Story by Emma Ea Ambrose

Koia is a plant-based protein drink company, headquartered in Los Angeles, CA. The company’s co-founder, Maya French, recently made Forbes’ 2019 30 under 30 list. It is one of the country’s fastest-growing beverage brands, currently available in 75,000 retail locations.

Holic Foods, based in Middletown, IN, is a recently established natural foods company, which currently manufactures one product; its signature, creamy Jalapeñholic sauce. The Middletown facility employs roughly 40 locals, many who lost their jobs when a local manufacturer closed its doors.

At first, even second, glance these companies have little in common besides a commitment to supplying quality, natural products. Their origin stories differ vastly, but Koia and Holic Foods share a common denominator that played a role in their success.

“Our first co-manufacturing experience was in the neighborhood of $100,000,” Dustin Baker, Koia’s other co-founder, said. “It was the Food Science laboratory that was instrumental in developing our manufacturing process.”

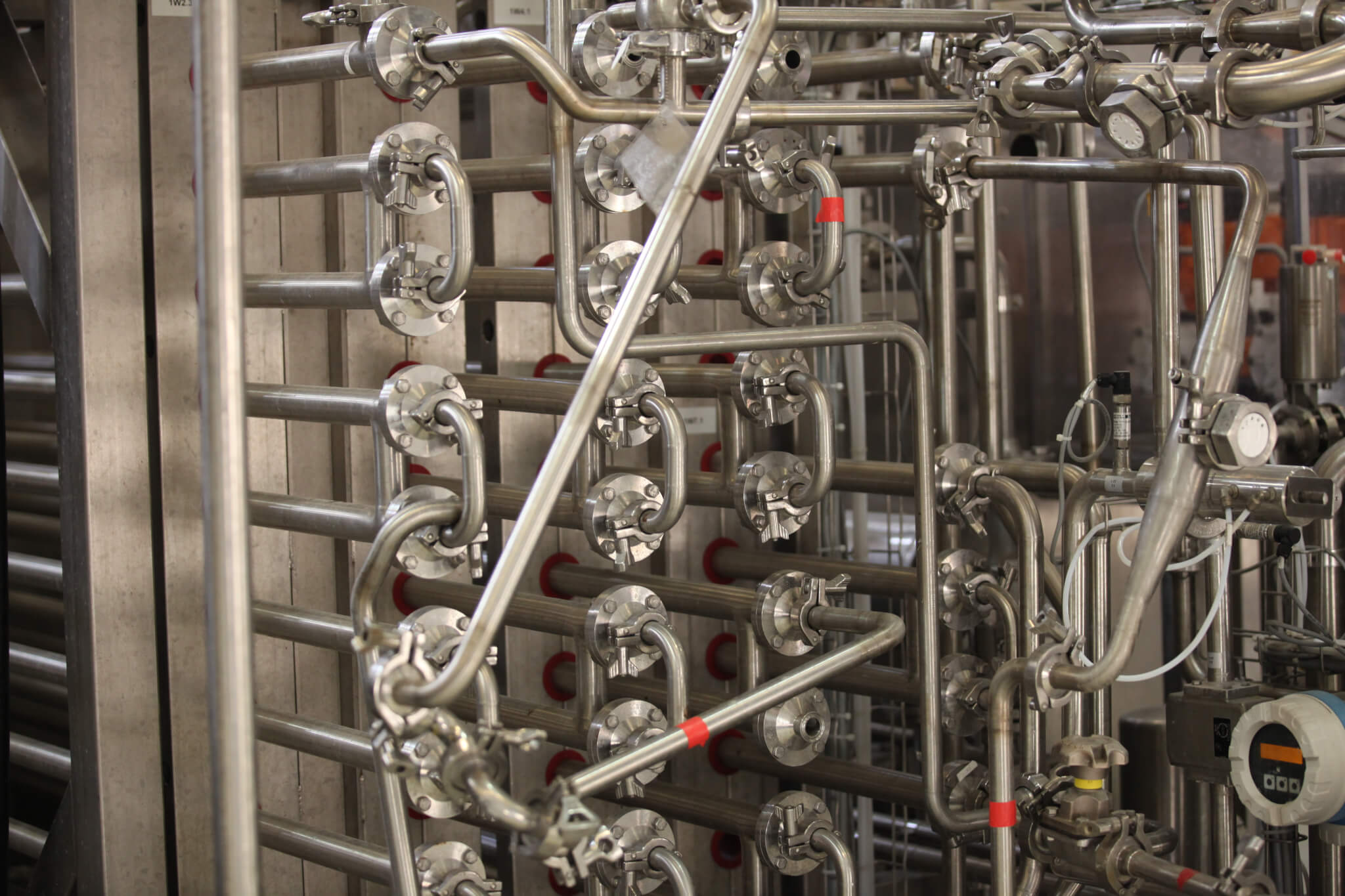

Baker is referring to the Department of Food Science’s Pilot Plant, a 10,000 sq. foot on-campus facility, outfitted with industry-grade equipment and technology. The lab is a space for students and faculty to experiment, problem-solve and stay up to date on technologies and processes. It is also a resource for companies and manufacturers looking to develop or refine a product or manufacturing process. Roughly 50 companies utilize the lab annually. As the lab’s capacity expands in terms of equipment, technology and human capital, the food science department is looking to increase use.

“We’ve started to really push the lab forward as far as the technology we can offer, its capacity and the breadth of work we can do in there,” Brian Farkas, professor of food science and department head, said. “In that space, we teach our next generation of food industry professionals, faculty conduct research in there and industry comes to us because we have the best equipment, the best space and, most importantly, the best people.”

That’s no secret to the founders of Koia and Holic Foods. Both companies partnered with the Pilot Plant at critical junctures in their evolution: Koia as it was transitioning from juices to protein drinks, which needed to have a longer shelf-life, and Holic as it was moving from selling its product at farmers markets to fulfilling an order from a major national retailer.

For a while Tonio Torres, who owns the company with his wife Frances Torres, said they were making vats of sauce at home, selling it at farmers markets and to friends and family. When an order came through from a national retailer, however, suddenly they were left scrambling, trying to figure out how to translate the nuances of home cooking to a manufacturing landscape.

“We really believe in bringing innovation to the American palate, but we just didn’t know how to do that on a large-scale or how to monetize our creation,” Torres continued. “When we couldn’t find a co-manufacturer we felt comfortable with we began the process of trying to figure out how to build our own manufacturing facility. Somewhere in the middle of this is when we got connected with the food science department at Purdue. When that happened was when we started making decisions, when things started clicking.”

That, said Brian Farkas, is exactly what he wants to hear from the businesses that utilize the plant, that the plant was instrumental not just in developing a product but in contributing to the growth of a business.

“In the end, the object is to help a company or individual realize their dream,” Farkas added. “In that vein, however, we’ve also talked people out of things. We’ve had people come in saying ‘Oh-but I’ve been doing it this way for years and selling the product’ and we tell them ‘OK, but now you really need to stop.’ We explain why it’s a bad idea and then help them produce it safely.”

Torres said working in the Skidmore Product Development Lab with students and lab manager Erik Kurdelak changed his understanding of food production. The plant, he explained, was a low-risk trial at food manufacturing and when things went wrong or a process failed, Erik and his team were there to trouble-shoot and draw on expertise throughout the department.

“Working with the Pilot Plant allowed us to be prudent about our investments. There was equipment we were ready to pull the trigger on that we realized we didn’t need,” Torres continued. “It brought us new insights on what processing looks like and how to leverage equipment and technology to make manufacturing more efficient.”

French and Baker said their experience was similar. There were several ingredients they had their hearts set on for the protein drinks, like chia seeds and coconut sugar, but when it came to running them through the equipment it clogged the machinery or didn’t produce the desired texture. Being at a university, however, French said you have a bottomless well of knowledge to draw on, all the way from the students to the faculty. Eventually all their issues with ingredients were ironed out without compromising the integrity of the product.

“The Pilot Plant is great during the bootstrapping phase because you are able to learn a lot and be very hands-on with your product,” French continued. “When you develop it at the plant it’s your baby because you were there.”

French said they relied a lot on the enthusiasm and diligence of students as well as the expertise of faculty and Kurdelak. Food science students working in the Pilot Plant find product development invigorating for the same reason business owners like French, Baker and Torres find it daunting: the inevitability of complications. For A’Lee McGrue, a sophomore food science student, this is an invaluable experience when it comes to preparing to enter the food production and innovation sector.

“This work teaches you how to think on your feet,” she said. “And there’s a puzzle aspect to it. I always look at the finished product and then work the process backwards, which requires a certain degree of familiarity with the equipment and the science.”

Students Erin Sukala, a junior, and Noah Van Horn, a senior, seconded this and said this is what employers in the food industry are looking for. Not everyone graduates a food science program with hands-on experience, never mind troubleshooting experience.

“In interviews for internships the interviewer has been impressed with my experience, they like that I haven’t just been confined to a lab. Yes, my experiences here have shown me how easily things can go wrong but that is what makes you a problem-solver,” Sukala said.

Another thing employers like seeing? Students who have worked with industry partners developing a shelf-ready product. “This is the closest thing at a university you can get to real-world application,” Van Horn explained. “When speaking to a potential employer I can actually refer back to products I’ve helped develop, which gives them a reference point for my skill level.”

That experience with industry partners helps graduates secure employment is no happy accident, Kurdelak said, it’s by design and one of the many reasons industry is invited to make use of the plant’s facilities. Food science graduates go on to work at companies around the world, but many do stay in Indiana, using their experience to grow the industry in-state.

“When you think about the agricultural strength in Indiana, food science is positioned right at the point of conversion,” Kurdelak said. “We are moving the crops into finished products. It’s important for us to support emerging businesses, our existing industry partners and our students, who will one day move into roles within those or similar companies. They don’t just need to be competent to walk through the door, they need to be ready to lead.”

At the nexus of agriculture and manufacturing, Indiana has a robust food manufacturing industry, but it can always be stronger, Farkas said, and the Pilot Plant is critical to that aim. Even if an industry partner isn’t based in the state, the experience the students receive from that partnership, the exposure the plant obtains from that relationship and the resources that company might eventually put into the Pilot Plant all benefit Indiana’s economy.

“Look at Holic Foods,” Kurdelak said. “Look at their physical location in the state, where there’s been a lot of economic hardship. They’ve been able to hire some of those people on and, more generally, they are supporting their community and growing the industry. And they got their start here.”