SAFETY FIRST

IN THE GLOBAL FOOD SUPPLY

BY EMILY MATCHAR

Photo courtesy of FSIL by Andrew Ball

Those of us at the consumer end of the food production chain don’t necessarily think about food safety much. Sure, we know to cook chicken thoroughly and never let potato salad sit out too long in the heat. We read the occasional news story about a foodborne illness outbreak and remind ourselves to wash our lettuce and scrub our cantaloupes extra carefully.

But the overall, exceptional safety of our food supply comes thanks to hard work, research, data analysis, education and outreach by people all along the food production chain. At Purdue, food safety researchers are deeply involved in this process at every step. Their work helps ensure that the chicken on our plates, the herbs in our spice racks and the milk in our children’s glasses won’t make us sick.

UNSEEN THREATS

“I like the scary side of food,” says Haley Oliver, 150th Anniversary Professor of Food Science, on why she went into food safety.

Oliver grew up on a family farm in rural Wyoming, about 100 miles from Cheyenne. She was always interested in agriculture, but when she got to college, she had to take a microbiology class to fulfill a general science requirement. “It was the hardest class I’ve ever taken in my life,” she says. “I loved it.”

For Oliver, food safety turned out to be the sweet spot between microbiology and agriculture. She earned her PhD at Cornell, studying listeria, one of the most dangerous microbes in our food supply.

Listeria and its brethren — microbes like E. coli, salmonella, and campylobacter — are known in the food safety world as biological hazards, one of three main categories of threats. The other two are physical and chemical hazards. Physical hazards include things like rocks or bugs in the food supply that can typically be seen and removed. Chemical hazards include misuse of pesticides or herbicides. “You might have the best-looking lettuce on the planet, but if it’s loaded down with pesticide, it’s a chemical hazard,” Oliver says.

Biological hazards are trickier. They’re invisible to the naked eye yet cause the most illness. This can be confusing to food producers unfamiliar with the microbes or the diseases they cause. “I tell you there’s salmonella in chicken, and you’re thinking, ‘Salmonella? I can’t see it,’” Oliver says.

Oliver has dedicated much of her career to studying these biological hazards. She currently directs the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Safety (FSIL), funded by USAID as part of Feed the Future, the U.S. government’s global hunger and food security initiative. FSIL, the result of a $10 million grant won by Oliver and her colleagues at Purdue and Cornell, runs programs to improve food safety in Nepal, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Nigeria, Kenya and Senegal.

Oliver calls winning the USAID grant one of the most difficult things she’s ever done but also one of the most rewarding. FSIL’s programs work with international partners, including farmers and local researchers, to address the root causes of biological foodborne illness. Scientists from U.S. Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs), colleges and universities that serve largely minority populations, administer a portion of the programs. These include Texas State University, Tennessee State University, Tuskegee University and the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Each project focuses on a different approach to reducing foodborne illness. In Senegal, FSIL is helping small farmers understand and implement procedures for making dairy products safer. In Bangladesh, they’re working on safety in the supply chain of fish and chicken. The Cambodia project involves identifying where in the food chain vegetables may become contaminated and helping food workers avoid these hazards. In Kenya, the project is known by its Swahili name, Chakula Salama, which means “safe food.” Researchers are working with small, often woman-run farms to mitigate risk of salmonella and campylobacter in poultry. The Nepal project is helping train producers and consumers to make safer decisions around raw produce. The Nigeria work aims to better understand and improve household food safety practices.

In one FSIL project, researchers are identifying areas in the value chain for fish and chicken, such as in markets and during processing, where food safety interventions could reduce foodborne illnesses. Photos courtesy of FSIL by Faron Foot and Allison Joyce.

Oliver loves the challenge of working on these kinds of projects, which draw from so many fields of expertise: chemistry, horticulture, animal science, microbiology — even psychology and economics. “It just underscores the awesome interdisciplinary nature of a college like ours,” she says. “It takes all of us.”

Cornell’s Randy Worobo, professor of food microbiology, says running the lab between two universities means more brainpower. “You double the amount of expertise from everything from food microbiology to food science,” he says. “It’s really a win-win.”

Between them Worobo and Oliver try to visit each of the projects about once a year — another benefit of the collaboration. “Being in close contact with the in-country USAID staff is essential,” Worobo says.

It’s critical to understand food producers’ motivations, which are often economic, he explains. A small dairy operator may understand the risks of bacteria in raw milk. But if he or she can’t afford to pay for pasteurization, that knowledge does little good.

“This is where having an agricultural economist to actually work out how much money it costs to run a pasteurizer versus how much they’re going to lose in spoilage matters, to show them in dollars what [pasteurization] could save them,” Worobo says. “You really have to adapt to what’s important to them.”

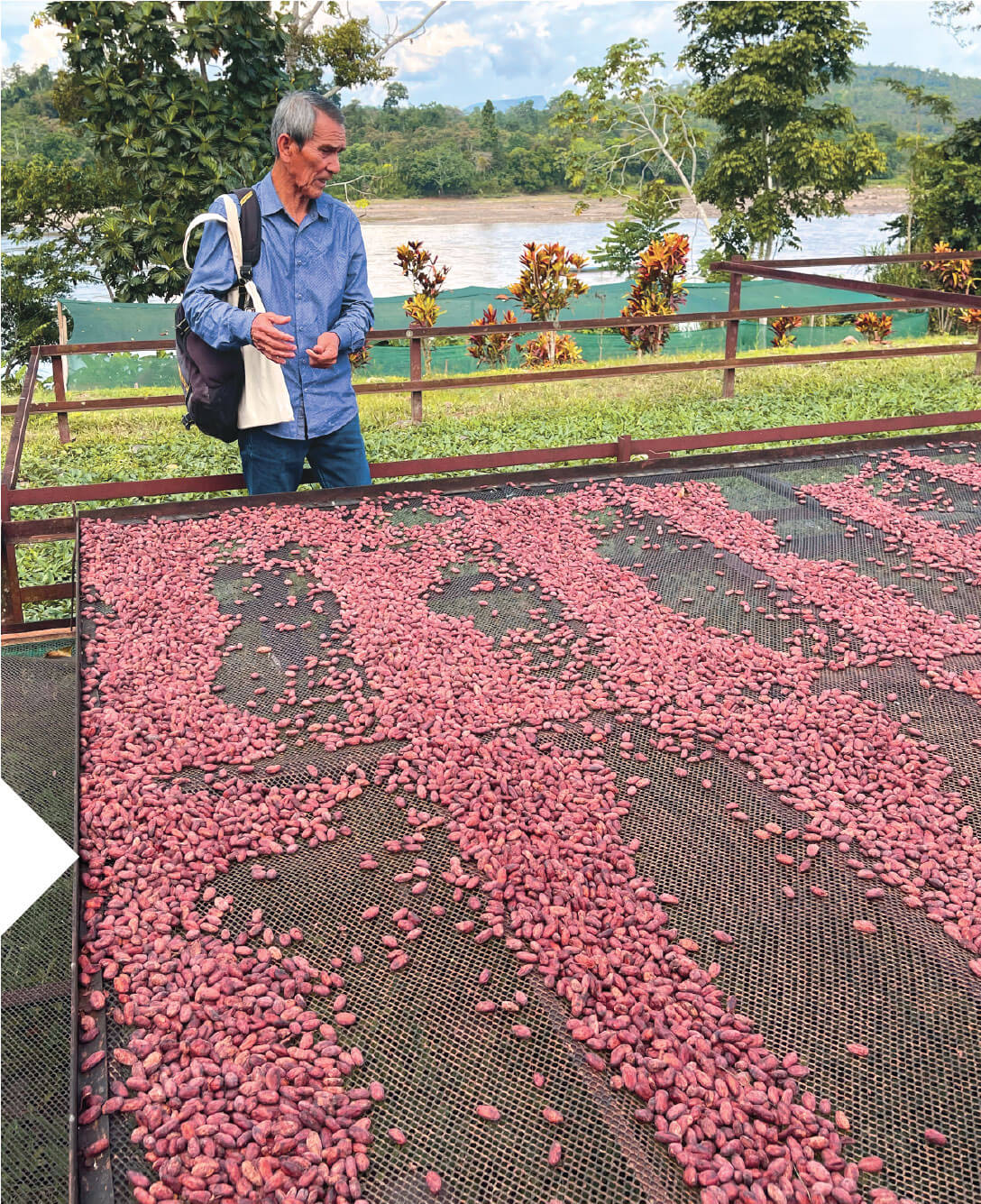

Amanda Deering leads a USAID-funded project in the San Martin region of Peru. This work aims to help transition coca growers to other crops that can be transformed into value-added food products.

FROM COCAINE TO CHOCOLATE

Like Haley Oliver, her frequent collaborator Amanda Deering grew up on a farm — in her case, in Michigan. Deering studied biology as an undergraduate and grew fascinated by plants and bacteria. “I hated anything to do with animals or humans,” she says, laughing.

After college, she earned a master’s degree in plant biology and then came to Purdue for a doctorate in food microbiology. Around the time of her graduation, a major foodborne illness outbreak was traced to cantaloupe in Southern Indiana. Growers told the university they needed someone who was dedicated to food safety in the produce world. So Deering filled that role and is now an associate professor of produce food safety.

Deering helped cantaloupe growers identify contamination points. The major issue turned out to be so-called “dump tanks” — concrete pits where melons were sanitized en masse. Unfortunately, since all the cantaloupes touched the same water, a single contaminated melon could contaminate the whole crop. Farms quickly got rid of the dump tanks.

“So far, so good,” Deering says. “We haven’t had any recalls since then.”

Deering manages produce safety trainings at the Purdue Extension Food Safety Training Hub, located at the Vincennes University Agricultural Center near one of Purdue’s research farms. These trainings ensure that farmers comply with the FDA’s 2011 Food Safety Modernization Act guidelines.

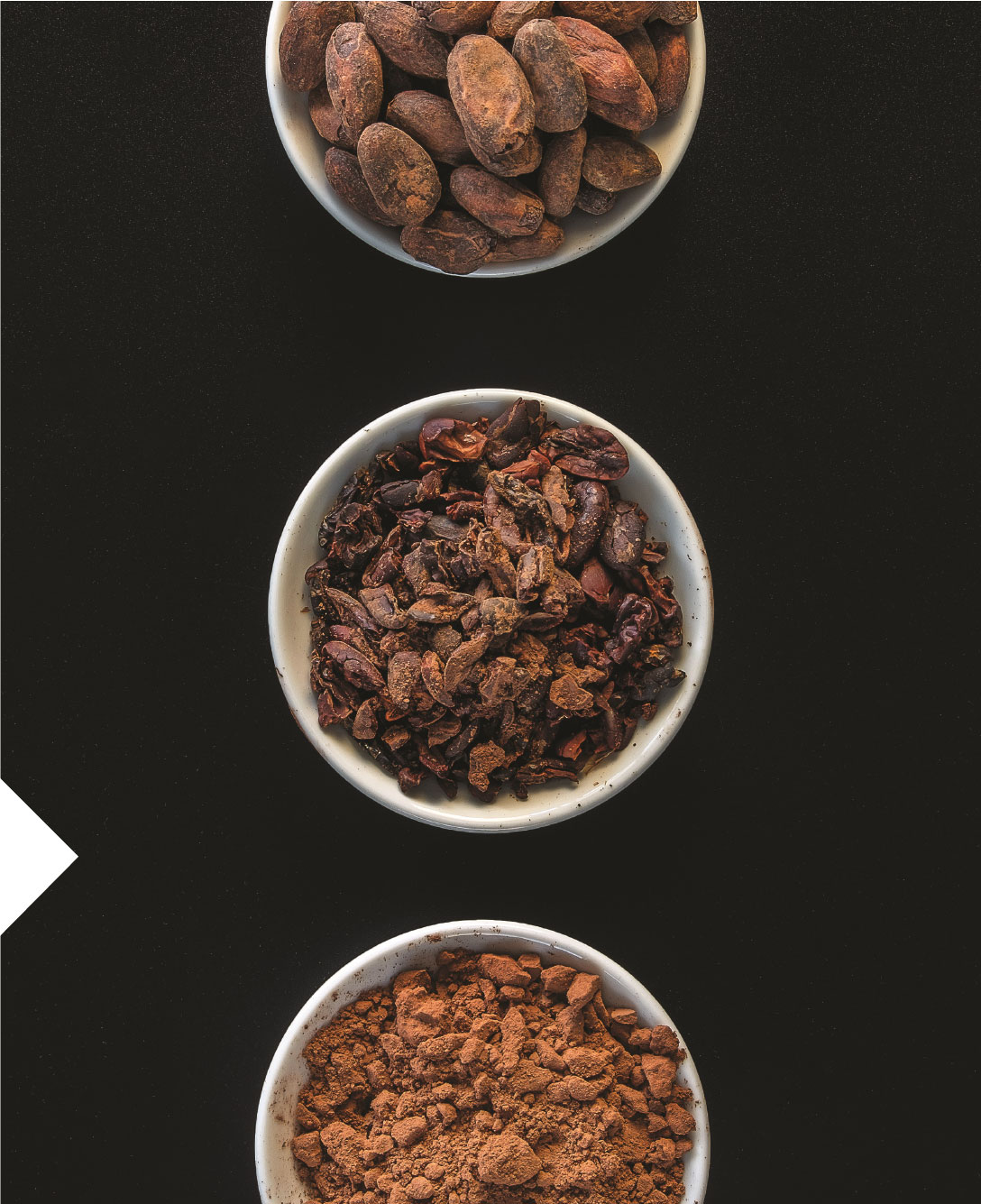

Deering is also involved in international work, collaborating with Oliver and Professor of Animal Sciences Paul Ebner on helping build a food technology department at Herat University in Afghanistan in the mid-2010s. Her latest project, part of a $15 million USAID grant, involves helping farmers in Peru find alternatives to growing coca, the raw material for cocaine. One possibility is cacao, the raw material for chocolate.

“Where we come in is helping them transform those raw agricultural commodities into something value-added,” she says.

That means not just selling cacao beans, but actually turning them into more lucrative chocolate. This may not seem an obvious link to food safety, but it is in a different way. Turning from coca to cacao means cutting off a dangerous drug trade, potentially saving lives.

DON’T BELIEVE EVERYTHING YOU SEE ON YOUTUBE

When Yaohua “Betty” Feng watches cooking videos on social media, she often cringes. Well-intentioned food influencers sometimes make suggestions that would never pass muster in a lab, such as microwaving flour to kill salmonella.

“You can kill salmonella if you cook chicken to 165,” she says. “But when it comes to flour, it’s a low-moisture food. The salmonella behaves differently; it’s more heat resistant. We need many more validation studies to determine how to thoroughly heat-treat raw flour at home.”

Watching these videos, and thereby understanding the information home cooks are receiving, is a key part of Feng’s job as an assistant professor of food science and leader of the Food Safety Human Factor Lab.

“We want to try to bridge the gap between ‘How do consumers think every day?’ and ‘How do scientists think every day?’” she says.

Feng has been interested in food safety since she was a teenager growing up in China. Her father ran a seafood processing company, and when Feng was in high school, his company faced a product recall due to heavy metal contamination. “He was really frustrated at that time,” she says. “He didn’t really know why and how to prevent this from happening in the future.”

Wanting to help people like her father, Feng majored in food science. She later worked for a major food corporation, studying consumer perceptions. During PhD study at the University of California, Davis, she combined the two areas.

At Purdue, her lab works with people along the food production chain, from food handlers to consumers, trying to understand their perceptions of risk and figure out the best ways to help educate them on safer practices. Feng's team often works with specific groups — military veteran farmers, for example — to develop targeted food safety materials.

“When it comes to reaching out and changing people’s behavior, the first thing is trying to understand who they are,” Feng says.

To communicate better with consumers, Feng’s lab has helped develop what she calls a dialogue-based curriculum, bringing groups together to discuss and share their food preparation techniques, with a facilitator for encouragement. It’s often more effective to let people learn from each other rather than an expert, Feng says. “In the past we noticed that when it comes to food safety, a lot of people, especially grandparents, think, ‘I have been cooking for many years and no one died in my family, so why should I learn this from you?’”

DATA IS THE FUTURE

These Purdue food safety experts say data will be the future of the field.

“Our college is right on track on promoting and developing more opportunities to share data,” Feng says. “The second step is, ‘How are we going to use this large amount of data to tell a story to support a more robust food safety system?’” To discuss questions like these, Purdue hosted the virtual conference Big Data, Safe Food in 2020.

Deering has been part of a push to make electronic record-keeping easier for farmers. “In the produce world, there’s a ton of papers; farmers still keep papers,” she says. This is problematic for easy information sharing when there’s an outbreak. “We’re getting much better at detecting bacteria, but we’re not really good at talking to each other — state and local health departments, farmers, the FDA. Once we get to the point where more of this stuff is digital, that will be the next big thing. It’s happening, but it’s a slow adoption.”

Ultimately, data is knowledge.

“We are changing people’s knowledge, and how they think about and make decisions around food safety,” Oliver says. “Because almost everything in food safety is preventative.”

- Research, data analysis, education and outreach are all required to keep the food supply safe. Expertise in fields such as chemistry, horticulture, animal science, microbiology, economics and psychology — many of them specialties of the College of Agriculture — is also essential.

- The USAID Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Safety, led by Haley Oliver, 150th Anniversary Professor of Food Science, and her colleague Randy Worobo at Cornell University, leads programs to improve food safety in six countries in Asia and Africa.

- Amanda Deering, associate professor of produce food safety, manages produce safety training at the Purdue Extension Food Safety Training Hub in Southern Indiana, ensuring farmers comply with FDA guidelines.

- Deering also conducts international programs. She helped build a university food technology program in Afghanistan and is working with Peruvian farmers, who find a different kind of food safety when they grow cacao for chocolate instead of coca, the raw ingredient for cocaine.

- Yaohua “Betty” Feng, assistant professor of food science, leads the Food Safety Human Factor Lab, bridging the gap between food safety research and the everyday kitchen practices of consumers.

- Purdue’s food safety experts agree that finding better ways to share food safety data among producers, health departments and the FDA is key to continuing to improve safety in the food supply chain.

Pictured above: Betty Feng led an eye-tracking study to see if participants could find flour-safety messages on 10 different baking mix or flour packages. Her results can help determine whether current labeling is effectively conveying information and changing consumer behavior.

Purdue Agriculture, 615 Mitch Daniels Blvd, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2053 USA, (765) 494-8392

© 2024 The Trustees of Purdue University | An Equal Access/Equal Opportunity University | USDA non-discrimination statement | Integrity Statement | Copyright Complaints | Maintained by Agricultural Communications

Trouble with this page? Disability-related accessibility issue? Please contact us at ag-web-team@purdue.edu so we can help.