Launching Technology from Discovery to Delivery

When David Wilson visited farmers in Ethiopia last fall, he watched oxen trample grain to remove the chaff. Months earlier, those same oxen slowly pulled moldboard plows through a field before the crop was planted.

For those farmers, crop loss can be significant, as grain laid in the sun to dry and then threshed by stomping animals can blow away or become contaminated by those animals, dust, or insects. Later, when taking the grain to market, rutted, sometimes muddy roads make vehicle transportation difficult. Farmers tend to walk, carrying only what they can haul by hand.

The farmers Wilson has met in Ethiopia, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Kenya aren’t likely to see their roads paved. And the tools farmers in more developed countries use to mechanize plowing, harvesting, drying, and threshing are simply too expensive for these growers, who are mostly subsistence farmers, with little left over to sell.

College of Agriculture researchers have been working on problems like these for years, and the affordable, multiuse tools they’ve developed could quickly make an impact where they are needed most. But many large companies aren’t interested in investments that aren’t likely to provide a quick or abundant return. Rather than let their work languish on a shelf, Purdue researchers are taking on the challenges of entrepreneurship.

“To see the farmers actually spending hours and hours manually working on these things—and losing half their yield— showed me the importance of this type of work,” Wilson says. “Universities do well at research and development, and there are examples of successful implementation of technology. This needed to get to the farmers, and it just couldn’t wait.”

Wilson (BS ’13, MS ’15, agricultural and biological engineering) and several current and former students founded Mobile Agricultural Power Solutions (MAPS) to produce a versatile basic utility vehicle that can be used on sub-Saharan farms to haul water and crop inputs, plow fields, and haul as much as 1 ton of yield to market on even the worst roads.

And Klein Ileleji, an associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering, started JUA Technologies with his wife, Reiko Habuto Ileleji (MS ’01, PhD ’08, education) to further develop and market a multifunctional device that can dry grains and horticultural food crops and run small household appliances.

Both companies are now working to enter markets where the technologies are needed most. These activities must be separate from work conducted for University appointments, so startups are often championed by a student or other person close to the work developing the commercial operation, with a faculty member contributing to related research and learning about entrepreneurship. Startups must also compensate Purdue at fair market rates for any University resources used.

the takeaway

- President Mitch Daniels has made research commercialization a key initiative of his Purdue Moves—and College of Agriculture faculty, staff, students, and alumni are taking advantage of resources like the Purdue Foundry and the Ag-celerator fund to take their innovations to market.

- Commercial channels can allow for more efficient dissemination of knowledge and technology at a wider scale, says Dan Dawes a College of Agriculture alumnus and entrepreneur-in-residence at the Purdue Foundry.

- Recent innovations in the College include a multipurpose grain dryer; software to predict grain yield and optimum fertilizer applications; a faster, cheaper method for E. coli detection in food products; and a utility vehicle that can be sourced, built, and used in sub-Saharan Africa.

Encouraging Purdue entrepreneurs

Ileleji, through many research visits to Nigeria and Ghana, saw the need for an inexpensive drying technology to reduce grain losses and joined a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Food Processing Innovation Lab team led by Purdue to develop a multipurpose solar crop dehydrator. It not only dries crops, but also acts as a generator, supplying power to homes and small electronic devices while in the field.

Klein Ileleji, associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering, displays his prototype for a solar-powered crop dryer that also works as a generator for small appliances. It was designed to improve drying efficiency by enabling high temperatures, high air-flow rate, and low humidity. The name of the startup he co-founded, JUA Technologies, comes from the Kiswahili word jua, meaning "sun."

As with Wilson’s utility vehicle, most companies balked at investing in technology marketed to some of the poorest farmers on the continent. “Companies are not going to go into this market, because it is not attractive. You can’t convince the large guys, since the money is not there to show for it,” Ileleji says. “If you compare what companies in the West invest in developing tech for agriculture versus what is invested in Africa, it’s very abysmal.”

So Ileleji joined the growing ranks of agricultural entrepreneurs at Purdue, scouting opportunities for manufacturing and sales in his time allotted for Jua Technologies, starting in Kenya and Senegal, the site of the USAID project. He is also pursuing market opportunities with small fruit and vegetable farmers in the United States, who are interested in dehydrating their harvests, and recently won a USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture grant to do so.

JUA Technologies has benefited from Purdue President Mitch Daniels’ push for commercialization of Purdue research. Ileleji took advantage of resources at the Purdue Foundry, an entrepreneurship hub developed through the Purdue Research Foundation (PRF) and dedicated to moving student, faculty, and alumni ideas more quickly to the marketplace.

Dan Dawes (BS ’80, agricultural economics), an entrepreneur in residence at the Foundry who focuses on mentoring agriculture startups, says there were about eight startup companies born at Purdue each year. Following the launch of the Foundry and amended processes in the Office of Technology Commercialization, that number tripled.

“If you look at Purdue’s mission, it speaks to serving the citizens of Indiana, the United States, and the world through discovery, and through the dissemination of knowledge and the preservation of knowledge,” Dawes says. “Commercialization of good ideas and technology is the most efficient way for that knowledge to be more broadly disseminated.”

Keeping manufacturing local

The MAPS utility vehicle was born from a team led by John Lumkes, associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering, who led trips to Cameroon over several years. The team designed seven prototype vehicles for farm transportation in partnership with the African Center for Renewable Energy and Sustainable Technology, which now has three vehicles for daily use or to rent to local farmers.

Alumnus David Wilson drives the AgRover, a utility vehicle designed to maximize productivity while remaining affordable in developing regions of the world. Local manufacturing using local parts and materials also makes the vehicles easier to maintain.

From a wooden prototype in 2012 to today’s AgRover—a metal-frame, three-wheel vehicle that can act as a tractor or carry a one-ton payload—the company’s founders believe they have an affordable product that can improve the livelihoods of sub-Saharan farmers. Local technicians are currently fabricating the vehicles in one Nigerian workshop, and Wilson hopes to eventually launch production and sales in other African countries as well.

Some farms benefit from subsidized or donated farm machinery, but when those vehicles break down, spare parts are costly to import, and farmers may not have the skills to fix them.

The AgRover solves those problems. “It’s cheaper than importing a tractor. It’s more flexible in its use than trucks that are on the market and imported,” Wilson says. “Every single part on the vehicle we purchased in Lagos [Nigeria]. If you need to replace that part, it’s there, and since it will be manufactured locally, the mechanical skills are also available.”

Wilson and his colleagues are gearing up to apply for grants, participate in Purdue Foundry activities, and take advantage of the resources available through Purdue to take their technology to market.

Champions for commercialization

Over the years, Philip Hess, an applications analyst programmer in the Department of Agronomy, and Brad Joern, a professor of agronomy, saw similar distribution challenges. The tools they develop help farmers estimate crop yield and apply fertilizers appropriately and economically. These tools can increase farmer profitability and improve the environmental sustainability of the industry.

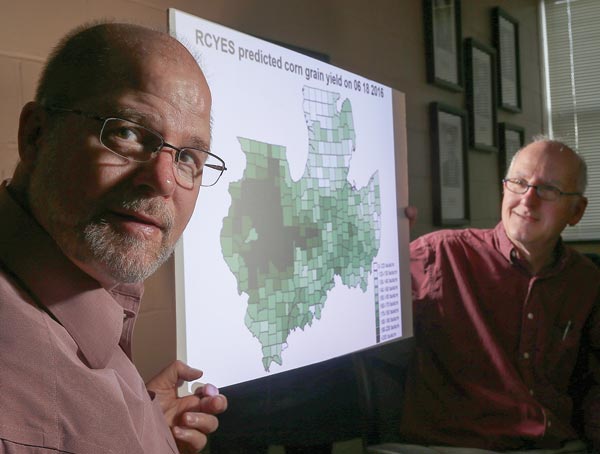

Brad Joern, professor of agronomy, and Philip Hess, applications analyst programmer, display predicted 2016 corn yields for the Midwest, using a map generated in mid-June 2016, well before yield data were available. The Regional Crop Yield Estimation System is one of the tools available from their startup, J&H Consulting.

“The amount of arable land on the planet isn’t going to increase. All we have left are efficiencies,” Hess says. “This is the latest way in which those efficiencies will be realized.”

Hess and Joern know that many growers look to agricultural companies—where they purchase seed, fertilizers, and crop protection chemicals— for information, either directly or through retailers and consultants. So they created J&H Consulting, which licenses these tools to agricultural companies to reach broader audiences.

“In the age of digital agriculture, a lot of the tools we develop are tools that can be best put to use in the commercial ag sector,” Joern says. “We wanted our tools to be as widely used as possible.”

Joern adds that developing the best tools for farmers isn’t enough. Getting them in the hands of end users is a difficult but important step. “That only happens if there is a champion behind the technology, and that is going to be the person who developed it,” he says.

Learning the ropes

Bruce Applegate, an associate professor of food science, developed a faster, cheaper method for detecting E. coli 0157:H7, a strain of the bacteria most commonly responsible for E. coli foodborne illnesses. Conventional tests require a lengthy enrichment process that multiplies scant amounts of E. coli bacteria into visible cells in a petri dish. His method employs a virus that infects the bacteria and causes them to glow, and can detect the bacteria early in the enrichment, saving valuable time. But as a scientist, he knew little about how to start or run a business, and he needed funding.

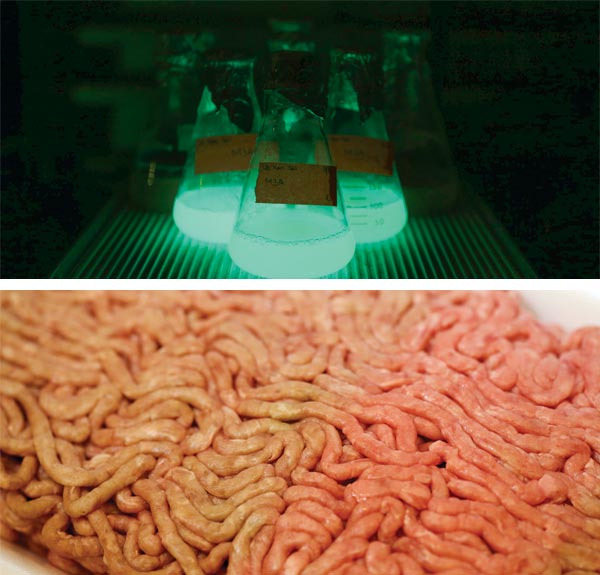

Bruce Applegate, associate professor of food science, developed a faster, cheaper method for detecting the bacterial strain most commonly responsible for E. coli foodborne illnesses. The NanoLuc virus infects the E. coli, causing it to glow in the dark when tested on food products like raw beef. (The media in the flask shown is a glowing surrogate for E. coli.)

Khashayar Farrokhzad (PhD ’14, biology), Applegate’s partner in the company and a former post-doctoral researcher in his lab, took part in the Foundry’s LaunchBox series, an entrepreneurship boot camp. Applegate attended the Entrepreneurial Leadership Academy, where he networked with other likeminded scientists working to put their ideas to use. Together, they founded Phicrobe.

“They helped get us going on how to put together a business plan. The Entrepreneurial Academy fellowship introduced me to people who had started companies before, and it gave me a lot of ideas,” Applegate says.

In January, Phicrobe was one of two agriculturalbased startups to receive an award from the inaugural Ag-celerator, a plant sciences innovation fund developed as part of the Purdue Moves plant sciences initiatives. The fund is operated by the Purdue Foundry with assistance from the College of Agriculture, Purdue Research Foundation’s Office of Technology Commercialization, and the agricultural industry. Phicrobe’s $75,000 award, along with other grants fostering the startup, have provided the opportunity to start lining up manufacturing capacity.

“Getting something into the industry that…is going to improve how we test for bacteria harmful to human health is really satisfying,” Applegate says.

Photos provided by Tom Campbell.