Using the Unused

Millions of dollars have been spent to stop the spread of invasive Asian carp throughout the Midwest’s rivers. The fish, introduced in the Southeast to control weeds and parasites in aquaculture, escaped decades ago into the Mississippi River and have been slowly making their way to the Great Lakes, where they threaten to outcompete native species and drastically change the ecosystem.

Electric barriers and dams have been built. Scientists have worked on developing a micro particle that would target and kill only Asian carp, and have tested to see if carbon dioxide or noise could drive them away. Still, an Asian carp was found in the Calumet River last summer, just nine miles from Lake Michigan, and rivers are teeming with the unwanted species.

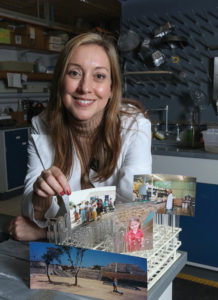

Volunteering in impoverished communities and working with local fishermen and indigenous communities during her undergraduate and graduate studies prompted Andrea Liceaga, associate professor of food science, to pursue a useful way to process carp meat.

That got Andrea Liceaga thinking. If the carp are here, what good can come from them? Her answer: chorizo. “I started digging out recipes for how to make chorizo with beef and pork, and I wanted to make it with fish, just substitute the protein,” says Liceaga, associate professor of food science.

Some businesses have had success making fish oil, fish meal or fertilizers from Asian carp. But the carp meat is high quality, and Liceaga found it wasteful not to use it for human consumption. Two major issues, however, have stopped people from putting Asian carp on menus across the Midwest.

First, people confuse Asian carp with the common carp, which is a bottom-feeder and can contain high levels of contaminants. The Asian carp species Liceaga works with — silver carp — is actually a filter feeder, taking in plankton that float through the water, so it doesn’t amass harmful levels of mercury or other problematic materials.

Second, Asian carp meat is full of small intramuscular bones like one might find in salmon, except that these are much more difficult to remove prior to cooking. But the grinding and processing done to make the chorizo separates the bones from the meat.

Initial formulations have received positive reviews from panelists who have tasted the chorizo, but there is still work to be done. Liceaga is working with visiting scholar Marco Trindade, associate professor of food engineering from the University of São Paulo in Brazil this spring. He’ll help optimize the formulation, work on food safety and preservation issues, and perfect processing techniques. Once that’s complete, Liceaga hopes to find a company interested in producing Asian carp chorizo for sale to the public.

Because she comes from a high-poverty part of Mexico, Liceaga looks for opportunities to utilize resources wisely. “When you really see poverty — people who are malnourished and living in poverty you can’t imagine — it leaves an impression that never goes away,” she says. “I can’t stand to see food being wasted.”

Liceaga also extracts carp proteins and modifies them for use as functional ingredients for the food industry, studying the fortification of staple foods with these proteins. She’s added Asian carp protein to corn tortillas that have gone over well in sensory tests.

fbotTrash or treasure?

Liceaga isn’t the only faculty member in the College of Agriculture converting the useless to something usable. Researchers are tackling local, regional and global problems in new ways.

Tamara Benjamin, assistant program leader and diversified agriculture specialist, had been brainstorming ways to get fresh fruits and vegetables into local food banks. The small amount of produce food banks do receive tends to come from local grocery stores that donate expired items or those past their prime, which patrons pass over.

Benjamin wasn’t sure how to address the problem until she picked up her community-supported agriculture basket from a local farm one day. The farmer had several thousand heads of romaine lettuce in the field without a buyer. Harvesting them would cost money without a guarantee of sale, so he planned to do what many in the situation do frequently — plow the crop under.

“There are farms out there that have excess food,” Benjamin says. “I thought, ‘Can we link those farmers who have a bumper crop to local food banks and solve both their problems?’”

That sparked the Waste Not, Want Not initiative, a network to connect food banks and local farmers who can negotiate prices when excess crops are available. The farmer might not get as much as he or she would selling to traditional buyers, but the deals cover costs and keep the food from going to waste.

“Supply chains like this aren’t well developed. Farmers can do this on their own for some things, but it’s a lot of extra work,” Benjamin says. “Waste Not, Want Not supports those farmers who need to find markets and those in need of food who want to connect with farms.”

The program is still in a pilot format, but it’s showing promise.

Adam Beck (BS ’01, agronomy, MS ’05 agricultural sciences education and communication), owner of Beck’s Family Farm in Attica, Indiana, often finds his farm has excess green beans. He’s donated them in some cases but has also used them as chicken feed. Now he has a contract to sell those beans to Food Finders in Lafayette.

“I’d much rather put green beans in people’s hands than feed them to the chickens,” Beck says. “With produce, if you don’t have an agreement in hand, you might be stuck with that amount of produce. Now I know if I plant five acres of green beans, all five acres are going to be used.”

At Food Finders, Executive Director Katy Bunder is excited about the possibility of offering clients more healthy, fresh options.

“Nothing compares to produce that is grown locally and is picked when it’s ripe and ready to eat,” she says. “This would have been difficult to do on our own. We would have had to devote staff time to find farmers. Having an organization we trust, know and respect like Purdue Extension really makes the path so much smoother and easier.”

From trash to trees

Growing in a container that's not ideal causes tree roots to curl.

While some in the college try to find a home for excess vegetation, others are addressing the opposite problem. Douglass Jacobs, Fred M. van Eck Professor of Forest Biology, and Owen Burney, his former doctoral student, often find themselves in places such as Haiti and Afghanistan where trees are desperately needed. “The amount of land that is being deforested and not replanted is still growing,” says Burney, now an assistant professor at New Mexico State University. “There is a significant need for an improvement of the nursery system that then translates to reforestation.”

Jacobs and Burney developed the Bottles to Trees program in response. With a few cuts and modifications, a discarded plastic soda bottle can work nearly as well to grow tree seedlings as the best technology on the market — and far better than the one-time-use seedling bags prevalent in these countries. The result has the added benefit of repurposing plastic that would otherwise contribute to local litter accumulation.

“Typically these bottles are just used once, and in many of these underdeveloped countries, they’re not even recycled because there is no market for recycling,” Jacobs says. “It’s quite possible we could produce forest tree seedlings in these plastic beverage bottles of higher quality than those in the bags that we see around the world.”

The seedling bags are cheap but cause seedling roots to spiral. When the roots reach the smooth sides of the bags, they grow horizontally in circles. That can choke plants and leads to shallow root systems and less viable trees.

The best seedling containers have ridges inside, which train roots to grow downward. But they can cost more than $1 per unit, and shipping them to remote places can cost far more than the container itself.

Above: In a more ideal container, tree seedling roots grow straight down into the soil, instead of curling. Below: Adding epoxy ridges inside the bottle or cutting slits in the sides of the bottle can encourage the roots to grow correctly.

Jacobs and Burney remove the tops of bottles, poke holes in the bottom for drainage and cut three slits along the sides. When roots reach the open air at those slits, they stop growing and don’t spiral. Using epoxy to add ridges to the insides of bottles has proven even better for root development. Jacobs and Burney hope to find industry partners, such as beverage companies or bottle makers, who might redesign their own bottles to include ridges, making them even easier to use as tree planters.

“Deforestation is a serious problem, but there is a solution,” Jacobs says. “And using these plastic bottles, we can solve this problem without even having to spend a lot of money. That’s the beauty of this.”

Strength in scraps

Strength in scraps

Classroom furniture in places like Costa Rica takes a beating. Rooms overflow with students who come to classes in shifts. Pair that overuse with the fluctuation of wet and dry seasons in the tropics, and the furniture doesn’t last long. Replacing it takes money away from other priorities.

Eva Haviarova saw that school furniture in many developing countries she visited was poorly designed with weak joints prone to breaking. Her solution was to design stronger furniture made from inexpensive scraps and otherwise useless small-diameter timber.

“There’s lots of residue material generated with local industry. There are also plantations that must regularly thin their trees, leaving behind small sticks,” Haviarova says. “All of this residue material can be made relatively easily into small parts and built into chairs or desks.”

Haviarova has also incorporated low-value, small diameter timber, sawmill cutouts, recycled furniture material and underutilized wood species as potential building materials. Some, including agricultural fiber waste, can be combined with plastic residues for tabletops.

Haviarova, associate professor of wood products in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources and director of the Wood Research Laboratory at Purdue since 2004, has taught the design to people in Costa Rica, Panama, Nicaragua, Uganda, Turkey and Afghanistan.

She is also teaching students, missionaries and workers in non-governmental organizations how to build the furniture with superior strength properties. They in turn use modular kits and toolboxes to teach the design and building processes to locals in several countries.

“If we could teach locals how to produce furniture components on simple equipment, and if everything is done right, they can easily assemble their furniture themselves,” Haviarova says.