might be pursued depends on multiple factors, including priorities for funding in other farm bill titles, how well IRA signups match traditional farm bill conservation objectives, and the politics of the climate agenda itself.

Farm Bill and Climate Politics

The IRA approach to farm conservation programs reflects the tradition of voluntary participation and farm bill politics have an enduring tradition of passage with large bipartisan support. The IRA itself was passed with a single party vote as reconciliation legislation that required only majority support in both the House and Senate.

The uniform opposition by Republicans to the IRA did not reflect uniform opposition to the content of the bill, as many representatives have touted new projects and employment impacts in their home district. Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) recently published his caucus’ demands for raising the debt ceiling which calls for direct repeal of the IRA clean energy subsidies and indirectly impacts IRA funding with a call to reduce spending back to fiscal 2022 levels.

Once the debt ceiling is resolved, the politics of the farm bill debate should become clearer. A best-case political scenario is both political camps desiring a “we can work together” outcome relying on the traditional compromises that have shielded the farm bill from generic political intransigency. The worst-case scenario is that the farm bill becomes a proxy for the political debate on two larger agenda items – climate and the budget. In 2012, the farm bill became a pillar of the broader agenda fight over the size of federal government and languished under non-starter approaches such as stripping the nutrition title from the farm bill.

While the debate over the size of the government is predictable, positioning on the climate agenda is still evolving. Both major parties host a subset of lawmakers that see promoting or opposing climate action as a priority and have proven difficult to sway toward compromise positions. The newly installed Republican majority has included partial and total repeals of the IRA on the 2023 legislative calendar. These bills were filed with no prospects of becoming law, but they signal broad opposition to the preferred climate approach of Democrats. Of concern for agriculture, this sets up the conservation title as a potential confounding factor in farm bill passage.

Looking Ahead to Title II in the Farm Bill

Under normal conditions, it would be unusual for the conservation title to represent a sticking point in farm bill passage. Voluntary programs in the farm bill have been viewed favorably by farm and conservation groups as the protection of natural resources tends to dovetail with long run farm management goals. Attempts to repeal the IRA’s additions to agricultural conservation or undermine IRA climate goals in the farm bill process raises the specter of competing proposals to expand climate programming in title II. These could include more aggressive conservation compliance or relaxing land retirement caps that put a ceiling on the CRP. If climate politics become the effective model for delivering a new conservation title – it will add another major hurdle to what appears to be an already difficult year for farm bill passage.

[1] The 2026 end date for added budget spending applies to the commitment of funds to new projects and contracts. Funding committed by 2026 under the IRA authority must be expended by 2031. Because of the extended window to expend IRA funds the reconciliation bill itself has the effect of extending the authority for affected programs to 2031 meaning that they are not subject to the farm bill’s sunset provision at the start of fiscal year 2024.

[2] The farm bill spending here is the estimated continuation of the 2018 Farm Bill that would be used to calculate the 2023 Farm Bill baseline. These numbers are from the 2023 Congressional Budget Office Outlook and not the official baseline which had not been published at the time of this writing.