Land-Grant University to

the World

Land-Grant University to

the World

BY EMILY MATCHAR

Purdue: Land-Grant University to the World

Darrin Karcher, associate professor of animal sciences, is a poultry management expert, so in most ways the assignment was typical: help a group of farmers figure out how to improve their egg yield.

But unlike many Purdue Extension projects through Purdue’s College of Agriculture, this one was not in Indiana, but some 2,500 miles southeast, in the Caribbean nation of Trinidad and Tobago.

Leah Thompson is a graduate student in the Department of Animal Sciences, so she’s used to field work. But this field work was far from the corn and soybeans of the Midwest — in Battambang Province, known as the “rice bowl of Cambodia.”

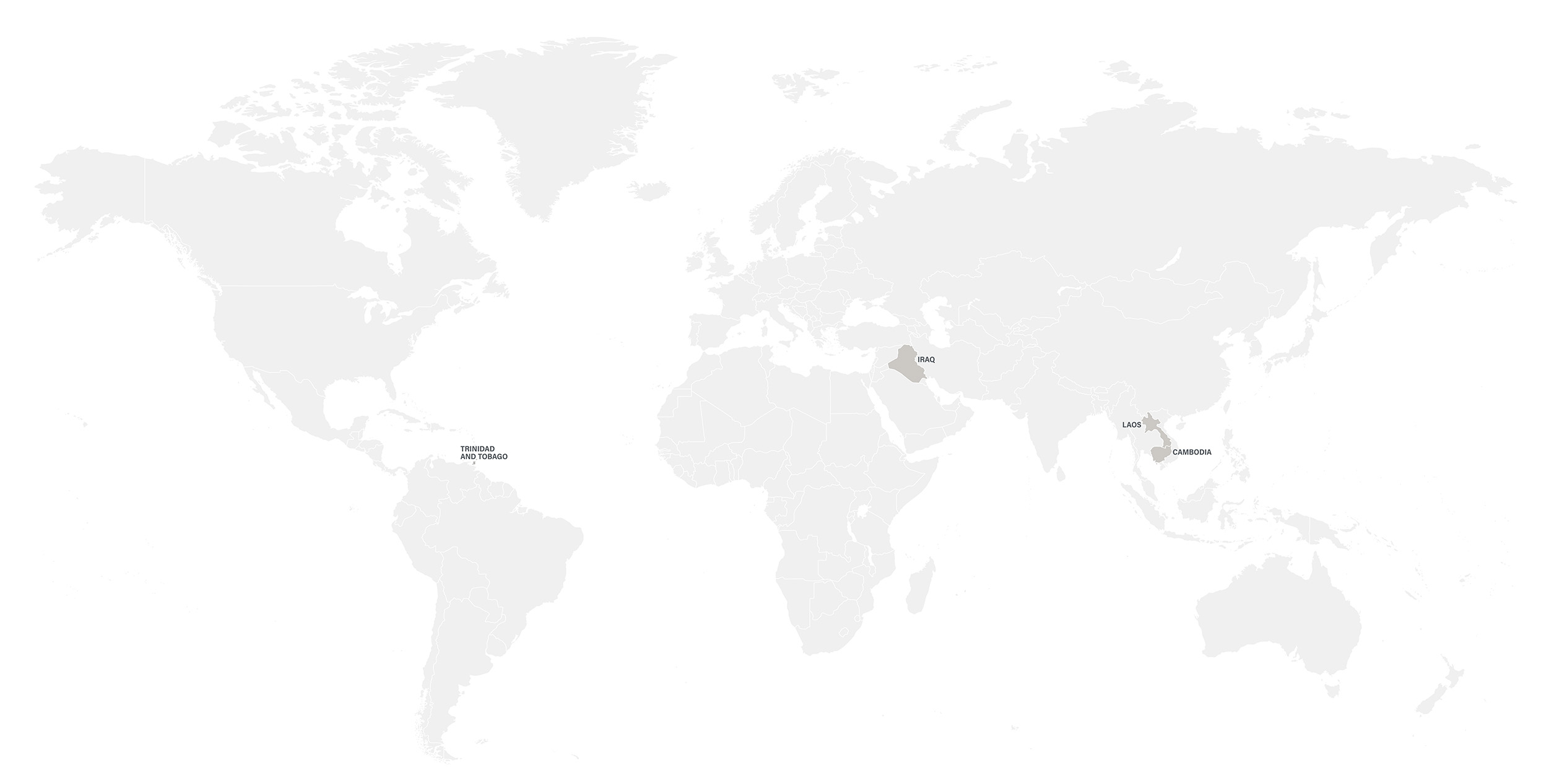

While these landscapes were new to Karcher and Thompson, international projects are not new to the College of Agriculture. Purdue Extension specialists and students are involved in programs across the globe, from Trinidad and Tobago and Cambodia to Iraq and Laos. They partner with local universities, government agencies and other stakeholders, working to teach and build capacity.

“There’s a long tradition in the College of Agriculture of participating in international capacity building. It’s in our DNA,” says Gerald Shively, professor of agricultural economics and associate dean and director of International Programs in Agriculture (IPIA). “It grows out of the land-grant mission: the idea that you’re taking knowledge to where it’s needed.”

Where is it needed? All over the world.

PRODUCING EGGS — AND LIFE SKILLS

Karcher’s Trinidad and Tobago project was part of The John Ogonowski and Doug Bereuter Farmer-to-Farmer Program (F2F), which “provides technical assistance to farmers, farm groups, agribusinesses and other agriculture sector institutions in developing and transitional countries” and is supported through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Karcher’s two-week assignment was to help a group of men recently released from prison develop agricultural skills for their reintegration into society. “The goal was to give them the capacity that they would have some knowledge they could work into potential employment opportunities, or they could start their own small business,” he says.

Karcher gave the group daily lessons on different aspects of egg production, then worked to implement the lesson in a hands-on way. “For example, we talked about how to set up the pen for brooding baby chicks, then we got the materials and worked as a group to set up the brooding pen,” he says. Ultimately, Vision on Mission, the nongovernmental organization that provides the rehabilitation services, increased egg production by 150%.

The project gave Karcher the satisfaction of an immediate result. “The extension work we are doing tends to be more focused on medium- and long-term impacts,” he says. “To be able to be in Trinidad and Tobago for two weeks and see the change that has occurred as a result of what you did with them was huge.”

The model of universities with extension programs offering education and outreach is not universal, explains Amanda Dickson, international extension specialist in IPIA, who led the F2F project at Purdue. In many countries, research takes place in universities, while outreach takes place through government agencies such as a ministry of agriculture. But universities and government agencies don’t always have clear channels of communication, so translating the latest research into community outreach can be challenging.

“In an ideal world there’s this loop — extension staff out in the country are aware of current problems that farmers are experiencing; they relay that message to researchers on campus, and researchers find solutions to those problems,” she says. “That’s the amazing advantage we have here in the United States.”

“It grows out of the land-grant mission: the idea that you’re taking knowledge to where it’s needed.”

Gerald Shively, professor of agricultural economics and associate dean and director of International Programs in Agriculture (IPIA)

KNOWLEDGE-SHARING IN IRAQ

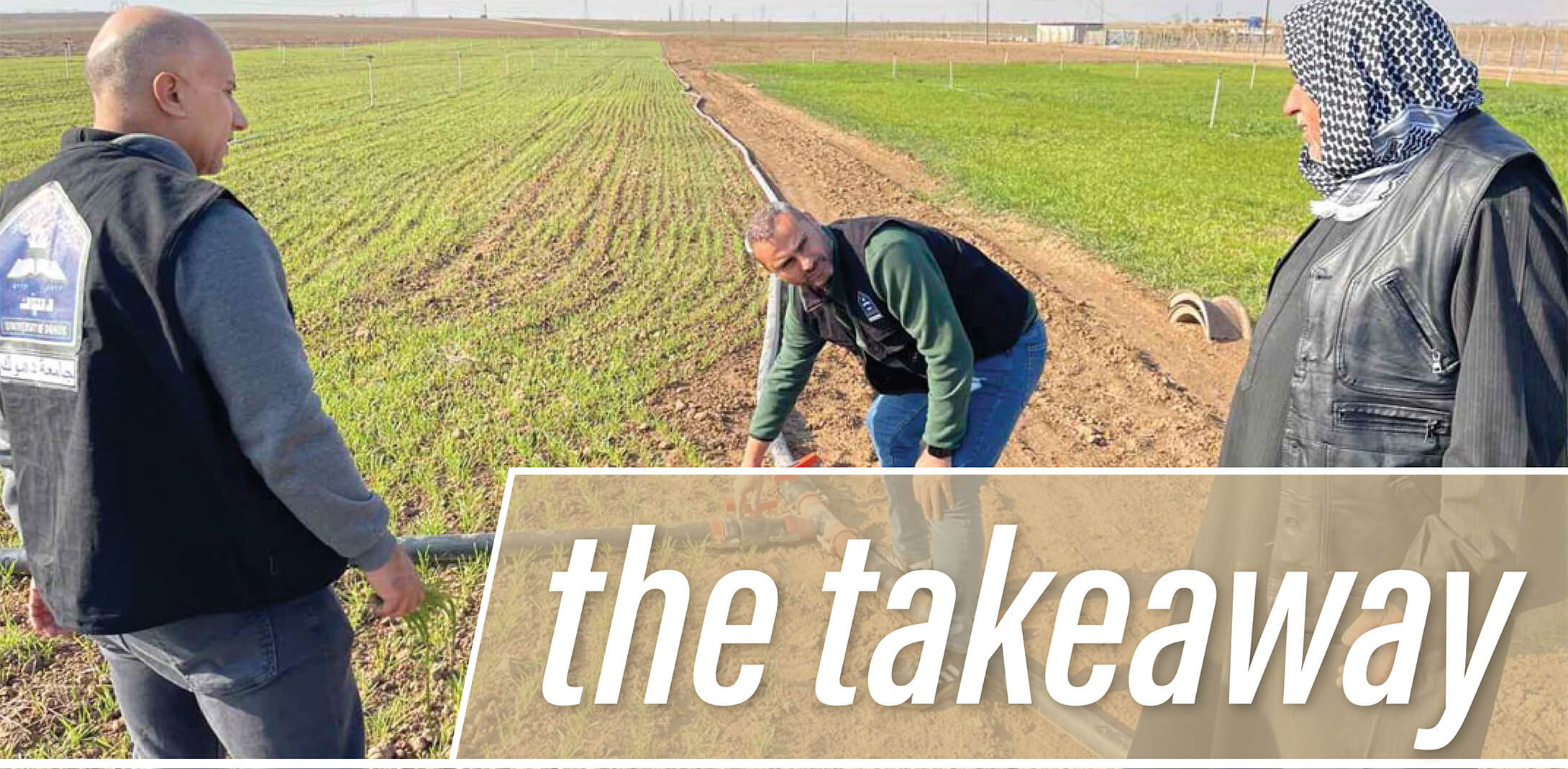

Purdue Extension’s knowledge-sharing can play an especially critical role in places where conflict has disrupted agriculture. In northern Iraq, minority communities are trying to rebuild after the devastating occupation by ISIS from 2014 to 2017. During that time, members of these communities, including Christians, Yazidis, Shabaks, Turkmen and Kaka’i, were killed, enslaved, displaced and forcibly converted. Those who survived found their agricultural livelihoods destroyed.

Purdue is part of an international consortium, led by Notre Dame and including Iraq’s University of Duhok, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute and Indiana University, helping create a framework for rebuilding.

“The part we’re working on is, ‘How does the university there engage their society and get information from the university out to the farmers and the society as a whole?’” says Peter Hirst, professor of horticulture and associate director of IPIA. “That’s something we in the land-grant system know because we’ve been doing it for over 100 years.”

“The extension system is a trusted source of information. People know us. In other places, that trust has not been established, so people don’t necessarily call on the university for information. To try and establish those linkages takes time.”

Peter Hirst, professor of horticulture and associate director of IPIA

Hirst, along with colleagues Dickson and Mark Russell, professor of agricultural sciences education and communication, traveled to Iraq last year to meet their Iraqi counterparts and learn about their environment. After the trip, they hosted their Iraqi colleagues here in Indiana. They took the delegation to visit the Department of Agriculture, Indiana Farm Bureau and various farmer organizations. They wanted to demonstrate how Purdue Extension works with partners on common goals.

“We take it for granted here in Indiana and the United States that people look to universities for information,” Hirst says. “The extension system is a trusted source of information. People know us. In other places, that trust has not been established, so people don’t necessarily call on the university for information. To try and establish those linkages takes time.”

SPEAKING THE LANGUAGE OF SCIENCE

Gerald Shively’s mission seemed difficult, but at least straightforward: help Laos build capacity to fight child malnutrition. Then he learned about the Lao word for “protein.” “When we first started having conversations with stakeholders in 2019, one of the things that became apparent was that there wasn’t a really good understanding of how scientific terms and concepts translated between English and Lao,” Shively says.

For example, the Lao words for “meat” and “protein” are often exchanged. This means that talking about increasing protein by eating more tofu, for example, could confuse a Lao speaker. So Shively’s team and his Lao colleagues set about creating an English–Lao nutrition dictionary.

That was one of many steps in Shively’s four-year project, supported by USAID’s Long- Term Assistance and Services for Research (LASER) Partners for University-Led Solutions Engine (PULSE) consortium. Purdue’s College of Agriculture and College of Health and Human Sciences led the initiative in conjunction with Indiana University and Catholic Relief Services.

Purdue and the other international team members worked with Lao government agencies and universities to strengthen research capacity, develop training programs and create the structure for sharing information with stakeholders. Purdue, Shively says, was in an ideal position to participate in such a project because of its “deep bench” of experts and long tradition of international work, which goes back to at least the 1950s.

IPIA has been around since 1965. For decades it was “the only unit on the Purdue campus with an explicit mandate to pursue international engagement,” Shively says. Its initial focus was on deepening ties between the College of Agriculture and Brazil’s Federal University of Viçosa (UFV).

Purdue faculty members spent years living in Brazil, and by the end of the program, “UFV had been transformed from a rural vocational school to one of the finest universities in South America,” he says.

As director of IPIA, Shively has a part in many of the college’s international projects.

“Whenever those mission areas have an international component, IPIA tends to get involved,” he says. “Most of the time we’re trying to facilitate the work of others — trying to identify where there are opportunities and assembling teams to go after those opportunities.”

CULTURAL EXCHANGE IN CAMBODIA

Leah Thompson, a doctoral candidate in animal sciences, had only been abroad once before coming to Purdue as an undergraduate. Her college experience, which included several exchanges and overseas projects, helped spark her passion for learning about other cultures.

“I’ve had really great mentors who have provided me with opportunities,” Thompson says.

As a graduate student, Thompson became involved with the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Safety, a USAID virtual hub of international food safety projects co-run by Purdue and Cornell University. Through Feed the Future, Thompson traveled to Cambodia several times to work on vegetable safety, including how to identify and reduce risks of contamination along the value chain. Purdue’s Paul Ebner, professor and interim department head of animal sciences, and Kansas State University’s Jessie Vipham lead this project.

Although her degree will be in animal sciences, Thompson is also interested in the human side of agriculture, particularly gender roles. In Cambodia she studied how responsibilities for vegetable production were divided according to gender.

“If we were to try to implement any kind of food safety intervention like a vegetable wash, it would be unsuccessful unless women are meaningfully involved throughout that entire process,” she says.

In Cambodia, Thompson and her team partnered with the Royal University of Agriculture in the capital of Phnom Penh, with project sites in two provinces. Although Thompson doesn’t speak Khmer, she tagged along with translators to interview rural farmers, building relationships as she went and learning about the country’s difficult history.

“I didn’t know about that. I wasn’t taught about it,” she says of the genocide the Khmer Rouge regime perpetrated in the 1970s, which killed approximately a quarter of the nation’s citizens.

Thompson’s connections would prove not just professionally helpful, but lifesaving. The day before she was to fly back to the U.S. in 2023, she had a medical emergency and was hospitalized. She needed blood transfusions, but Cambodia does not have a sufficient public blood supply, with most donations coming directly from family and friends. Thompson’s colleagues, including people she didn’t know well or couldn’t talk to because of language barriers, immediately stepped up to donate their own blood. Several friends and colleagues took turns visiting her in the hospital every day.

“They would try to bring me fresh coconuts; they knew the fruits that I liked and the snacks,” she says. “You just can’t really put into words how that makes you feel. Cambodia will always, always have a special place in my heart.”

THE BENEFITS RUN BOTH WAYS

It’s clear how international work benefits the countries where projects take place, but this work also benefits Purdue researchers, the university and even the United States.

International work “helps extension staff reinforce and expand upon skills,” Amanda Dickson says. “These experiences can have an immense value and impact for them individually, as well as the wider extension service and the communities they serve.”

International extension work also helps build cross-cultural competencies, Dickson adds, which is increasingly important as demographics are changing in Indiana and nationwide. And it keeps the university globally competitive and relevant. “Purdue, and in particular Purdue Agriculture, is well known worldwide,” Dickson says. “When you travel and start talking to people from other countries and say ‘Purdue University,’ they instantly know that name.”

On a larger scale, international extension work can benefit relationships between countries. The United States and Laos have had chilly relations since the Vietnam War, when the U.S. dropped 2.5 million tons of ordnance on neutral Laos. Some 20,000 civilians have died from accidental encounters with unexploded bombs in the decades since. Recent attempts at bridge-building have included government money and support toward removing unexploded ordnance, cultural exchanges, and stronger business and development ties.

“The U.S. has not traditionally had a strong development presence in Laos, but relations are now warming,” Shively says. “This was an attempt to build more positive collaborations with the country. That’s one of the reasons I was interested in the project — the chance to do something positive and to work in a place where not very many people in U.S. universities get to work.”

That her job as international extension specialist even exists is a testament to Purdue’s international mindset, Dickson says. “Purdue values global work so much they’re willing to put resources into a position [like mine].”

The benefits of such international work come back to Purdue multiplied, she adds. “It strengthens institutional capacity in research applications as well as finance and logistics management, and provides amazing professional development opportunities for faculty and staff.”

- The College of Agriculture and Purdue Extension share expertise where it is needed, from Indiana to places around the globe, as part of Purdue’s land-grant mission.

- Projects described in this story take place in Trinidad and Tobago, Cambodia, Iraq and Laos — but there are many others.

- International work in the college primarily aims to help increase the capacity of international researchers, develop training programs and create pathways to share research with those who need it.

- The college’s Office of International Programs in Agriculture was formed in 1965, working first with Brazil’s Federal University of Viçosa, but the college’s history of international engagement dates back to the early 20th century.

- International extension offers members of the Purdue community professional development, fresh ideas and an infusion of energy. It also provides experience with diverse cultural practices, which is important as demographics change in Indiana and nationwide.

- International extension also keeps Purdue globally relevant and competitive, and can enhance relationships between countries that may lack strong diplomatic ties.

Fathi Abdulkareem Omer and Hojeen Majid Abdullah of the University of Duhok Extension team visit the Nineveh Plains of Northern Iraq to assess and address farmers' needs.