the Value Chain

that Circles the Globe

the Value Chain

that Circles the Globe

BY STEVE KOPPES

From the mid-hill region of Nepal in Asia to the southern highlands of Tanzania in East Africa, thousands of smallholder farmers face many of the same challenges. One is how to keep their crops — ginger in Nepal, corn in Tanzania — fresh for months after harvest, so that they can sell some of what they reap under more favorable market conditions. Purdue Agriculture researchers examine every link in the value chain to help make these goals possible.

These scientists are known for their work in crop improvement: creating and testing hybrids that increase yield, resist pests and disease, and withstand drought. Producing plants and animals more efficiently, however, is just one step in the agricultural value chain. Producers have other questions, too: How can I afford land and agricultural inputs without going into too much debt? What are the best ways to store my commodity for later use or sale? How can I protect what I produce from the impacts of climate change?

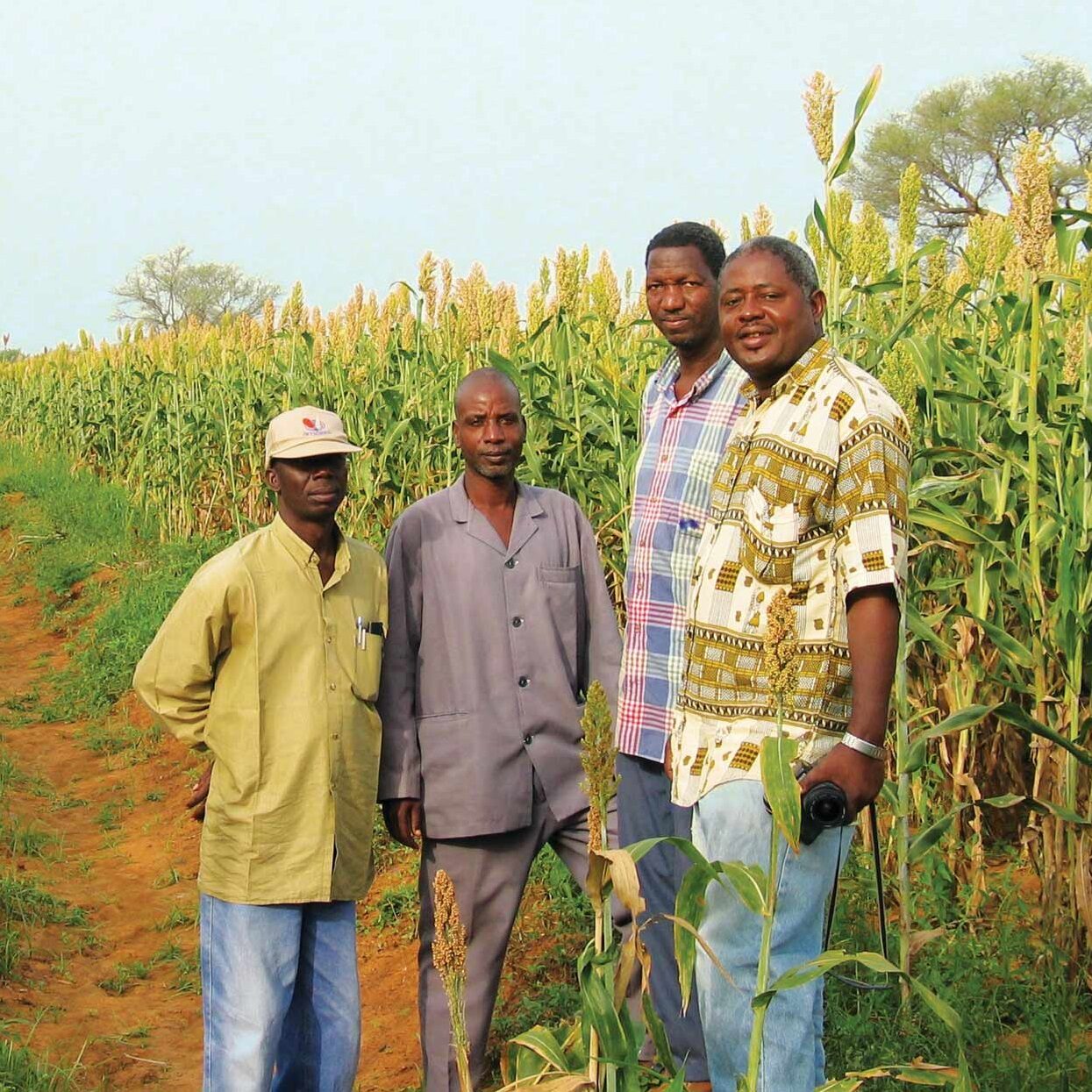

A Purdue team works with local partners to expand access to Purdue Improved Crop Storage bags in Tanzania.

USING LOCAL MATERIALS TO STORE GINGER

A seed grant from the Shah Family Global Innovation Lab launched the Nepal project, led by Julia Bello-Bravo, assistant professor of agricultural sciences education and communication, Gary Burniske, assistant director for program development in International Programs in Agriculture, and Suranjan Panigrahi, professor of electrical and computer engineering technology in the Purdue Polytechnic Institute. The trio partners with Catholic Relief Services; additional support comes from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to scale up the initiative.

A seed grant from the Shah Family Global Innovation Lab launched the Nepal project, led by Julia Bello-Bravo, assistant professor of agricultural sciences education and communication, Gary Burniske, assistant director for program development in International Programs in Agriculture, and Suranjan Panigrahi, professor of electrical and computer engineering technology in the Purdue Polytechnic Institute. The trio partners with Catholic Relief Services; additional support comes from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to scale up the initiative.

Nepal ranks fourth in global ginger production. The spice is widely used in cooking in South Asia and other regions around the world. Compared to many foods, ginger lacks high nutrient levels. “But it does have other health benefits that can help overcome different types of illnesses or prevent them,” Burniske says. These conditions include hypertension, obesity and diabetes.

Bello-Bravo and Burniske base their work in the Palpa District of eastern Nepal. Most of the nation's ginger producers, who are women, must sell their ginger to intermediaries from India soon after harvest. Fresh ginger has a short shelf life, putting growers at a disadvantage.

The ginger farmers plant their produce annually at about the same time, with harvest occurring in late fall. “They flood the market with fresh ginger, and the prices go way down,” Burniske says.

“The intermediaries come and set the price for the farmers,” Bello-Bravo says. “If we find sustainable storage solutions, we can train the farmers to store it and sell the ginger later when the market is not that saturated with fresh ginger. Then they can get more money.”

Effectively grappling with the market-timing issue involves more than simply improving the ginger storage units. “You have to understand the whole value chain from production to marketing,” Burniske says.

Agriculture has become women’s work in Nepal following a high outward migration of young men to the Persian Gulf nations. “Even older men go, and when they go, sometimes they stay out for years,” Burniske says. “Although they do send remittances, the agriculture is handled more and more by women.”

The Purdue team will examine three storage systems that would use local materials to keep ginger fresh without power or water. The types of storage units are unfired clay brick; a shaded, sand-lined pit layered with ginger and sand, capped by a layer of soil; and woven bamboo sheets erected between poles in double layers packed with insulative materials in between.

The systems will need to provide temperature and humidity control. Too much moisture and the ginger will rot or become infected with disease. With too little moisture it will become brittle, lose volume and begin to deteriorate.

Panigrahi, from Purdue Polytechnic, will provide technical assessment of the storage systems. His expertise includes the application of smart sensors to monitor postharvest storage conditions of fresh crops and produce.

Bello-Bravo and her colleagues will also produce an educational animation that addresses the needs of Nepalese ginger farmers. Scientific Animations Without Borders (SAWBO), a Purdue-based educational system that she co-founded and co-directs, has produced 150-plus topic-area videos in more than 300 languages and dialects that over 26 million people have viewed on YouTube.

“We create educational materials in the form of animations translated into local languages and deployed through mobile phones or other electronic devices,” Bello-Bravo says. SAWBO has proven highly effective; for example, a program in Mozambique achieved an 89% solution adoption rate.

“Two years later we went back to follow up. People were still using and sharing the same technique with other people,” she says.

View of Tansen in the Palpa District of eastern Nepal.

View of Tansen in the Palpa District of eastern Nepal.

Julia Bello-Bravo (second from left) talks with a Nepali

family about their needs and constraints in cultivating and harvesting ginger.

Julia Bello-Bravo (second from left) talks with a Nepali family about their needs and constraints in cultivating and harvesting ginger.

FINANCING GRAIN STORAGE IN TANZANIA

In Africa, Dieudonne Baributsa, professor of entomology, leads the CASH-Tz project (expanding Credit Access to Scale-up the use of Hermetic storage in Tanzania). He works with Pee Pee Tanzania Ltd. and other partners to expand the use of Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) technology. The PICS hermetic (airtight) storage bags, developed at Purdue, are a low-cost, simple and effective technology to protect dried crops and foodstuffs from insect pests during storage and eliminate the use of insecticides.

The work to make PICS available and accessible in Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Central America and the Caribbean is ongoing. Now in its third and final year, CASH-Tz provides support to about 20,000 farmers in Tanzania’s Rukwa and Ruvuma regions. Three-way finance agreements already existed between farmers, banks and grain buyers. These agreements provide loans to farmers for inputs such as fertilizer and seed. After harvest, farmers sell their crop to grain buyers and repay their loans to the banks. CASH-Tz taps into this loan cycle to expand PICS bag usage.

“Farmers sell most of their grain at harvest to meet family needs,” Baributsa says. But if they could store their harvested grains for several months, they could sell it at higher prices.

“Unless you maintain the quality of that grain, you cannot sell it later,” he explains, because insects or mold will claim the harvest. Maize weevils and the larger grain borer rank high among Tanzania’s insect problems. In the past, in Tanzania and elsewhere in Africa, banks balked at accepting stored corn and other grains as collateral because of insect spoilage.

“By bringing in effective PICS technology, we are solving the problem of collateral warehouse receipts,” Baributsa says. “The banks have an opportunity to collateralize these grains because there is an effective technology to preserve the quality of that grain, be it against insects or mold.”

PICS protects against fungi-induced aflatoxin infection, too, he notes.

And as in Nepal, women are vital to Tanzanian agriculture. “Women play a big role in managing the stocks,” Baributsa says. “They’re the first to notice whether or not there is damage on the grain that is stored in their house.”

In Africa, Dieudonne Baributsa, professor of entomology, leads the CASH-Tz project (expanding Credit Access to Scale-up the use of Hermetic storage in Tanzania). He works with Pee Pee Tanzania Ltd. and other partners to expand the use of Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) technology. The PICS hermetic (airtight) storage bags, developed at Purdue, are a low-cost, simple and effective technology to protect dried crops and foodstuffs from insect pests during storage and eliminate the use of insecticides.

In Africa, Dieudonne Baributsa, professor of entomology, leads the CASH-Tz project (expanding Credit Access to Scale-up the use of Hermetic storage in Tanzania). He works with Pee Pee Tanzania Ltd. and other partners to expand the use of Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) technology. The PICS hermetic (airtight) storage bags, developed at Purdue, are a low-cost, simple and effective technology to protect dried crops and foodstuffs from insect pests during storage and eliminate the use of insecticides.

The work to make PICS available and accessible in Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Central America and the Caribbean is ongoing. Now in its third and final year, CASH-Tz provides support to about 20,000 farmers in Tanzania’s Rukwa and Ruvuma regions. Three-way finance agreements already existed between farmers, banks and grain buyers. These agreements provide loans to farmers for inputs such as fertilizer and seed. After harvest, farmers sell their crop to grain buyers and repay their loans to the banks. CASH-Tz taps into this loan cycle to expand PICS bag usage.

“Farmers sell most of their grain at harvest to meet family needs,” Baributsa says. But if they could store their harvested grains for several months, they could sell it at higher prices.

“Unless you maintain the quality of that grain, you cannot sell it later,” he explains, because insects or mold will claim the harvest. Maize weevils and the larger grain borer rank high among Tanzania’s insect problems. In the past, in Tanzania and elsewhere in Africa, banks balked at accepting stored corn and other grains as collateral because of insect spoilage.

“By bringing in effective PICS technology, we are solving the problem of collateral warehouse receipts,” Baributsa says. “The banks have an opportunity to collateralize these grains because there is an effective technology to preserve the quality of that grain, be it against insects or mold.”

PICS protects against fungi-induced aflatoxin infection, too, he notes.

And as in Nepal, women are vital to Tanzanian agriculture. “Women play a big role in managing the stocks,” Baributsa says. “They’re the first to notice whether or not there is damage on the grain that is stored in their house.”

IMPROVING SORGHUM IN AFRICA

While some researchers focus on storing crops, others ensure that producers can grow crops worth storing. Tesfaye Mengiste and Mitch Tuinstra work on separate projects making genetic improvements in sorghum, which is broadly used worldwide. In Africa, it’s a staple crop.

Mengiste’s lab specializes in developing crops with fungal resistance because fungi cause most diseases in wheat, sorghum, corn and other plants. He led a team that in 2022 announced the discovery of a gene offering broad resistance in sorghum to several fungal diseases. His team and collaborators also identified sorghum lines with fungal resistance and higher yields that are now available to smallholder farmers in Ethiopia.

“We selected the most important fungal diseases that are as relevant to collaborating countries in East Africa as in the U.S.,” says Mengiste, professor and head of the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology.

With USAID funding, Mengiste and his associates identify the underlying genes in sorghum varieties that show promise for fighting infection. Then they work with growers to move the genes into their preferred varieties.

“The grower may grow a sorghum that has good quality for baking homemade bread, but it lacks that disease-resistance trait. The grower cannot harvest the sorghum because of this,” Mengiste says. “We provide materials. We help them select what they need. We test them and they become released for farmers to grow.”

Such work becomes increasingly important as plant pandemics are likely to come more frequently with climate change.

“There are plant pandemics all over the world. In the U.S. there were significant plant epidemics that caused havoc on corn and other crops. This is likely to occur more frequently,” Mengiste says.

“Somehow the plant environment changes. The plant becomes susceptible. The pathogen becomes more aggressive and virulent. Together, these lead to crop disease epidemics. This is a multidimensional thing,” he says. “In the era of coronaviruses, you ignore microbes at your own peril.”

In 1999, a fungus emerged in Uganda that threatened global wheat production. It spread to Yemen, Iran and other Middle Eastern countries. Hitchhiking pathogens can spread across oceans and continents via hurricanes and other means. “They don’t know political boundaries,” Mengiste says.

Tuinstra, professor of plant breeding and genetics and Wickersham Chair of Excellence in Agricultural Research, works on multiple projects involving corn and sorghum internationally. In West Africa, he focuses on forage sorghum breeding in Niger and sorghum protein quality in Senegal.

“We’ve been working on quality traits of sorghum. We know a lot about the quality attributes of corn but know almost nothing about these characteristics in sorghum,” Tuinstra says. These traits include the quality of forage, grain, starch and protein. Elisabeth Diatta, a visiting scholar in the Department of Agronomy, leads the work on developing the sorghum’s protein quality.

“We have an array of sorghums that are now being released in Senegal to improve the nutritional profile of sorghum for human food,” Tuinstra says. “We’re interacting with food manufacturing companies this year to begin exploring what we do with these new sorghum varieties.”

Some of Tuinstra’s other recent work in Africa was published in a paper in the journal Nature Plants about a tannin molecule that many sorghum varieties have.

“Sorghum is important for people in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Tuinstra says. But he wondered why it has tannin in it: “Tannin is anti-nutritional. It’s bitter.”

His group’s research found that tannin production helps discourage birds from feeding on sorghum. In addition, some African populations have a genetic mutation that prevents them from tasting the tannins. Tuinstra's investigation indicated coevolution among humans, plants and environments.

He also has developed a dhurrin-free sorghum that he patented and commercialized in partnership with Ag Alumni Seed and the S&W Seed Company. Dhurrin can make sorghum poisonous when it breaks down to form prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide) in drought or freezing conditions. Dhurrin-free sorghum is an especially welcome development for farms worldwide that grow sorghum in any hot, dry climate.

MITIGATING CLIMATE CHANGE

Protecting crops and livestock from the impacts of weather can be difficult at the best of times, but climate change introduces an increased risk of extreme weather events. Diane Wang and Luiz Brito lead international research projects that feature robust genetic components to mitigate this risk, focusing on rice and livestock, respectively.

Protecting crops and livestock from the impacts of weather can be difficult at the best of times, but climate change introduces an increased risk of extreme weather events. Diane Wang and Luiz Brito lead international research projects that feature robust genetic components to mitigate this risk, focusing on rice and livestock, respectively.

Wang, assistant professor of agronomy, has two rice-related projects in progress in the Philippines. She developed one of them with Gary Burniske of International Programs in Agriculture, with students participating in the work funded by the National Science Foundation (sidebar above).

And with funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Wang investigates genetic variation underlying rice traits that can help the crop withstand changes in soil moisture. Her partners in this project are scientists at the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines and the USDA Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center in Arkansas.

“Rice is traditionally cultivated in paddies because the standing water suppresses weed growth,” Wang says. But that creates environmental issues because decaying organic material in flooded paddies and standing water produces methane. These issues are compounded by diminishing freshwater resources.

Some rice varieties yield well under alternative wetting and drying (AWD) conditions, a management practice that allows water to partially drain from the fields before flooding them again during the growing season. This practice decreases methane production and water consumption.

Climate change brings more episodes of drought, making it more crucial than ever to produce rice, a globally important crop, with less water, Wang says.

She and her partners are evaluating diverse genetic materials for their performance in drought and AWD conditions. They will test these materials in various environments, including Arkansas, the Philippines and Purdue’s Ag Alumni Seed Controlled Environment Phenotyping Facility.

“Using those data, we’re developing computer simulation models of plant behavior over time to make predictions of how different varieties might perform under new scenarios,” she says.

Livestock also endure the impacts of climate change. Luiz Brito, associate professor of animal sciences, develops precision breeding methods with collaborators in North America, South America and China. Their work helps livestock producers more accurately select animals that have the best traits for their destined climates, whether in Denmark and Norway or Australia and New Zealand. Breeders can, for example, collect DNA samples from pigs or dairy and beef cattle and predict their heat tolerance and disease resilience.

Livestock also endure the impacts of climate change. Luiz Brito, associate professor of animal sciences, develops precision breeding methods with collaborators in North America, South America and China. Their work helps livestock producers more accurately select animals that have the best traits for their destined climates, whether in Denmark and Norway or Australia and New Zealand. Breeders can, for example, collect DNA samples from pigs or dairy and beef cattle and predict their heat tolerance and disease resilience.

A new project will apply precision breeding methods to Peru’s alpaca industry with support from the Arequipa Nexus Institute, a partnership between Purdue and San Agustín National University Arequipa (UNSA).

“We are going to work with alpacas on climatic resilience and also on fiber quality. We are going to develop the same models to help alpaca producers identify which animals will best survive cold temperatures at high altitudes,” Brito says.

Because of climate change in Peru, alpacas tend to forage in the mountains at higher elevations, looking for grass in areas where ice has melted. But cold snaps at these elevations put young alpacas at risk, causing the deaths of about 180,000 of them in 2017 alone.

Brito and UNSA’s Denis Pilares Figueroa will develop precision models to help alpaca breeders identify which of their animals will produce the most climatically resilient offspring. Similar models can help smallholder alpaca producers improve the quality of their fiber, their main source of income.

“If we help them make breeding decisions that will improve fiber quality and the survival of young animals, it will improve their profitability,” Brito says.

The USDA supports most of Brito’s research. “The USDA work is usually done here in the U.S., but it also has implications and applications in other countries,” he says. “Working with people in different countries helps us to improve what we do at home as well.”

- Research abroad helps improve agricultural products and practices around the globe while also benefiting the U.S. through the introduction of new practices and improved commodities.

- Women are the primary producers of specific crops in Nepal, Africa and many other cultures.

- Smallholder farms in Nepal and Tanzania need better storage systems to preserve their crops, allowing farmers to sell for higher market prices during the offseason.

- Plant diseases do not recognize borders as they spread and ravage crops globally, emphasizing the need for international collaboration to protect the harvest at home and abroad.

- Genetic improvements to crops and livestock alike can help mitigate harmful climate-change impacts.

- Students from Purdue and minority-serving institutions gain international undergraduate research experience in the Philippines with National Science Foundation support.