How does the farm bill get made?

January 18, 2023

PAER-2023-09

Roman Keeney, Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics

Whether it was High School civics or Schoolhouse Rock most of us have encountered a cogent explanation on the process of lawmaking. The basic story of Congress finding a compromise that merits passage and sending it to the president for signature or veto is simple enough – the effort to find that compromise is often quite complex. In this brief we outline the process we might expect to unfold in producing a 2023 Farm Bill given the current state of the agricultural economy and past experience passing farm legislation.

The baseline as starting point

The farm bill process has no definitive “starting point”. Many of the commodity support (and other) programs it establishes are written such that they expire after a period of five years. This temporary nature of programs provides a deadline for replacement so that policy-makers who are most active in drafting farm legislation will begin work on a new farm bill during the year prior to expiration. Holding hearings in congressional committees, participating in stakeholder listening sessions, or other ways of staking out positions on farm and food policy concerns are typically the first notices of lawmakers kick-starting the process.

The most concrete timeline item other than the expiration deadline for the farm bill is the publication of the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) baseline spending estimates for mandatory spending programs in the final year of current farm law. These spending projections are made using the assumption that current law extends forward ten years and typical congressional rules require that projected spending in a new farm bill not exceed that baseline budget. This expiration year baseline is sometimes referred to as a “scoring baseline” because CBO will use it to compare the expected spending changes over the coming ten years between old and new farm bill programs.

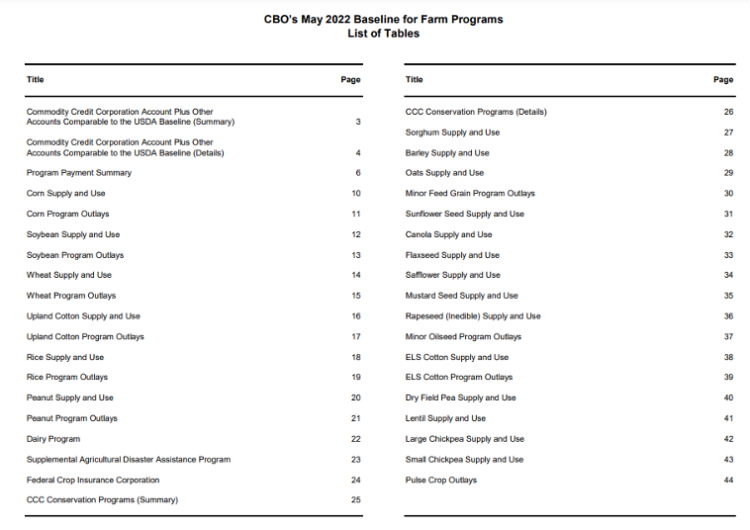

The CBO baseline is a large forecast model of government outlays for entitlement programs. Figure 1 depicts the table of contents (list of tables) from May 2022’s CBO baseline projection[1] and gives us an idea of the complexity of estimating economic trends that will trigger different levels of spending going forward. For example, in the table we see that page 10 reports the supply and use projections for U.S. corn markets over the coming ten years and then page 11 takes those market forecasts and applies policy rules to generate spending estimates. Any change in program rules for corn in a new farm bill would be applied to these same page 10 estimates of supply and demand and the change in program outlays represents the “score”[2] for this component of government spending.

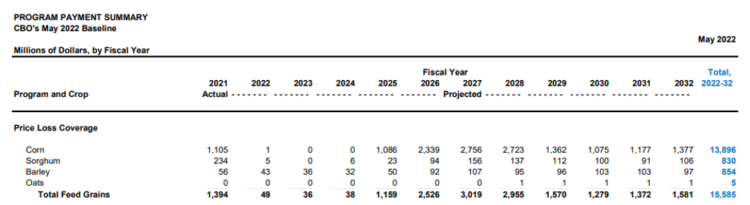

In figure 2, a partial table from CBO’s baseline shows the timeline of spending on feed grains projected from 2022 to 2032 alongside actual spending recorded for 2021. We can see from the projected support levels that the CBO model identifies quite low payments for feed grains from 2022 to 2024 before the prices assumed in the baseline start to decline enough to generate increasing payment levels that eventually return to the longer run average. These expected payment levels are the result of the specifications in the law that requires the use of either absolute reference prices (i.e. set by statute) or moving average prices from the past five years. Any change to the reference price or formula for calculating an average price in feed grains could potentially cause a change in the spending projections we see in figure 2.

Drafting farm legislation

Once a scoring baseline ls published and the budget target is understood draft legislation will begin to emerge that look to reform a few specific areas of the farm bill while leaving most of the remainder unchanged from existing laws. These proposed changes will have budget implications – if spending is increased from a change an offsetting change in some other area of the farm bill must be proposed. This process of putting together changes may be done with input from outside interests or agencies within the government whose funding and priorities are impacted by the farm bill.

Eventually, relevant committees in the House and Senate will begin their work proper — collecting ideas from draft legislation, executive agencies, the White House, think tanks, lobbies and any number of other sources that participate as stakeholders in the process. Committee version of bills are those that will eventually be “passed out of committee” for full votes on the floor of the respective body. These bills are fully articulated forms of new farm legislation, renewing or replacing existing law and identifying the mandated parameters and authorities for nutrition, commodity support, conservation, rural development, and other areas folded into the omnibus bill.

Navigating the political landscape to final passage

For the incoming Congress of 2023, the Senate and House will have majorities from different parties meaning that the versions of farm bills moving out of committees for floor votes are expected to be quite different. The political landscape for 2023 bears many similarities to what we saw in the period leading to the 2014 Farm Bill. At that time, the previous three years had seen a number of large spending relief bills to manage the financial crisis and recession of 2008 and Republicans took over the House of Representatives’ majority with reducing government spending as a key plank of the agenda. The federal government makeup – with Senate and Presidency held by Democrats and the Republican majority in the House of Representatives is identical in 2023 to the that seen in 2008 as indicated in Table 1.

In 2008, the Nutrition title of the Farm Bill was one of a number of areas targeted for government spending cuts and eventually the House of Representatives passed legislation that would have split farm income and nutrition support programs into separate bills. This process stretched out over more than two years with the 2008 Farm Bill being allowed to expire in 2012. Extensions of the 2008 law in 2012 and then again in 2013 preserved the rules of the 2008 farm bill while work continued to find common ground on a new five-year Farm Bill.

Ultimately, the 113th Congress was able to get close enough bills in each chamber to assemble a conference of Senators and Representatives from both parties to reconcile the different versions of farm legislation. The process of going to “conference” to negotiate a combined form of the legislation is typical for farm bills. The conferees are appointed by leadership of both parties in each chamber and are tasked with finding a compromise bill to send back to each chamber for a final vote. From there, the legislation moves to the President for signature or veto.

Enacting the farm bill

Once a farm bill (or any law) is passed executive branch agencies are charged with implementing the specific rules and regulations that are consistent with the legislation. The United Stated Department of Agriculture is largely charged with preparing the rules for farm and nutrition support programs – including setting the guidelines and schedules for enrollment, eligibility, and payment receipts. It is when these rules are written that government and other institutions will begin providing tools and education materials to assist stakeholders with understanding their rights and responsibilities as defined by the farm bill, including their process for claiming any qualifying entitlement payments.

For mandatory spending programs (e.g., commodity support payments, SNAP benefits) USDA implementing the payment process finalizes the process for the life of the farm bill. This is in contrast to the many discretionary programs (e.g., some research or rural development initiatives) where the Farm Bill authorizes program functions but does not allocate a budget – leaving the funding of those programs to the annual appropriations process where Congress sets USDA’s operating and program budget for non-mandatory programs.

Farm Bill 2023 possibilities

Having reviewed the steps required to produce new farm legislation, it is reasonable to ask how that process might proceed in the current politico-economic environment and whether it is likely to be successfully completed during Fiscal Year 2023. The closest setting for 2023 is the failed farm bill effort of 2012 which featured a Republican run Congress that took control in a midterm election of a first term Democrat presidency. The US House has 74 new members in 2023 and the 2012 Congress featured 89 newly elected members from the 2010 election – both significantly more than the prior election year turnover.

The economic climate – while quite different in terms of the origin and effects in 2011 and 2012 – is similarly uncertain in 2023 following the pandemic. In both 2012 and 2023, growing deficits have been driven by stimulus spending in response to economic shocks and that spending brings light on mandatory program spending like that of the Farm Bill. The nutrition title as the largest spending in the Farm Bill and the one that increases most readily as the economy worsens will be the biggest point of contention and the one most likely to stall out the legislative process and lead to an extension of the 2018 Farm Bill.

An unlikely outcome but one that might do the most to quell uncertainty is an early extension of the farm bill for one year. A priority of agricultural interests in the farm bill in many areas is simply that the farm bill is maintained – especially the crop insurance title[3]. Working simultaneously on an agenda that replaces current farm legislation in 2024 while establishing the 2024 crop year as being governed by an extended 2018 Farm Bill would contribute valuable policy certainty to an agricultural economy and allow time to consider a possible expanded role for the farm bill in a number of agricultural policy interests such as immigration or trade.

Tables & Figures

Table 1. Reviewing political landscape of recent Farm Bills

| Year | Congress | Presidency | Senate | House |

| 2008 | 110th | Republican | Democrat | Democrat |

| 2014 | 113th | Democrat | Democrat | Republican |

| 2018 | 115th | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| 2023 | 118th | Democrat | Democrat | Republican |

Table 2. Summary information on recent Farm Bill processes

| Year | Identifier | Title | House Vote | Senate Vote |

| 2008 | H.R.2419 | Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 | 316-108 | 82-13 |

| 2014 | H.R.2642 | Agricultural Act of 2014 | 251-166 | 68-32 |

| 2018 | H.R.2 | Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 | 369-47 | 87-13 |

Note: The 2008 Farm Bill vote listed is the tally from the veto override. The bill was sent to the President with a vote of 318-106 (House) and 81-15 (Senate).

Figure 1. Table of contents example from May 2022 CBO farm bill baseline. Source: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2022-05/51317-2022-05-usda.pdf

Figure 2. Example (partial) table from Mat 2022 CBO baseline – PLC feed grains payments

[1] The May 2022 CBO baseline is the most recent at the time of this writing.

[2] A positive score is one where spending increases while a negative score indicates projected reduction in government outlay.

[3] Crop insurance is established by permanent law outside of the Farm Bill so an expiring farm bill does not impact the permanent authority of crop insurance policies. However, the crop insurance program parameters would revert back to those set in permanent law and would require some legislative fix either as a standalone bill or attached to some other legislation.