One in six Americans becomes sick from foodborne illness every year. While the U.S. food system is one of the safest in the world, foodborne illness is still costly. Health costs and productivity losses from foodborne illness cost the U.S. economy $17.6 billion per year. Food safety risks from consuming these items can often be mitigated, but consumers can also reduce the risk of contamination through safe food-handling practices.

A recent study from our team using Consumer Food Insights data, quantified consumer adoption of a few safe food-handling practices and explored how risk perceptions and risk preferences influence behavior. Risk preferences refer to how much risk a person is willing to take given an expected outcome. Risk perceptions are a consumer’s subjective judgment of a risk or threat.

We measured consumer risk preferences and perceptions and evaluated how these correlate with consumers’ risky decisions related to food, specifically eating unwashed leafy greens, rare meat and raw dough.

We focused on products and practices that are associated with Escherichia coli (E. coli), one of the leading foodborne pathogens. When it comes to E. coli, leafy greens, rare meat and raw dough are commonly linked to food safety concerns and recalls. Of the three reported E. coli outbreaks in 2022, ground beef was the responsible culprit for one of them and in 2021, two of the four E. coli outbreaks were caused by leafy greens. Since 2016, three reported E. coli O157 outbreaks resulted from flour or cake mix, flour often being the culprit of contamination in “raw dough.”

We asked participants responding to our survey a set of questions designed to measure consumer risk aversion and risk perceptions associated with three food behaviors commonly connected with foodborne illness. Respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements about the risk of each food behavior on a scale from 1-strongly disagree to 9-strongly agree. In the case of raw batter or dough, respondents were shown the following statement: “eating raw dough or batter poses risks to me and my family.” Respondents were split into three groups based on their responses on the risk perception scale: low (1-3), moderate (5-6) and strong (7-9). We then asked consumers the frequency with which they participate in each of these three risky food behaviors. When it comes to risk attitudes, we found that the average consumer is risk averse, and only 10% of respondents are risk-seeking.

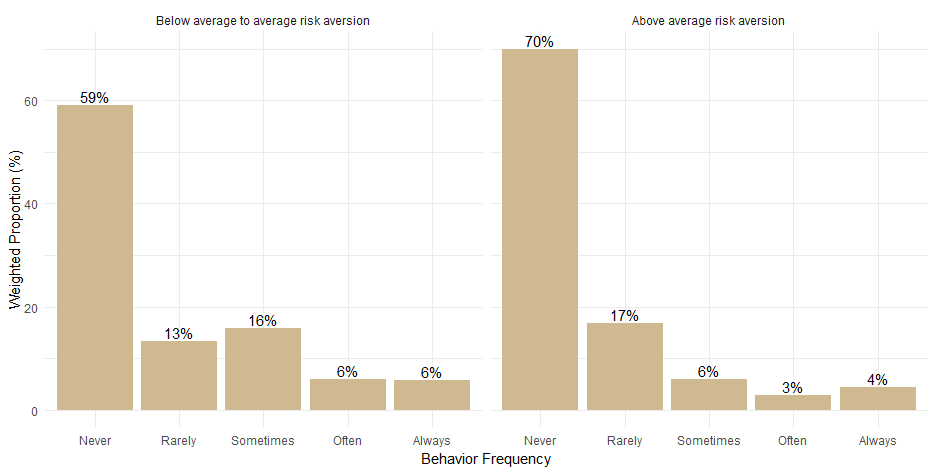

In Figure 1 below, we show the relationship between behavior (i.e., frequency of consuming raw cookie dough) and risk preferences. On the left we show frequencies for those with low (below average) risk aversion, and on the right frequencies for those with relatively high (above average) risk aversion. (Data for eating unwashed leafy greens and rare or undercooked meat follow a similar pattern.)

Most survey respondents shared that they “never” or “rarely” engage in consuming raw dough or batter. Comparing less risk averse consumers (left) to more risk averse consumers (right), 32% of consumers with below-average risk aversion said they sometimes, often, or always eat cookie dough, compared to 13% of consumers with above-average risk aversion. That is, we find that, as expected, consumers who are less risk-averse are more likely to consume foods that are known to pose a risk to their health.

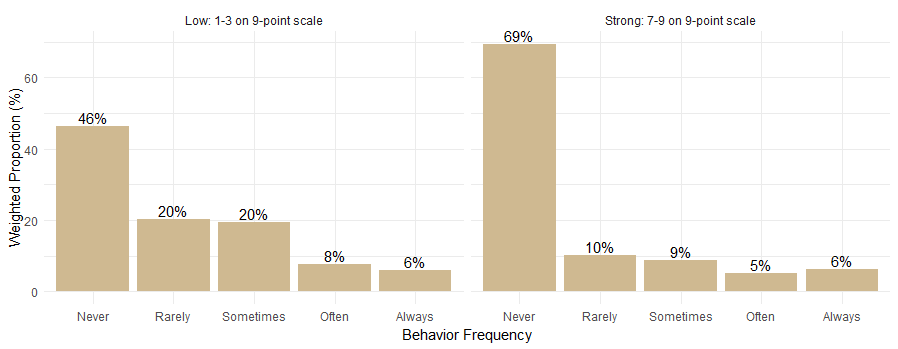

In Figure 2, we present the frequency of consuming raw cookie dough for people who perceive low and high risk of foodborne illness. We observed a significant difference when comparing the reported behavior frequency of those with ‘strong’ risk perceptions with ‘low’ risk perceptions. Unsurprisingly, consumers who perceived the risk of eating raw dough or batter as strong were less likely to engage in the risky food behavior, while those who responded lower on the scale, indicating lower risk aversion, reported engaging in the behavior more frequently. There is over a 20 percentage-point difference in the number of respondents who ‘never’ eat raw dough or batter when comparing the ‘low’ risk group and the ‘strong’ risk group.

So, what new insights do our findings provide? Our data confirm the economic intuition on how risk attitudes and risk perceptions influence food behaviors. Specifically, consumers who exhibit higher levels of risk aversion are less likely to consume raw dough.

We also observed that individuals’ risk perception is associated with their subjective assessment of the risk involved with the behavior. Those participants who perceive a higher risk associated with consuming raw dough or batter are less likely to do so.

One potential policy implication from this work is that public health authorities may be able to influence behavior by communicating the risks. If consumers underestimate the risk associated with eating raw dough, information campaigns that align the subjective risk evaluations with true risk may reduce the incidence of foodborne illness.

There are still unanswered questions about consuming raw meat, leafy greens and raw dough. More research can be done to understand how risk perceptions align with what food safety experts deem to be the risk associated with consuming such products. The bottom line is that consumers have varying sensitivity to risk that relates to the food choices they make.

Visit the Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) website for helpful tips on food safety practices and preventing foodborne illnesses.

For questions and/or inquiries related to this topic, you can contact us through this form or email chubbell@purdue.edu.

Footnotes:

- We observe a similar distribution with the other two food behaviors, eating unwashed leafy greens and raw dough.

- In work not discussed in this post, we found a statistically significant inverse relationship between relative risk aversion and the frequency of consuming raw cookie dough.