What is the “language” of the farm bill?

January 26, 2023

PAER-2023-10

Roman Keeney, Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics

Many economic policy discussions develop a language of their own and the farm bill is no exception. As discussion of new farm legislation to replace the expiring 2018 Farm Bill moves forward it is useful to take stock of some key terms, concepts, and descriptors that make up the “language”[1] of farm bill debate. This terminology can be usefully split into categories: common legislative descriptors, Farm Bill specific verbiage, and the terminology adapted from economics for discussion of potential impacts and outcomes. We take each of these in turn and close the brief discussion of specifics for the 2023 Farm Bill debate.

Legislative process descriptors

There are a host of terms commonly used in discussing the legislative process. A bill is a congressional action, proposed for passage by the full Congress and requiring the president’s signature or a congressional supermajority overriding a veto to become law. A bill that becomes law will then be put into effect by appropriate federal agencies. This is sometimes referenced as the rules process where a federal agency writes the specific rules and regulations for carrying out Congress’ directions as enacted. The federal register of laws is then amended if those rules are passed.

The Farm Bill is a spending bill[2] because it authorizes disbursements from an authorized agency such as the Social Security Administration or in the case of many Farm Bill commodity programs the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). Spending bills face additional rules in Congress, notably the “pay as you go” (PAYGO) rule that requires such bills to find offsetting reductions for any spending increases. The PAYGO rule is related to the process of budget scoring. Budget scoring is the process where the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates all of the spending changes going forward compared to a status quo spending amount, referred to as the baseline. A positive budget score represents an estimated increase in total spending while a negative budget score represents the opposite.

The baseline estimate for the Farm Bill is calculated over a ten-year horizon using government forecasts on prices, outputs, productivity and other factors. During a year in which the Farm Bill is being replaced with proposed legislation, the CBO baseline becomes the spending estimate used for scoring all proposed changes in mandatory spending items in the farm bill. A mandatory spending program is one where Congress has already authorized the disbursement of funds. These are often called entitlements because the legislative language itself indicates that anyone meeting the qualifications described in the law is “entitled” to a payment calculated using whatever formulae have been approved for determining the qualifying amount.

The PAYGO rule on budgeting applies only to the budgeting process used to pass the legislation. Once the law is in effect mandatory spending items are authorized and these entitlements are paid in full whether the calculated amounts cause farm bill spending to increase or decrease relative to the baseline amounts used during passage. This means that the Farm Bill baseline is adjusting over time based on estimated economic conditions. The alternative to mandatory programs is a discretionary designation. Discretionary programs are authorized in the farm bill, but their funding is not – making them subject to the annual appropriations efforts.

Of final legislative term that defines farm bills is the incorporation of a sunset provision that sets an end date for the authority established in the law. Modern farm bills are thus not permanent law because they incorporate these sunset provisions that expire authority. Many farm programs in the farm bill are amendments or replacements to pre-existing permanent law and the expiration of a farm bill causes reversion to the specifics of those permanent laws. In the case of agriculture’s commodity programs, the reversion process returns commodity support to a set of programs established more than 70 years ago that are no longer feasible for implementation.

Farm Bill verbiage

The terms highlighted in the preceding section are general to the legislative process. Beyond the normal terminology used in discussion of congressional policymaking there are some specifics to the farm bill that are key to fluency in discussion of agricultural policy. Farm bill programs are administered by agencies of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) with the Secretary of Agriculture being the administrative and political head of that department. USDA is charged with writing the specific rules for implementing a farm bill based on the authorizations and intentions of Congress.

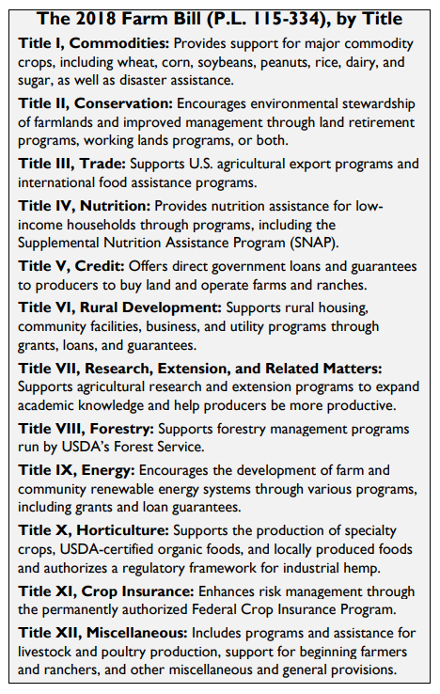

The farm bill is divided into titles representing the different core policy areas. The farm bill is an example of omnibus legislation, a large package of related government programs that are bundled together and negotiated with the intention of passing them as a block. The history of the farm bill has seen several program areas added to the block package. Most prominently, some 50 years ago a number of programs offering food assistance to low-income households from the “war on poverty” era of 1960s policy were incorporated into the farm bill into what we now know as the nutrition title. Subsequent farm bills have expanded scope as policy areas relevant to agriculture have warranted such action resulting in the addition of conservation, crop insurance, trade and energy titles among others (see figure 1).

There are many programs in the farm bill and many of them are best known by their acronyms. The Title I commodity programs are focused on commodity and income support for agriculture. Most prominent among these are the price loss coverage (PLC) and agricultural risk coverage (ARC) programs that allow producers to enroll their base acres. Base acres are a representation of historical[3] commodity allocation on the farm tied to a designated reference period. Base acres are distinct from actual allocation of crops to farm acres meaning that current planting decisions do not impact the eligibility for payments. The PLC and ARC programs are intended as shallow loss programs, to provide small amounts of income support that assist with losses that are not covered by typical crop insurance coverage contracts. Crop insurance is established in its own permanent law and is not part of the commodity title. The crop insurance title (Title XI in 2018’s Farm Bill) of the farm bill amends crop insurance programs to update a number of parameters of that program.

Figure 1. Description of titles from the 2018 Farm Bill, Reprinted from CRS Publication IF 12047.

In addition to PLC and ARC additional commodity support is available tied to the loan rates that set price floors for commodities and can be used through the marketing assistance loan program (MAL) or can trigger loan deficiency payments (LDP). Eligibility for support in the loan rate, shallow loss, and crop insurance subsidy programs may require some degree of conservation cross compliance with mandatory conservation practices reported to USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) and Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) for a particular set of land attributes. In addition to compliance rules the farm bill incorporates a conservation title (Title II) that establishes land retirement programs like the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) which take land out of production for a contract period in exchange for a rental payment.

The role of commodity support and conservation programs in the farm bill draw significant attention for their role in decision-making on farms, but these programs only account for 15-25% of total government spending at any time. The nutrition title (Title IV) comprises most of the spending of the farm bill via the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and other initiatives that supplement food budgets for low income households.

The nutrition title is the most politically contentious component of the farm bill, but subsidies to both farms for income support and households for their food purchases are frequently cited for inefficiencies and creating dependencies on government support. As such, debate about both types of programs frequently turns to some form of means testing[4] – measures to target recipients of support to those most in need. Additionally, payment limits are in place for many of the farm and food subsidies in the farm bill as a means of controlling total spending and the amount any individual or household might receive in government support.

Economic policy discussion

With some basics of the policy structure in hand, we are ready to turn to items often encountered when the economic costs and benefits of the farm bill are discussed. We will take a little more space to elaborate definitions and provide examples here, as these represent the concepts and terms that are most dependent on a complete understanding of economic principles.

The economist’s perspective on policy often begins from a notion of equilibrium – a balancing of supply and demand forces that lead to a prevailing price and quantity exchanged in a market. The common convention is that of free market equilibrium where there is no intervening force introduced between that of supply and demand such as a government subsidy or tax. Once a tax or subsidy is introduced, there will be a change from the price and quantity of free market equilibrium and these changes are referred to as economic distortion. These distortions come with costs to efficiency which is the grounds economists typically use in fundamental critiques of levels tax and subsidy use.

The story goes deeper. Economic policy analysis will often accept that a goal is to move away from the prevailing equilibrium quantity and price to one that generates some public benefit or policy objective – such as stabilizing farm income or increasing the food budgets of poor households. The incidence of a policy is a common economics term for measuring the impact of these policies to estimate how the intervention effects are spread between different participants in a market. For example, if a subsidy is attached to a farm gate price of a product the analysis of incidence would focus on how much of the subsidy becomes increased price received by the farmer versus how much of the subsidy shows up as benefits in other places in the value chain.

In addition to distortion and incidence, economists also frequently classify tax or subsidy policies as direct or indirect. A direct subsidy is one where the farmer receives the cash value of the subsidy in form of a payment. An indirect subsidy is one where the farmer does not receive the value as payment but benefits from the intervention in the terms of a higher (for output) or lower (for inputs) price in a transaction. Direct subsidies to farmers are those payments such as PLC benefits which change the revenue from operations. An indirect subsidy might occur when for example a famer pays a lower price for input because some automatic rebate is applied at the point of sale. It is important to note that in the analysis of the economics the difference between a direct and indirect subsidy should be minimal. The choice between the two in the policy process is usually driven by the most manageable form of implementation.

The two terms that most distinguish economics in discussion of policies like the farm bill from everyday language are welfare and capitalization. Both arise from the previous notions of incidence and distortion. Welfare has a common usage as a catchall term for low-income assistance programs but in economics it is a term used for the measurement of well-being. When a welfare measure is cited in economic analysis, it is typically reported as a change in well-being that arises from comparison of activity with and without some policy in place.

For example, if a proposed policy change indicated a reduction in the support rate for crop insurance contracts traditional economic analysis would require establishing the status quo measure (well-being under the normal policy) and compare it to an estimate under the alternative (well-being with reduced support). It is important to note that these measured welfare changes can be quite different from the change in government spending for crop insurance support. The welfare change would consider all responses the farmer makes when the support rate is lowered as we would expect the reduced support to affect several decisions made by the farmer.

A final term of importance for those delving into the economics dimension of the farm bill is capitalization. There is a long history of measuring how government support policies in agriculture influence asset prices, particularly land. Because land is fixed in supply and location, it represents a factor in the economy with minimal adjustment. In the previous paragraph, we noted that a changes to crop insurance support could trigger a number of farm level adjustments, but land’s fixedness means that its use in crop production likely to hold relatively constant. Longstanding economic equilibrium analysis indicates that a relatively fixed input like land is more likely to capture the effects of policy in its value. Historically, the transfer of farm subsidy values into higher land purchase or rental prices have come to be known as “capitalization” as a shorthand term. Different policies will have different linkages to land as a fixed input and different expected capitalization rates and have continually been an important component of understanding how policies play out at the farm and land-owner level in agriculture. Both welfare and capitalization become important concepts because they are measures aimed at understanding and describing the full of a policy beyond those that show up only as changes in the amount of government spending.

Concluding comments

The aim of this brief has been to help readers navigate the 2023 farm bill debate as they encounter it through media, political commentary, and contributions from economic analysis. The material in this brief is not exhaustive but gives a useful primer for those trying to track farm bill progress and form their own views about that process.

Additional resources on this topic

Congressional Research Service – Preparing for the next farm bill

Economic Research Service USDA – Farm and commodity policy

[1] The use of “language” here is not intended as a reference to the legalese language used in the farm bill as an act of congress.

[2] Spending bill is often used as a synonym for the combined appropriations bills that fund the government annually. But the farm bill (and others) may authorize spending rules over a longer time horizon – like the five-year length of the typical farm bill.

[3] The use of historical planting in determination of basis is a mechanism to “decouple” the farm’s entitlement payment from current decision-making. We discuss decoupling in the section on the economic terminology of farm policy.

[4] For general discussion of SNAP limits see https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/recipient/eligibility, though rules vary state by state. Farm payment limits are set by federal rule and are dependent on several eligibility factors in terms of ownership interest and engagement in farm activities.