Conservation Initiatives

Hellbenders have been rapidly declining since the 1980s due to various factors, including poor water quality, loss of habitat, and diseases like chytrid fungus and ranavirus. Populations are so low that they cannot rebound on their own, and require our help. Conservation efforts include captive breeding and rearing in order to head start populations and increase survivorship. Thankfully, zoos and universities across the country are working together to establish and grow these programs. More information about each of these programs can be found in the conservation efforts drop down menu.

For information on what you can do to help the hellbender, please visit the "What Can You Do" web page. Find out how you can adopt hellbender friendly practices that improve water quality.

Protect the Giant Salamander — your gift makes a difference!

Research Helping Hellbenders

Captive rearing of hellbenders is a strategy used in hellbender conservation efforts as a way of increasing the survival rate of young hellbenders. The hellbender population has decreased by 77% since the 1980s, with habitat loss and water quality being the main causes of their decline. Survival is especially low in young hellbenders, with many dying before they reach sexual maturity or adulthood.

Captive rearing of hellbenders is a strategy used in hellbender conservation efforts as a way of increasing the survival rate of young hellbenders. The hellbender population has decreased by 77% since the 1980s, with habitat loss and water quality being the main causes of their decline. Survival is especially low in young hellbenders, with many dying before they reach sexual maturity or adulthood.

Universities and zoos across the country participate in these captive-rearing programs. Eggs are collected from rivers where adult hellbenders spawn, with each female laying 200-400 eggs. The eggs are kept in climate-controlled rooms with continuous water flow. After 72 days, the eggs hatch into larvae that still retain their yolk sac for the first few months.  After 1.5 years, the hellbender larvae lose their external gills and more closely resemble an adult hellbender. Hellbenders reach adulthood at 5 to 8 years, at which point they are released back into the wild in suitable habitats.

After 1.5 years, the hellbender larvae lose their external gills and more closely resemble an adult hellbender. Hellbenders reach adulthood at 5 to 8 years, at which point they are released back into the wild in suitable habitats.

As an amphibian, hellbenders are R-selected breeders, meaning they lay a large number of eggs and only a small portion of those survive to adulthood. Male hellbenders will guard the eggs until they hatch (pictured to the left), but the hellbenders will not reach adulthood until they are 5 to 8 years old. This long life cycle results in many larval hellbenders being unable to survive to adulthood, especially with additional environmental stressors like poor water quality and predation by fish. This is where captive rearing becomes especially useful, as hellbenders are raised in controlled environments until they reach adulthood. However, captive rearing comes with its own challenges.

As an amphibian, hellbenders are R-selected breeders, meaning they lay a large number of eggs and only a small portion of those survive to adulthood. Male hellbenders will guard the eggs until they hatch (pictured to the left), but the hellbenders will not reach adulthood until they are 5 to 8 years old. This long life cycle results in many larval hellbenders being unable to survive to adulthood, especially with additional environmental stressors like poor water quality and predation by fish. This is where captive rearing becomes especially useful, as hellbenders are raised in controlled environments until they reach adulthood. However, captive rearing comes with its own challenges.

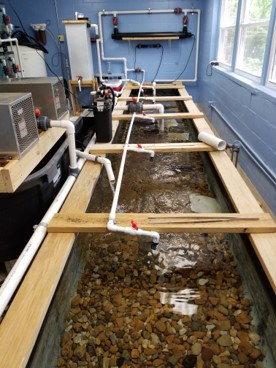

Recreating Hellbender Habitat: Hellbenders require cold, clean, fast flowing water similar to that which is found in the wild.  Eggs are kept in tanks where water flow is continuous in order to prevent disease transmission between eggs. Tanks are also kept in rooms at about 15 degrees Celsius. Hellbenders are also provided with cover in the form of large rocks and tunnels in order to recreate the large rocks they typically hide under in the wild, similar to those pictured on the right. Hellbenders are fed crayfish, which is their primary food source in the wild.

Eggs are kept in tanks where water flow is continuous in order to prevent disease transmission between eggs. Tanks are also kept in rooms at about 15 degrees Celsius. Hellbenders are also provided with cover in the form of large rocks and tunnels in order to recreate the large rocks they typically hide under in the wild, similar to those pictured on the right. Hellbenders are fed crayfish, which is their primary food source in the wild.

Reintroduction into the Wild: Despite being raised in captivity, released hellbenders will still face some challenges when being reintroduced. They will have to scout out good locations for feeding and resting and develop their own home range. A river is quite different from a tank in a lab, with environmental changes like temperatures changes and weather, competition for food, water currents, and predation all being new introduced conditions.  Research is being conducted in order to stimulate these conditions in captivity and increase survival after release.

Research is being conducted in order to stimulate these conditions in captivity and increase survival after release.

Captive rearing of hellbenders is a strategy used in hellbender conservation efforts as a way of increasing the survival rate of young hellbenders. The hellbender population has decreased by 77% since the 1980s, with habitat loss and water quality being the main causes of their decline. Survival is especially low in young hellbenders, with many dying before they reach sexual maturity or adulthood.

Captive rearing of hellbenders is a strategy used in hellbender conservation efforts as a way of increasing the survival rate of young hellbenders. The hellbender population has decreased by 77% since the 1980s, with habitat loss and water quality being the main causes of their decline. Survival is especially low in young hellbenders, with many dying before they reach sexual maturity or adulthood.

Universities and zoos across the country participate in these captive-rearing programs. Eggs are collected from rivers where adult hellbenders spawn, with each female laying 200-400 eggs. The eggs are kept in climate-controlled rooms with continuous water flow. After 72 days, the eggs hatch into larvae that still retain their yolk sac for the first few months.  After 1.5 years, the hellbender larvae lose their external gills and more closely resemble an adult hellbender. Hellbenders reach adulthood at 5 to 8 years, at which point they are released back into the wild in suitable habitats.

After 1.5 years, the hellbender larvae lose their external gills and more closely resemble an adult hellbender. Hellbenders reach adulthood at 5 to 8 years, at which point they are released back into the wild in suitable habitats.

As an amphibian, hellbenders are R-selected breeders, meaning they lay a large number of eggs and only a small portion of those survive to adulthood. Male hellbenders will guard the eggs until they hatch (pictured to the left), but the hellbenders will not reach adulthood until they are 5 to 8 years old. This long life cycle results in many larval hellbenders being unable to survive to adulthood, especially with additional environmental stressors like poor water quality and predation by fish. This is where captive rearing becomes especially useful, as hellbenders are raised in controlled environments until they reach adulthood. However, captive rearing comes with its own challenges.

As an amphibian, hellbenders are R-selected breeders, meaning they lay a large number of eggs and only a small portion of those survive to adulthood. Male hellbenders will guard the eggs until they hatch (pictured to the left), but the hellbenders will not reach adulthood until they are 5 to 8 years old. This long life cycle results in many larval hellbenders being unable to survive to adulthood, especially with additional environmental stressors like poor water quality and predation by fish. This is where captive rearing becomes especially useful, as hellbenders are raised in controlled environments until they reach adulthood. However, captive rearing comes with its own challenges.

Recreating Hellbender Habitat: Hellbenders require cold, clean, fast flowing water similar to that which is found in the wild.  Eggs are kept in tanks where water flow is continuous in order to prevent disease transmission between eggs. Tanks are also kept in rooms at about 15 degrees Celsius. Hellbenders are also provided with cover in the form of large rocks and tunnels in order to recreate the large rocks they typically hide under in the wild, similar to those pictured on the right. Hellbenders are fed crayfish, which is their primary food source in the wild.

Eggs are kept in tanks where water flow is continuous in order to prevent disease transmission between eggs. Tanks are also kept in rooms at about 15 degrees Celsius. Hellbenders are also provided with cover in the form of large rocks and tunnels in order to recreate the large rocks they typically hide under in the wild, similar to those pictured on the right. Hellbenders are fed crayfish, which is their primary food source in the wild.

Reintroduction into the Wild: Despite being raised in captivity, released hellbenders will still face some challenges when being reintroduced. They will have to scout out good locations for feeding and resting and develop their own home range. A river is quite different from a tank in a lab, with environmental changes like temperatures changes and weather, competition for food, water currents, and predation all being new introduced conditions.  Research is being conducted in order to stimulate these conditions in captivity and increase survival after release.

Research is being conducted in order to stimulate these conditions in captivity and increase survival after release.

Check out our Zoo Programs

Check out our Zoo Programs

Many zoos across the country have their own captive rearing or breeding programs for hellbenders. These zoos partner with universities in order to establish their own facilities for the hellbenders then receive a number of young hellbenders to rear. This partnership is incredibly beneficial as it allows zoos to participate in the conservation process and educate general public about the hellbender and its decline.

Some zoos also have their own captive breeding programs. The St. Louis zoo, for example, has 2 large, outdoor stream chambers that are 40 feet long and 6 feet deep as well as an indoor 32-foot simulated stream. Each simulated stream has rock and gravel cover as well as artificial nest boxes. Saint Louis had its first successful captive egg spawning in 2011, and now many zoos are working on establishing their own breeding programs.

Check out this free downloadable publication: How Our Zoos Help Hellbenders.

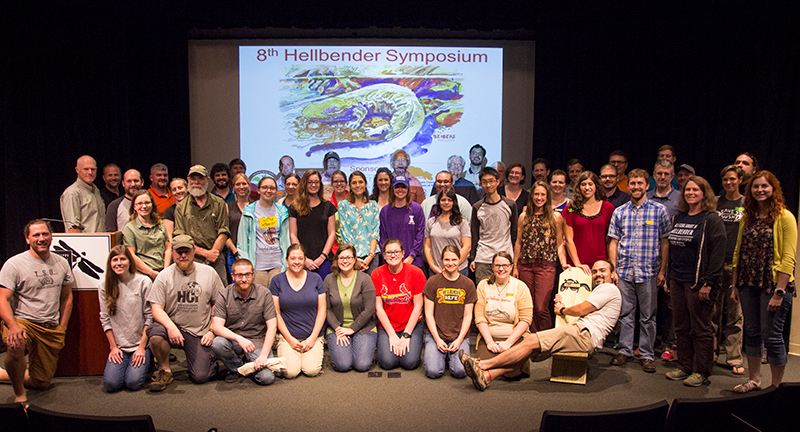

Hellbender Symposiums

Hellbender Symposiums bring together experts and communities to share research and conservation strategies. Want one near you? Contact us to learn more!

Funding For Farmers Helping Hellbenders

Funding is now available to producers in the Blue River-Sinking Watershed to implement conservation practices on their land to assist with the recovery of Eastern Hellbenders and improvement of aquatic resources. This funding is provided through USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS) Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP).

Learn moreHellbender News

Hellbender Research Publications

Learn moreHellbender Research Publications

Learn more