JOIN THE TEAM

TO HALT HARMFUL SPECIES

BY EMILY TONER

In Vevay, a small Indiana town on the banks of the Ohio River, a homeowner spotted something unusual earlier this year: a fire engine red bug with small white spots and long black legs crawling around their property. They took a photo and sent it to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR). Seeing the image set off alarm bells at the IDNR. That bright little insect was the immature stage of an invasive planthopper, the spotted lanternfly, which sucks sap from plant tissues and does serious damage if it becomes established in a region.

IDNR investigated and triggered a statewide response. Along with the immature spotted lanternfly, they found the adult form of the insect and eggs, checking all the boxes for an exotic species invasion: the presence of a non-native organism known to cause harm that has established a reproducing population.

College of Agriculture researchers, staff and Extension specialists are members of the team that swings into action to prevent the spread of harmful species — and to educate the rest of us to help.

Steve Yaninek, professor of entomology, was one of the first to respond, as a member of the Indiana Invasive Species Council (IISC). “We knew a spotted lanternfly invasion was just around the corner,” he says.

The spotted lanternfly’s native habitat is in Asia, but it was accidentally transported to Pennsylvania in 2014, where it attacked plants including grapevines, fruit trees and maple trees. In addition to the direct damage from feeding on sap, the insect excretes the excess plant sap in a sticky residue that promotes sooty mold growth on infested trees.

To get the word out quickly, Elizabeth Barnes, exotic forest pest educator, and Cliff Sadof, professor of entomology, prepared an issue of the Purdue Landscape Report and ramped up distribution of the materials they’d prepared to help people recognize and report this pest. Purdue Extension’s 92 county offices serve as a resource for the IISC to spread the word, since early detection is key to managing damage from an invading species

Elizabeth Long, assistant professor of entomology, specializes in working with vineyard and orchard managers, and she’ll help Indiana residents in those industries apply control tactics learned from Penn State University.

MANAGING INVASIVES

Exotic, or non-native, organisms, including insects, plants, fish and microorganisms, cross into Indiana regularly. Only when a non-native organism begins to cause harm to the environment, human well-being or the economy does it escalate to the category of “invasive.”

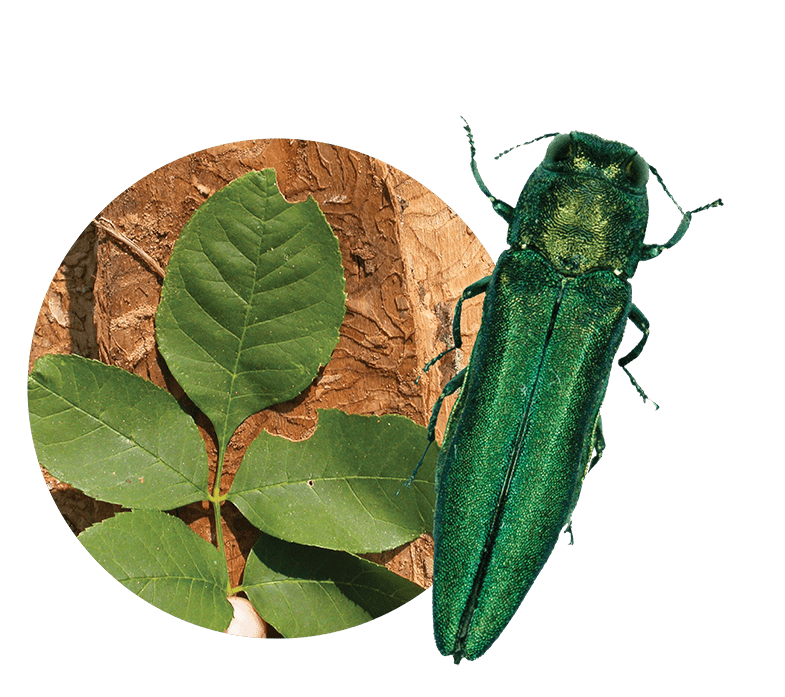

“Emerald ash borer burned through Indiana like fire,” Yaninek says. This invasive, wood-boring insect gets under the bark of an ash tree and kills it, leaving many small holes where the adult beetles emerge in its wake. The result is a dead, unstable tree with the structural integrity of Styrofoam, a dangerous tower that can fall during a storm or topple during tree removal.

Sadof and Barnes co-lead the national webinar education program Emerald Ash Borer University, offered continuously since 2009. This program connects experts on invasive forest species with people who need management advice and can help prevent the spread. One fundamental prevention tip: don’t move firewood, which could be infested with the beetle, from one location to another. When the emerald ash borer arrives, it kills 95 to 99 percent of ash trees in an area, leaving the tree effectively extinct in those locations.

“Economically, we talk about the property values of people’s houses. If you had a big, beautiful old ash tree in front of your house, but now just have a dead stump, that decreases your home’s value. Ash wood was also used in baseball bats, but now ash trees are a red-listed endangered species,” Barnes explains.

The webinar program has evolved to cover other types of invasive forest pests and pathogens; its most popular videos share all you need to know about spotted lanternfly and gypsy moth.

SPREADING THE WORD, NOT THE SPECIES

Awareness is key, given the wide range of invasive species. Plant scientists, ecologists, microbiologists, aquatic scientists, Extension educators and many others have a role in research and outreach on all types of invasive species.

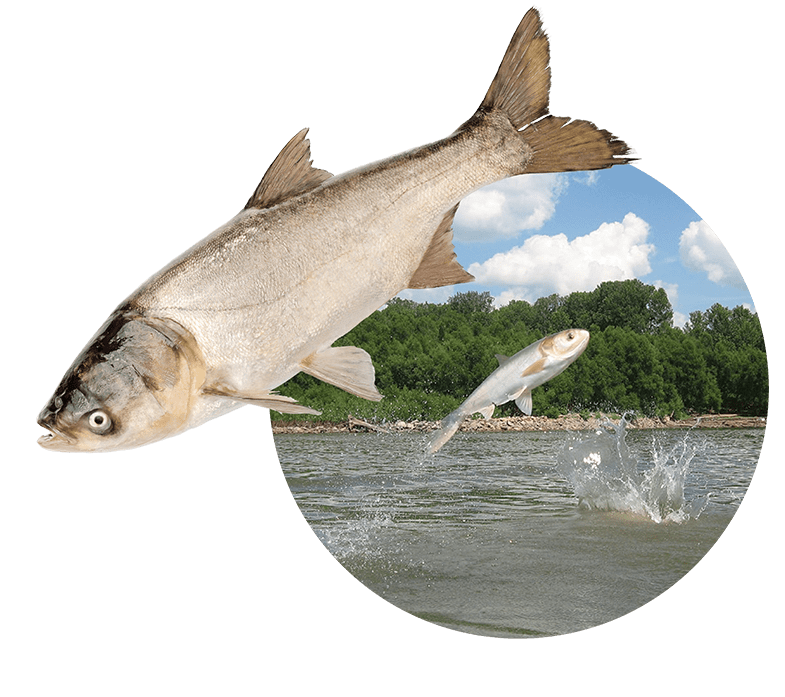

For example, two types of non-native carp, bighead and silver, threaten Indiana waters. They feed on plankton and disturb the base of the native aquatic food chain. Given their large size and weight, they can damage boats or hurt people when they jump out of the water.

“Even a 15-pound carp is like a real heavy bowling ball, and it’s going to hurt,” explains Reuben Goforth, associate professor of aquatic ecosystems in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources. Jumping carp have broken bones, caused concussions and even knocked people out of their boats, he says.

Goforth tracks the movements of invasive carp, which have no natural predator to keep their numbers in check in Indiana waterways. He helps monitor where they might spread next and how their reproductive cycle here differs from in their native Asian habitats.

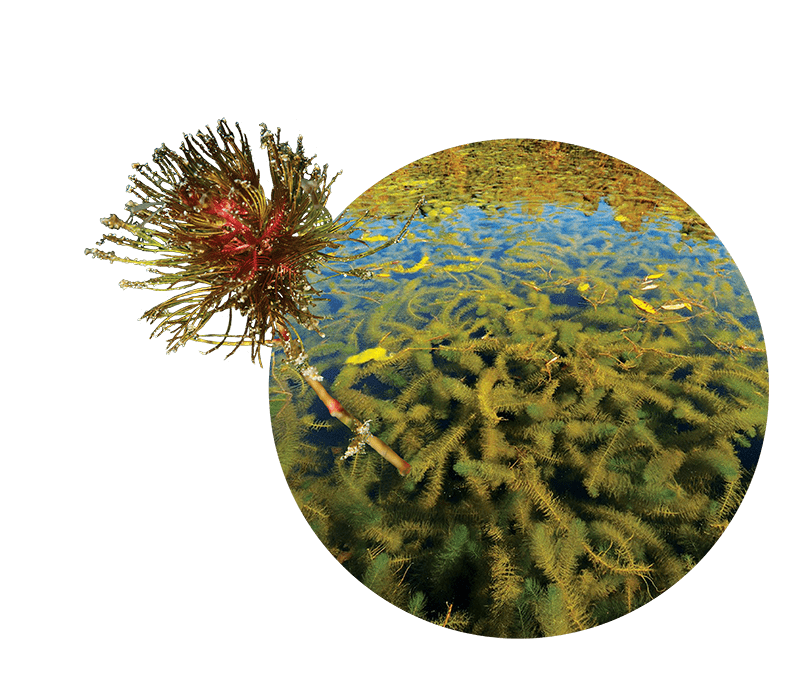

With carp and other invasive aquatic species such as zebra mussels and Eurasian watermilfoil (an invasive plant), it’s important to prevent physical movement of the species from one lake or river to another. Unfortunately, people frequently transport them by accident when moving their boats.

Zebra mussels expand their population quickly, clustering on all available surfaces with their sharp-edged shells. Lake users may be unaware of an invasion until their dock ladder becomes unusable — and by then, it’s too late to control the mussels. Preventing their spread by thoroughly washing boats after taking them out protects Indiana lakes, according to the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant’s program, Be a Hero — Transport Zero.

INVASIVE ANIMALS

SPOTTED LANTERNFLY JUVENILE

Photo: arlutz73/iStock via Getty Images

SPOTTED LANTERNFLY ADULT

Photo: Cwieders/iStock via Getty Images

SPOTTED LANTERNFLY ADULT

Photos: undefined/iStock via Getty Images and Neil/Adobe Stock

ZEBRA MUSSEL

Photo: arlutz73/iStock via Getty Images

EMERALD ASH BORER

Photos: Cliff Sadof, Purdue University and Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources - Forestry, Bugwood.org

SILVER CARP

Photos: bajinda/iStock via Getty Images and ©Laura Wharton/Adobe Stock

MAKING THEMSELVES AT HOME

A species’ ability to spread easily through a new location is a typical characteristic of invasive organisms, which tend to be tough and opportunistic about their habitat. Asian bush honeysuckle, for example, is an invasive with strong shade tolerance, which helps it establish under trees, where many other plants would struggle. Honeysuckle also produces large quantities of seed, has a longer growing season than many native plants and lacks natural pathogens or pests in the U.S., all of which makes it a supercompetitor that crowds out natives, fundamentally altering the ecosystem.

Unlike forests in many parts of the eastern United States, most of Indiana’s forests lack a thick natural shrub layer, explains Michael Jenkins, professor of forest ecology, who studies invasive plant management. Honeysuckle shades out native plants on the forest floor, with significant implications for the forest’s plant composition and soil as well as animals in the habitat.

For an animal, “Living off of honeysuckle berries is like trying to survive on Kool-Aid,” Jenkins explains, a comparison first drawn by his former graduate student Josh Shields, since the berries are prolific but not very nutritious. Jenkins and his collaborators discovered one mechanical approach to removing honeysuckle: using a machine head with grinding teeth that destroy the shrub’s base and shatter the root collar, where the stem emerges, is relatively effective. These recommendations can help busy land managers control invasive plants.

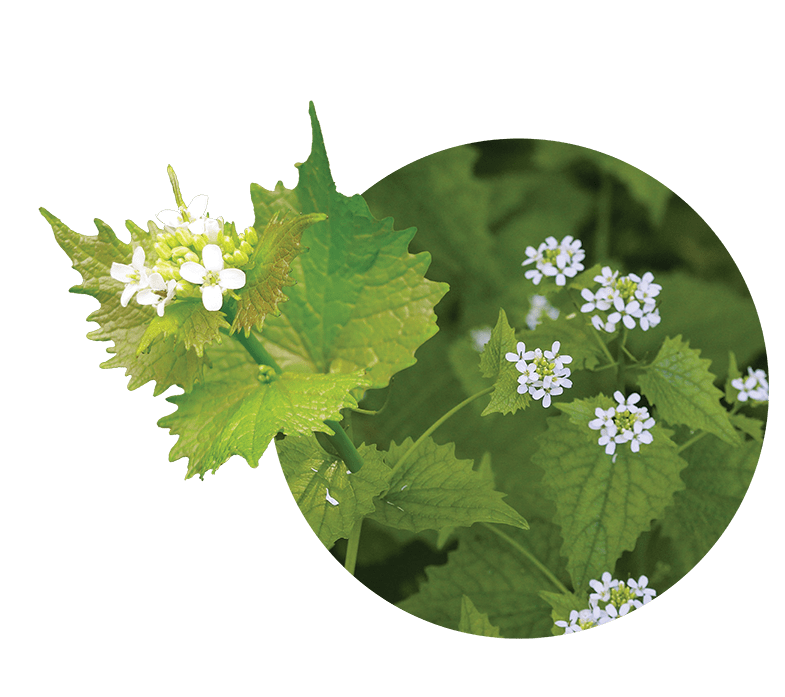

Typically, invasive plants are viewed as the drivers of undesired change in native plant communities; however, in some instances they are passengers that increase in dominance as the result of another disturbance. Native white-tailed deer are selective browsers, preferring to eat native species over most non-natives. Where deer are overabundant, their consumption of native plants can free up growing space for invasive species like garlic mustard. In field experiments, Jenkins and his collaborators showed that when deer are excluded from forest areas with fencing, native plant species increase in abundance, and native trees and shrubs can shade out invasive plants like Japanese stiltgrass, greatly reducing their cover.

MICROSCOPIC INVADERS

An invasive tree or fish is easy to picture, but some invaders are invisible. The Purdue Plant & Pest Diagnostic Lab (P&PDL) works to spot invading microorganisms, called pathogens. The invasive pathogens chestnut blight and Dutch elm disease killed millions of trees across the country. The former wiped out nearly every mature American chestnut tree from 1905 to 1940, changing the American landscape. The P&PDL is currently monitoring nursery stock to battle an invasive tree pathogen, Phytophthora ramorum, which causes sudden oak death. It’s prevalent on the West Coast and is being transported east. Other invasive pathogens like tar spot on corn can cause significant yield loss. Tar spot was first diagnosed in the United States by retired P&PDL diagnostician Gail Ruhl, who recognized it as different from any previous diseases she had seen on corn samples.

HIGH-TECH DETECTION

Digital technology can help detect invasive species early. Songlin Fei, professor of forestry and natural resources and director of the Integrated Digital Forestry Initiative (iDiF), uses complex data in his research to predict which forests are at risk for invasion. In a 2019 research article, he and his co-authors showed that 40 percent of U.S. forest plants are at risk of being invaded by the top 15 most damaging exotic species (six insects and nine diseases).

Researchers in iDiF use drone technology and new sensors to map the spread of invasive species and show where they are beginning to stress native trees. In partnership with the U.S. Forest Service, data are then shared in the public dashboard Alien Forest Pest Explorer. It tracks at a county level more than 80 non-native forest insects and diseases for the 48 contiguous states.

“My number-one thing is education,” Fei says. “Make everyone aware there’s an issue, so they don’t move infested firewood or plant an invasive species in the front yard as a way of spreading them. The second is early detection to stop the spread. Digital forestry can help us catch the frontiers of these outbreaks. Using what we’ve already learned, we can prioritize which species we need to keep an eye out for.”

INVASIVE PLANTS AND DISEASES

JAPANESE STILTGRASS

Photos: Chuck Bargeron, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org and Steve McDonald, Turfgrass Disease Solutions

GARLIC MUSTARD

Photos: Michael Meijer and Peter Fleming/iStock via Getty Images

SUDDEN OAK DEATH

Photos: Joseph O’Brien, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org

ASIAN BUSH HONEYSUCKLE

Photos: Liudmyla and AlexanderDenisenko/iStock via Getty Images

EURASIAN WATERMILFOIL

Photos: scubaluna/iStock via Getty images and damann/Shutterstock.com

CALLERY/BRADFORD PEAR

Photos: teeniemarie and 49pauly/ iStock via Getty Images

INVASIVES AND CLIMATE CHANGE

When a tree dies at the hands of an invasive species, another thing that disappears is its power to pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it as tree biomass. In the same 2019 article, Fei found that the carbon storage in trees lost to these pests each year is equal to the amount of carbon emitted by 5 million vehicles annually. Preventing tree deaths from invasive species can keep these natural climate change–fighting tools in place.

The ecology of invasive species intersects with climate change in other ways, too, explains Jeffrey Dukes, director of Purdue’s Climate Change Research Center. Dukes, professor of forestry and natural resources and biological sciences and Belcher Chair for Environmental Sustainability, says that higher carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere give some invasive species a boost to grow even faster. For example, research shows that the roots of Canada thistle grow thicker and deeper when given more carbon dioxide to work with, making the plant harder to kill.

As climate zones shift due to increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, native plants are losing their normal growing conditions. Changing climatic factors like warming temperatures, higher levels of precipitation or more frequent droughts can weaken a native plant’s ability to compete, Dukes explains, opening the door for plants like Japanese stiltgrass, an invasive understory grass, to gain a foothold. Historically this grass was a problem farther south in states like Tennessee; now it competes in southern Indiana.

In 2016, Dukes and his collaborators published research that globally analyzed where ecological communities are likely to undergo a major shift due to climate change and how prepared countries were to manage invasive species outbreaks. They identified countries that are most at risk for new invasions but lack comprehensive invasive species management policies.

Reporting and communication are key to managing invasive species in the midst of climate change, Dukes says. “There are more and more tools we can use to report invasive species, including smartphones.

”Combining information from databases around the country is also a goal. “Where are invasive species most abundant and having the most impact? What species are the worst invaders? We can only monitor that because databases are getting better. Managers can respond more quickly, and researchers can determine the nature of the problem we are looking at,” Dukes says.

WHAT CAN I DO?

- Learn more about invasive species in your area. In Indiana, start here.

- Report invasive species when you see them:

- Download a tracking app for your phone.

- In Indiana, send an email, or use this email address for aquatic invasive species.

- In Indiana, call 1-866-NO EXOTIC (1-866-663-9684).

- What else can I do?

- Don’t move firewood: buy it where you burn it.

- Plant native trees and shrubs. The Purdue Landscape Report can help with alternatives.

- Clean boats and other equipment from aquatic recreation after every use.

- Join a cooperative invasive species management area.

EDUCATION IS ESSENTIAL

Preventing an invasive species from establishing is by far the most successful management strategy. After it does, the results can be devastating to native ecosystems, leaving few options other than allowing the ecosystem to find a new balance over the course of decades, losing many native species in the process. For example, a 2020 Chicago tree census estimated the loss of 6 million ash trees to emerald ash borer. Of the 7 million that remain, 4 million are either dead or in decline. The result: a huge reduction in Chicago’s tree canopy cover.

Prevention requires experts from multiple disciplines not only to collaborate, but also to educate the general public. The case of Callery pear, or Bradford pear, is a good example of just how complicated invasive species prevention and control can be. It was originally brought to the United States from Asia as a blight-resistant rootstock and is now widely sold in the landscaping industry for its prolific white flowers in spring and bright leaf color in autumn. Unfortunately, when Callery pear escapes your front yard, it affects forests much like honeysuckle does: it easily outcompetes native wildflowers and trees in the understory and shades out small native tree sprouts that would eventually replace larger trees when they die.

The Indiana Invasive Species Council called the Callery pear, and its 20 different cultivars sold by Indiana’s nursery and landscaping industry, “one of Indiana’s greatest invasive species headaches.”

“We’re encouraging people to work past the aesthetics and recognize the environmental threat that Callery pear presents to biological diversity,” says Lenny Farlee, Purdue Extension forestry specialist. But with the high economic value of selling this popular tree, so far its sale has not been banned, like 44 other invasive plants in Indiana’s 2019 Terrestrial Plant Rule.

Alternative flowering trees that the industry could capitalize on include flowering dogwood, serviceberry, American plum and Eastern redbud trees, which provide beauty without the environmental cost. These native trees also avoid other downsides of the Callery pear: weak wood structure, which results in dangerous and unsightly breaking branches, and a particularly potent stench during spring flowering, which Farlee describes as “three-day-old fish.”

- Non-native insects, plants, fish, and microorganisms cross into Indiana regularly. They’re categorized as “invasive” when they establish a reproducing population and cause harm to the environment, human well-being or the economy.

- Invasive species in Indiana include the recently discovered spotted lanternfly, the emerald ash borer, bighead and silver carp, zebra mussels, Eurasian watermilfoil (an aquatic plant), Asian bush honeysuckle, garlic mustard, Japanese stiltgrass and Callery (Bradford) pear.

- Digital technology using drones and sensors can help predict where U.S. forests are at risk for invasive species damage.

- Climate change, such as increased atmospheric carbon dioxide, can boost the growth of some invasive plant species. Warming temperatures and changing precipitation levels can also alter normal growing conditions for native species, opening the door for invasive species.

- Invasive species include microscopic pathogens, such as those causing sudden oak death.

- See Purdue Agriculture’s comprehensive site for invasive species information.

- You can make a difference! See “What can I do?” above.

IT'S UP TO US

Without regulation and enforcement, preventing more planting of this invasive tree relies on individuals, who are the front line for combating many invasive species. Learning about invasive species can help people decide what to plant in their yard, when to clean their boats, and when to report an unusual insect.

“First and foremost: don’t give up hope,” Barnes says. “There are plenty of examples where we’ve been able to push back, and those invasive species are no longer as destructive as they were.”

“Don’t be embarrassed to send in a report if you’re not sure,” Barnes encourages. “Send it in! I would rather get a hundred pictures of moths that aren’t spotted lanternfly than miss one real observation of this pest.”

Purdue Agriculture, 615 Mitch Daniels Blvd, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2053 USA, (765) 494-8392

© 2024 The Trustees of Purdue University | An Equal Access/Equal Opportunity University | USDA non-discrimination statement | Integrity Statement | Copyright Complaints | Maintained by Agricultural Communications

Trouble with this page? Disability-related accessibility issue? Please contact us at ag-web-team@purdue.edu so we can help.