Orphan Crops and the Success of Quinoa

Hannah Levengood - PhD Candidate

In today’s world, techniques of food cultivation have become a crucial element in supporting many aspects of our daily lives. Whether it’s locally grown harvests or internationally grown foods, we find ourselves eating these crops nearly every day. In fact, over 90 percent of global nutrition comes from just 15 plant species. While more than 50,000 edible plants exist across the world, only a small fraction of these are commercially cultivated for food. Among these 15 central crops, wheat, rice, and corn alone account for half of the global food supply. This heavy reliance on a few plants places growing pressure on farmers to maximize their production. This is a problem. Not only because it is becoming increasingly difficult to meet demand, but many high yielding plants have the unfortunate drawback of trading quantity for quality- resulting in crops that have much less nutrients than their lower yielding counterparts.

So how do we meet the demands of a growing global population, while also making sure our food contains the necessary nutrients that we need? The answer may lie in a special classification of plants called orphan crops. The best way to illustrate what orphan crops are is through the example of homegrown tomatoes. Anyone who has eaten a tomato from their own garden will likely agree that they are far more flavorful from what you would typically find at the grocery store. When gardeners want to save seeds to plant next year, they would not save seeds from tomatoes that lacked flavor. Instead, they would want to choose the best tasting ones in their garden so they continue to produce flavorful vegetables the next year.

This is how many ‘orphan crops’ have been cultivated; not for yield, but for their excellent flavor and adaptability to local regions. As a result, these crops are often richer in nutrients and are excellent candidates for improving global diets. By focusing on these crops and sharing them with the rest of the world, scientists believe that orphan crops could have a large impact on preventing hunger. One success story is Quinoa.

Traditionally grown in the Andes Mountains of South America, quinoa has been endorsed by the United Nations as a tool in the fight against global hunger. Yet until recently, quinoa cultivation has been confined to a narrow climate range, which severely limits its application in the real world. For scientists, the challenge lies in creating new varieties which can be adapted to any region and farming system globally, while also preserving its nutrition.

Genetic engineering of these orphan crops is the key to a widespread solution. While traditional breeding techniques have been instrumental in shaping the crops we eat today, they often come with the cost of reducing the very nutrients that make quinoa valuable. Additionally, modern crops were developed through centuries of breeding, but the urgency of addressing global hunger means that we cannot afford to wait that long for quinoa improvement. By using genetic engineering combined with gene editing, scientists can offer a solution far faster than those of modern crops. The precision given by gene editing means that only the traits that we want to change, such as the ability for quinoa to grow in different climates or producing shorter plants which are easier to harvest, without sacrificing any other traits. However, before we can do that, we first must determine exactly how quinoa can be modified, which brings us to the focus of my research.

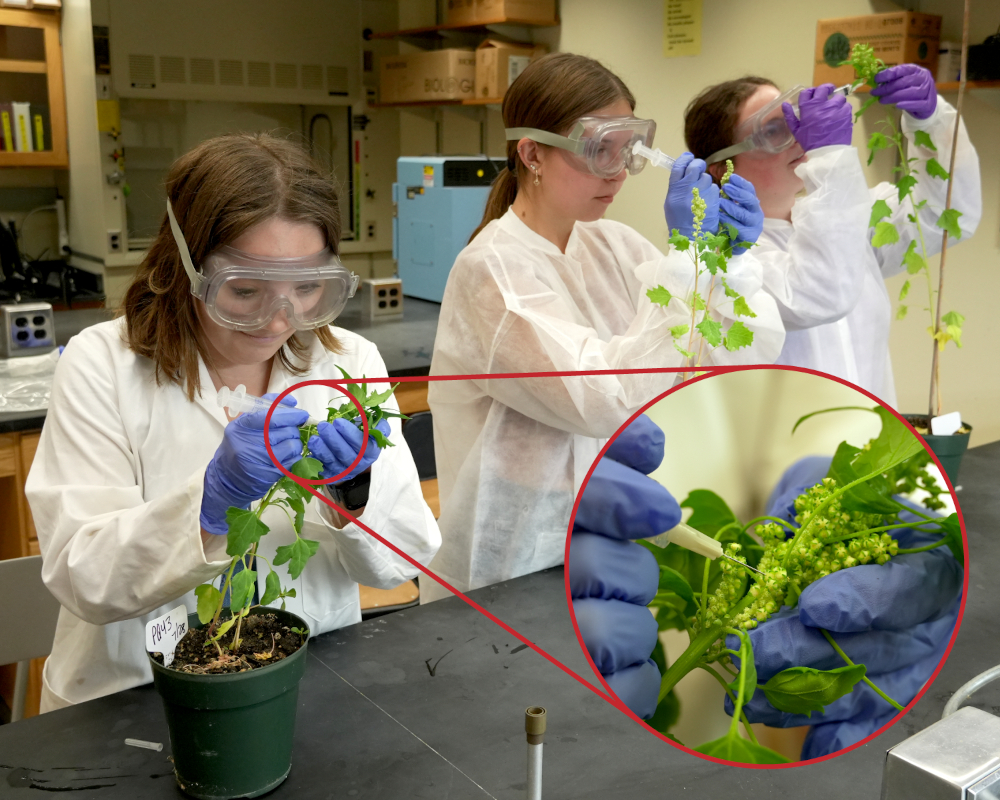

Despite their appearance in mainstream media, plants are hard to genetically modify. As all plants are different, this means that a new experiment needs to be designed for any successful modification to occur. Since quinoa research is relatively new, this means that we are basically starting from scratch when designing this research. Our research has focused on developing tools that make it easier to genetically modify this plant. This includes establishing methods to grow it in a sterile environment, optimizing tissue culture for cloning, and identifying the best strain of Agrobacterium- the organism responsible for making genetic changes in both gene editing and genetic engineering.

While we have yet to successfully produce a modified quinoa plant, our research has revealed important insights that will be helpful in establishing its genetic development. We can modify the genes of individual cells, signaling that the problem is not in making genetic changes, but rather with developing these cells into whole plants. We have also found that quinoa varieties respond differently to the hormones of tissue culture and the Agrobacterium, suggesting that genetic engineering may need to be tailored to each variety to be successful.

These findings mark important first steps toward enabling genetic improvement of quinoa- work that could help transform it from a regional orphan crop into a global instrument in the fight against hunger.