Pesticide Minibulks

Fred Whitford

Director, Purdue Pesticide Programs

Joe Becovitz

Pesticide Program Specialist, Office of Indiana State Chemist

John Obermeyer

Integrated Pest Management Specialist, Purdue University

Mike Titus

Safety and Risk Coordinator, Co-Alliance

Julie Lamberson

Risk Manager, Harvest Land Co-op

Kip Landwehr

EHS Manager, Winfield United

Kevin Leigh Smith

Continuing Lecturer and Communication Specialist,

Purdue Agricultural Sciences Education and Communication

Understanding ‘Bulk’ and ‘Minibulk’ ………………………………………6

Secondary Containment Regulations for Farms and Retailers ………. 1 0

Requirements for Filling Minibulks……………………………………….14

Pressure Testing Minibulks………………………………………………. 21

Farm-Owned Minibulks…………………………………………………… 24

Conclusions………………………………………………………………..28

Acknowledgements……………………………………………………….30

Disclaimer …………………………………………………………………. 31

LEFT OF 4

Minibulks — also referred to as shuttles, totes, or intermediate bulk containers — are routinely used to safely transport thousands of gallons of pesticides, fertilizers, and adjuvants between retailers and farms. They have become an irreplaceable part of agricultural operations.

Minibulks provide quantifiable advantages to both the retailer and the farmer, including the following:

Bulk pricing — retailers that order pesticides in bulk quantities receive significant price discounts from manufacturers. In turn, the retailers can pass those discounts on to their farmer customers. This is especially important when you consider that a 2.5-gallon container typically costs much more than the same material purchased in bulk.

Bulk storage — If used correctly, minibulks allow farmers to utilize the benefits of buying in bulk without building costly permanent bulk storage facilities.

Return for credit — farmers could possibly return any unused product left in minibulks to their retailers if the tank’s seals remain intact and the retailers accept bulk returns.

Reduces plastic — minibulks can replace hundreds of smaller plastic containers, which can save a significant amount of time and money. For instance, one 250-gallon shuttle will replace opening, pouring, rinsing, and disposing of 100 2.5-gallon containers.

Refillable — retailers can fill and refill minibulks many times over their lifespan. Compare this to the cardboard and plastic waste generated from single-use, and 1- and 2.5-gallon containers.

Fewer injuries — applicators can dramatically reduce their pesticide exposure when they can pump product from minibulks directly into their sprayers. Pouring out of containers requires repeated climbs up and down the sprayer, which increases the potential for slips and falls.

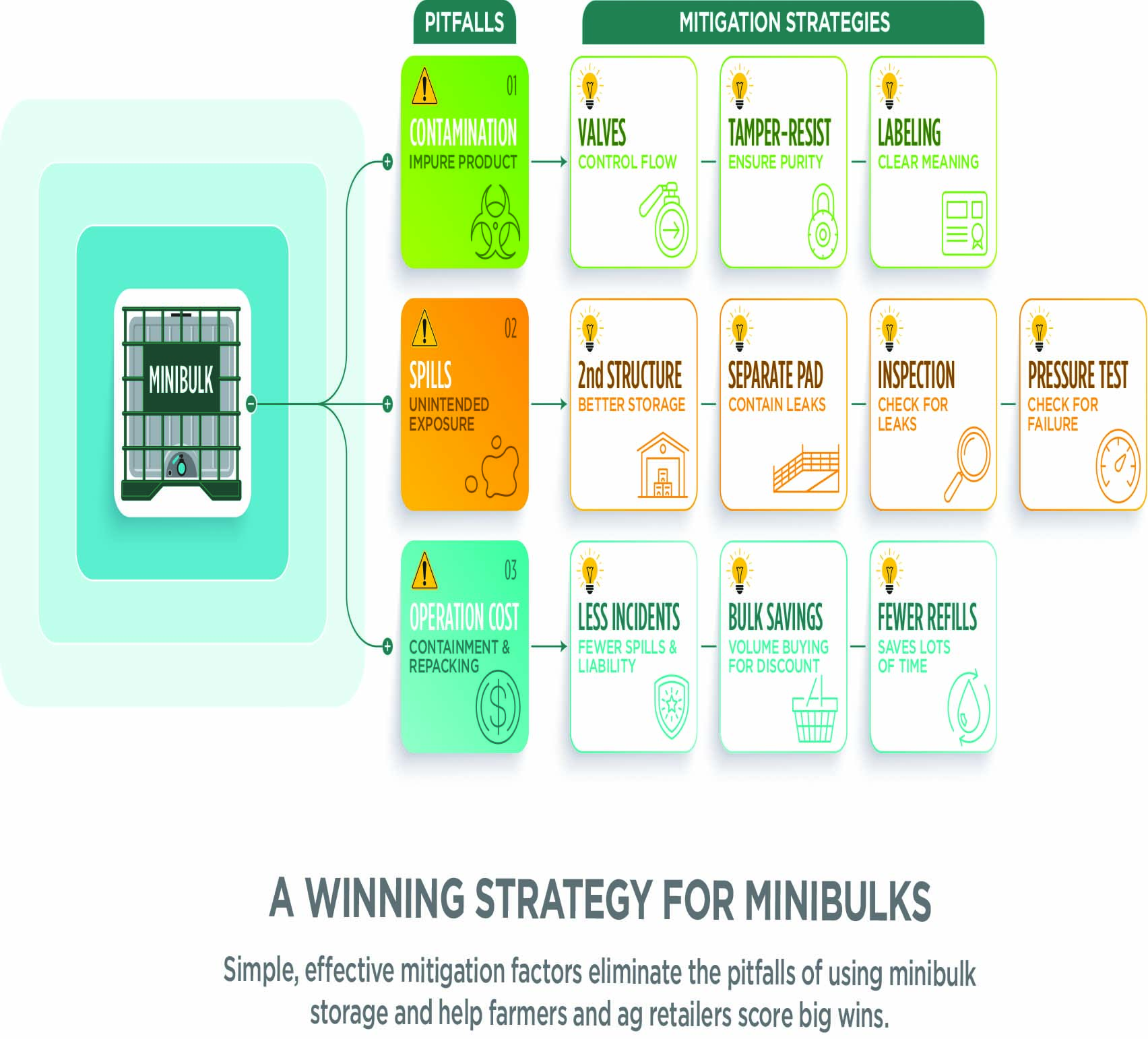

Despite these advantages, there are also legitimate concerns when using minibulks. Larger containers can mean bigger problems during transport, storage, and use. In fact, most minibulk spills occur during the loading, transporting, or unloading of the container. A minibulk spill can mean hundreds of gallons on the ground (which can then potentially move to environmentally sensitive sites) instead of just 1 or 2 gallons from a jug.

In addition to transportation concerns, there are rules governing the filling and storage of bulk and minibulk pesticide containers. These rules are administered and enforced by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), and Office of Indiana State Chemist (OISC).

This publication provides farmers and retailers guidance and best practices for managing, storing, handling, and transporting pesticide minibulks.

Understanding ‘Bulk’ and ‘Minibulk’

We often use terms like “bulk” and “minibulk” without much thought; however, the regulations clearly identify the exact meaning of each.

The OISC and EPA define liquid bulk pesticide as an undivided quantity greater than 55 gallons. This definition is different than the DOT’s, which is 119 gallons for hazardous materials. By default, 55-gallon drums and 2.5-gallon containers are not considered bulk pesticides.

This distinction is more than a little important. Indiana pesticide regulations are based on understanding this definition.

There are two types of bulk pesticide storage tanks: larger stationary storage tanks and smaller minibulks.

Stationary storage tanks are generally constructed of stainless steel for durability and ease of cleaning. They hold between 400 and 5,000 gallons. These tanks require secondary containment — see Bulk Pesticide and Fertilizer Storage on Indiana Farms (Purdue Extension publication PPP-63, available at edustore.purdue.edu and ppp.purdue.edu).

In addition, stationary tanks are usually equipped with dedicated plumbing. The dedicated plumbing is used to fill minibulks and sprayers and helps to significantly reduce cross-contamination by keeping products separate from one another. Stationary pesticide tanks (unlike bulk fertilizer tanks) are usually stored under roof.

State and federal regulations define smaller minibulks as tanks with a capacity of more than 55 gallons but not exceeding 400 gallons. Most minibulks in use today are somewhat standardized and hold roughly 110, 125, or 265 gallons (tank capacities of 120, 135, and 275 gallons, respectively). Minibulks may arrive at the retailer already filled by manufacturers, or they may be refilled from the retailer’s bulk tanks. Retailers often store minibulks in the same heated contained buildings as their stationary bulk tanks.

Minibulks are designed to be mobile, shuttling product to the farm or field where users can transfer the material directly to sprayers. Farmers and retailers also place minibulks on trailers along with water and other supplies. The trailers become mobile mixing sites and can easily follow sprayers from one field to the next.

At one time, minibulks came in dozens of shapes and colors. It was easy to identify a particular pesticide product based on the shape, color, and size of the container.

Today, most manufacturers place their products in caged plastic tanks. Cage tanks are basically nondescript molded plastic tanks that have supporting steel or aluminum shells around them and bladders inside the cage.

Secondary Containment Regulations for Farms and Retailers

Although minibulks are sometimes used for semi-permanent storage, they are really designed to be mobile containers that can be filled, emptied, and refilled quickly. If used the way they are intended (as temporary storage), then the regulations state that minibulks that are stored or used at retailers or farms for 30 days or less do not require secondary containment.

For prefilled minibulks delivered to retailers or farms, the 30-day period starts on the day of delivery. For retailers that refill minibulks, the 30-day period starts on the day the minibulk is filled. If OISC inspects a facility, it is likely the facility that’s being inspected (whether farm or retail) will have to furnish proof of date filled or date delivered.

Different Rules Apply to Fertilizers

The requirements for storing bulk pesticides and fertilizers are different. Regulations for bulk fertilizer storage start when quantities exceed 7,500 gallons or a single tank holds more than 2,500 gallons.

See Bulk Pesticide and Fertilizer Storage on Indiana Farms (Purdue Extension

publication PPP-63), available at edustore.purdue.edu and ppp.purdue.edu.

Minibulks stored at the farm or retailer for more than 30 days must be in secondary containment. There are a few secondary containment options for storing minibulks.

These options can include:

- Storing minibulks within an existing secondary containment structure. Minibulks cannot be stored in fertilizer containment unless separated by a wall.

- Using an already existing 10-foot x 20-foot mix/load pad, which is sometimes referred to as operational area containment.

- Building a separate 10-foot x 20-foot sloped pad that holds a minimum of 750 gallons. The pad needs to slope toward a sealed sump that allows users to recover material from a ruptured minibulk.

Requirements for Filling Minibulks

Federal regulations spell out specific requirements that dealers must comply with when they take product from stationary bulk tanks to fill minibulks.

EPA Registration

According to the regulations, any facility that “produces” a pesticide product is required to register with EPA as a pesticide-producing establishment. Production can mean that the facility mixes ingredients according to a labeled formula to make a pesticide product. Or, as is usually the case with ag retailers, production can mean simply transferring pesticide product from one container to another for the purpose of resale. All pesticide-producing establishments must report their production (even zero production) to the EPA by March 1 of the following year.

Repackaging Agreements

Retailers must have repackaging agreements from each manufacturer to repackage bulk pesticide products. Retailers must make copies of current agreements available for inspection by the OISC at each repackaging location. The written contracts lay out exactly what products ag retailers can repackage, what containers the products can be repackaged in, how and when to clean minibulks, and inspection protocols.

Unique ID

Whenever users refill or repackage minibulks, they must mark each one with a unique ID or serial number.

However, minibulks obtained directly from manufacturers and shipped to customers do not require unique serial numbers. If farmers bring minibulks back to retailers for refilling, all of the repack agreement requirements kick-in,

including assigning the shuttle an ID number.

Do Rules Apply to Farmers?

Do farmers with their own bulk tanks have to follow the same requirements

as ag retailers?

Farmers who store bulk pesticides for their own use, are considered end users.

Under this use, farmers are not subject to EPA’s bulk repacking regulations.

However, if a farmer acts as a retailer and sells minibulks to other growers,

then that farmer now falls within the full scope of the repackaging regulations.

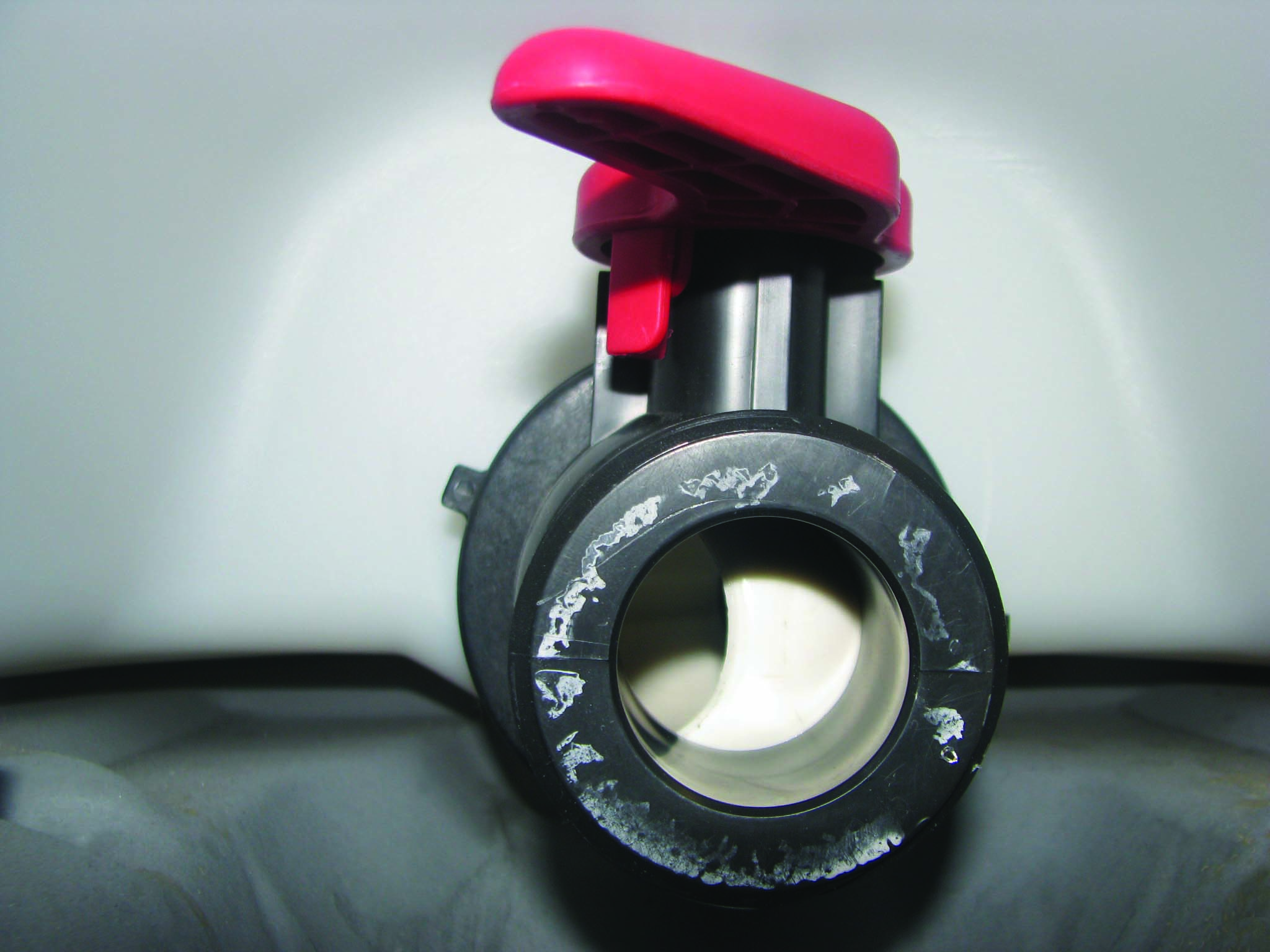

One-way Valves

Refillable minibulks must have one-way valves that only allow product to flow out of the tank.

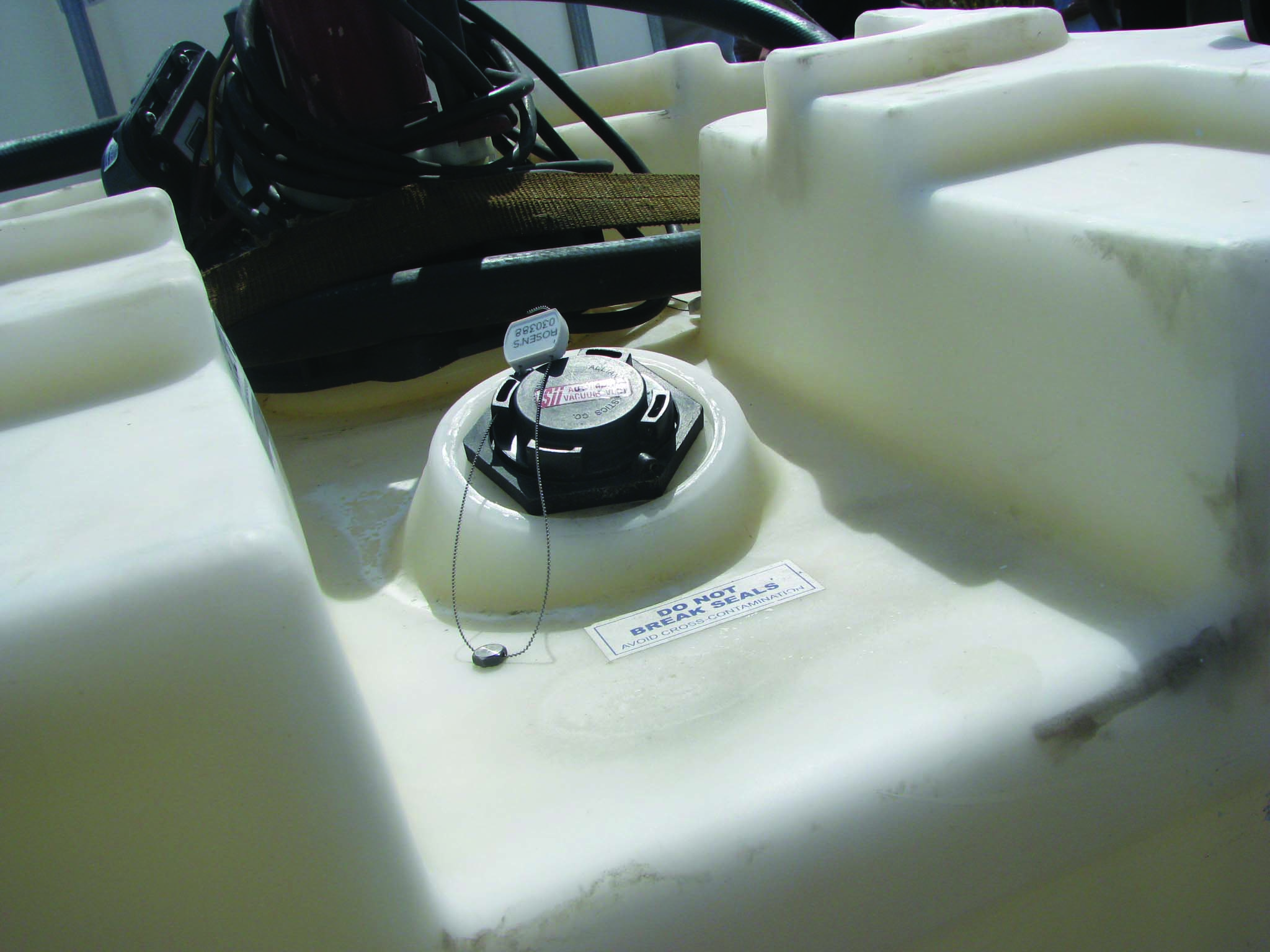

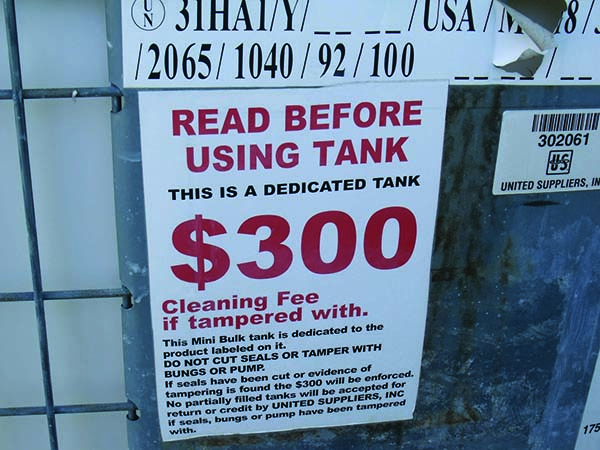

Tamper-evident Seals

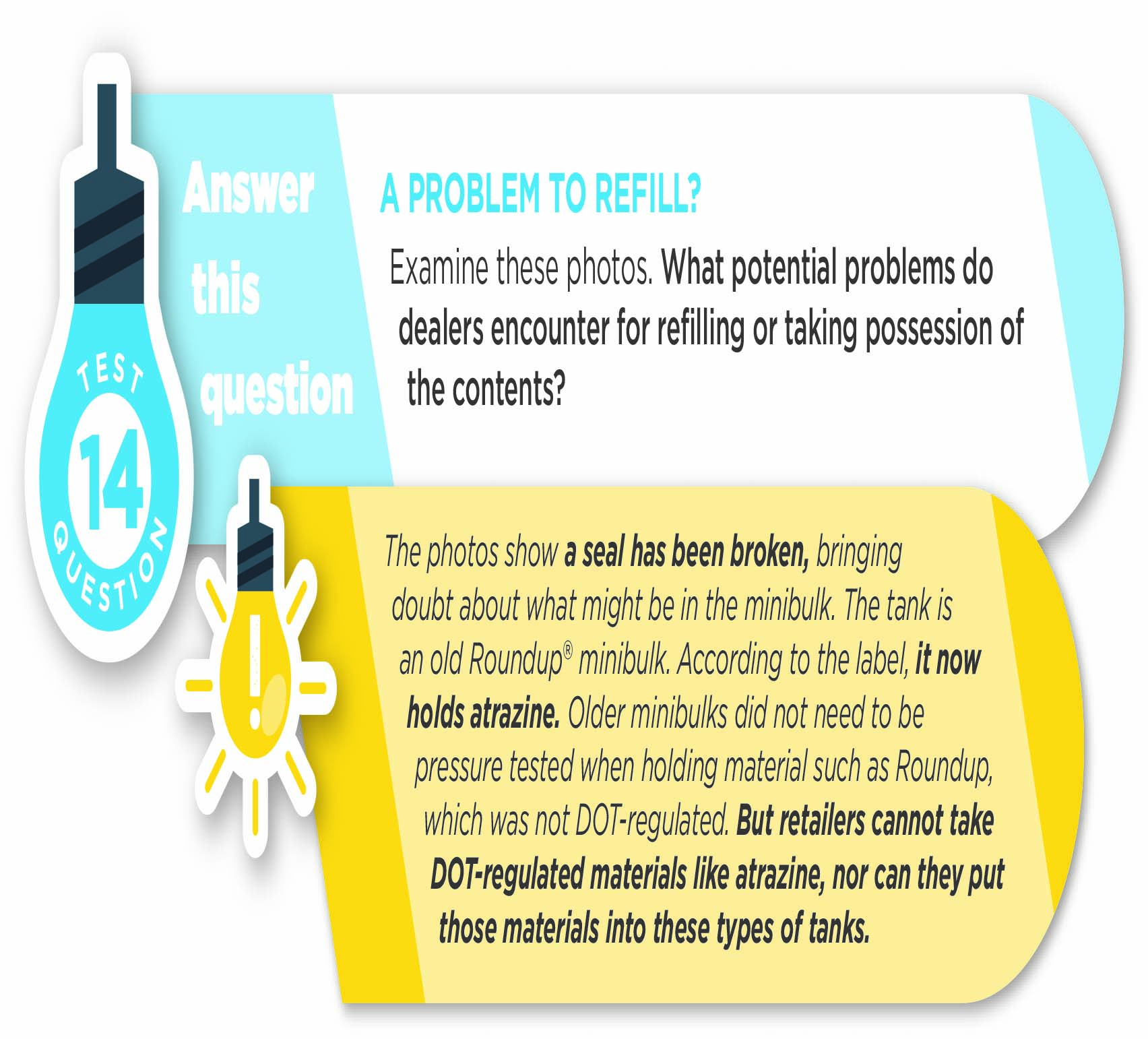

Retailers and manufacturers must place tamper-evident seals on or around openings before they ship minibulks. These external seals provide important visual clues when users return minibulks. The seals help protect the product’s integrity while in service. If the seals are intact, the product in the tank has not been tampered with. If any of the seals are broken, retailers must follow the specific cleaning instructions found in their repackaging agreements before they can refill the minibulks — even if they refill minibulks with the same product.

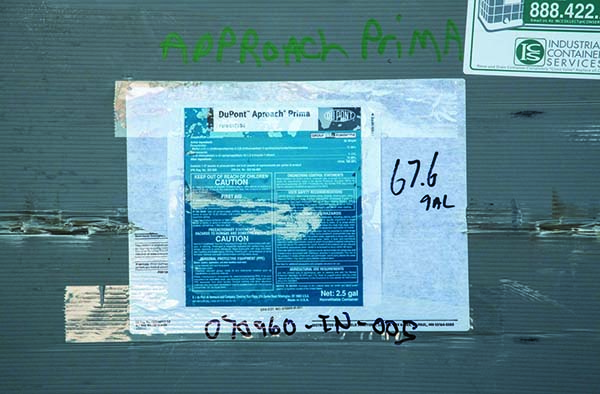

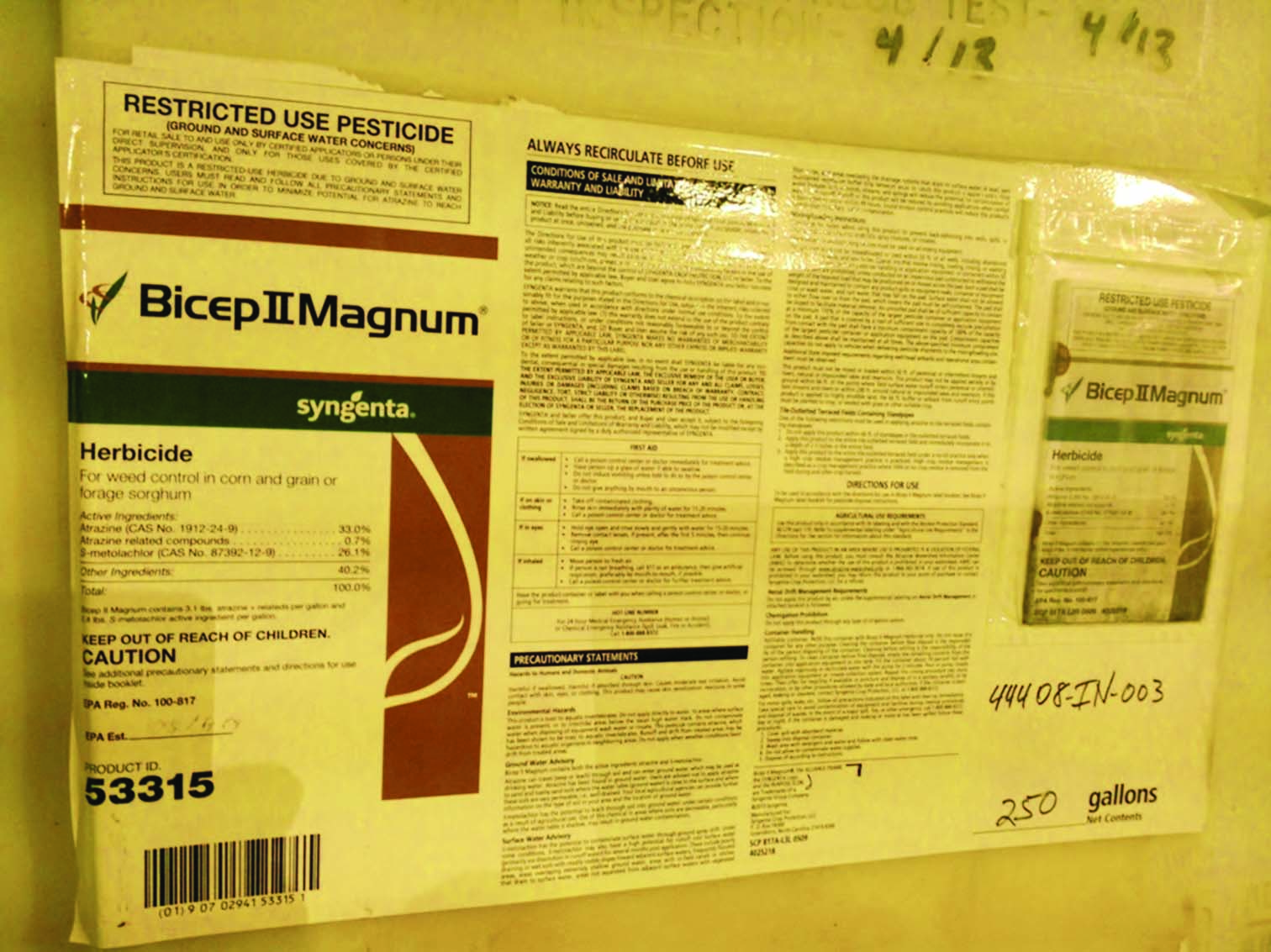

New Labels

Attach new labels to minibulks each time you fill them. The labels should include the EPA establishment number and net contents. The establishment number on the minibulk is the same one the EPA assigned to the facility. This holds true even if a facility fills a minibulk for a “sister” facility. The establishment number written on a minibulk is always the number for the location where the container is filled.

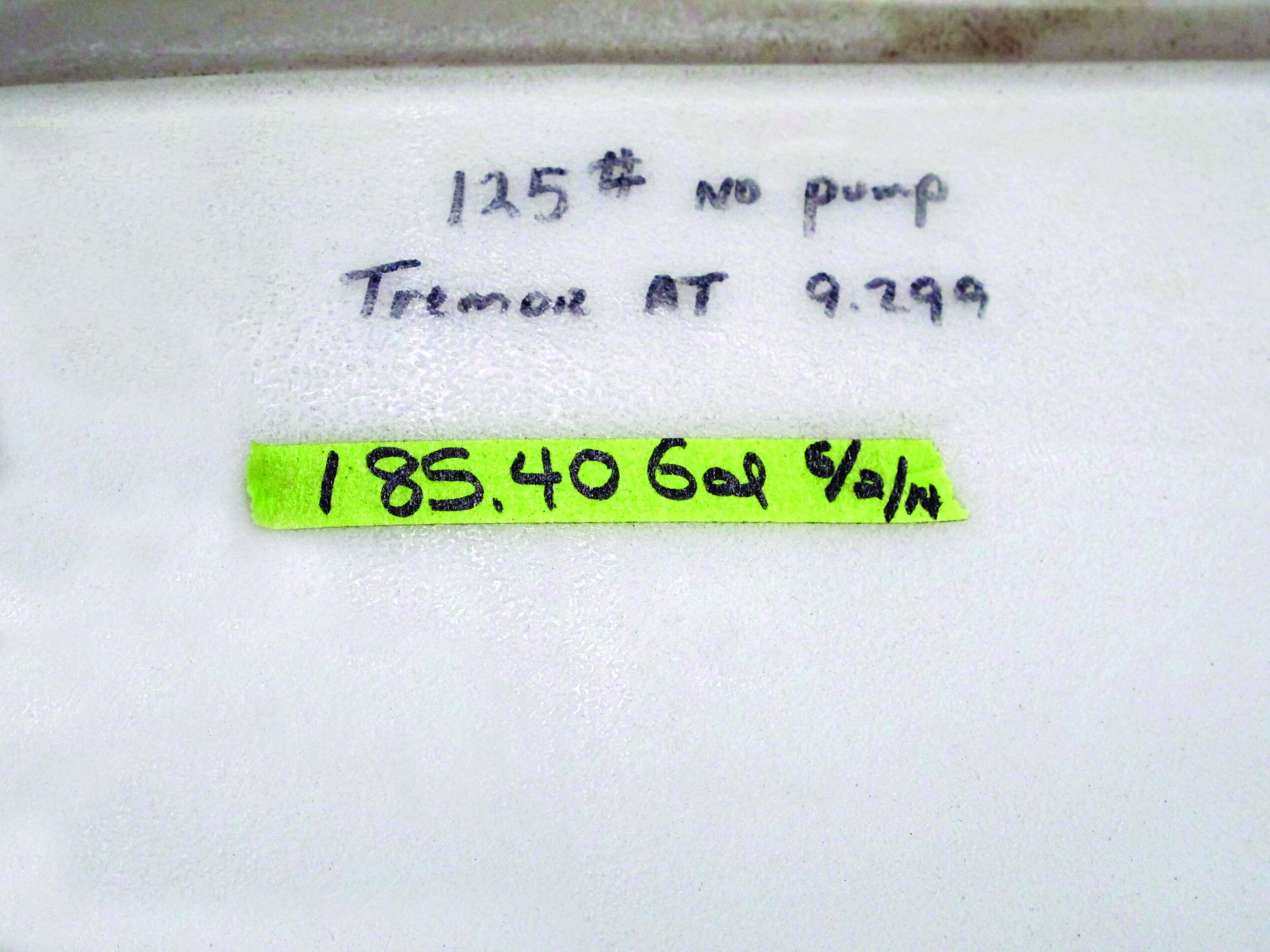

It is important to note that the tank’s net contents are not the same as the tank’s capacity. The net contents are the amount of product that was put into the tank at refilling. For example, let’s say a customer brought back a 250-gallon tank to the retailer for refilling. There were 50 gallons remaining in the tank when the customer brought it in. The dealer put 200 gallons in the tank.

The net contents written on the label would be 200 gallons, not 250 gallons. Although not required, some dealers also include the date the minibulk was refilled on each label.

Record Keeping

Each time retailers fill containers, they must record the unique ID numbers, dates, and EPA registration numbers for the products. Retailers must keep these production records for three years. If the product is a restricted-use pesticide (RUP), then retailers must keep an additional, more detailed record of sale or application for two years. Each year, retailers must submit a summary of all pesticide production (amounts filled for each bulk pesticide product) to the EPA.

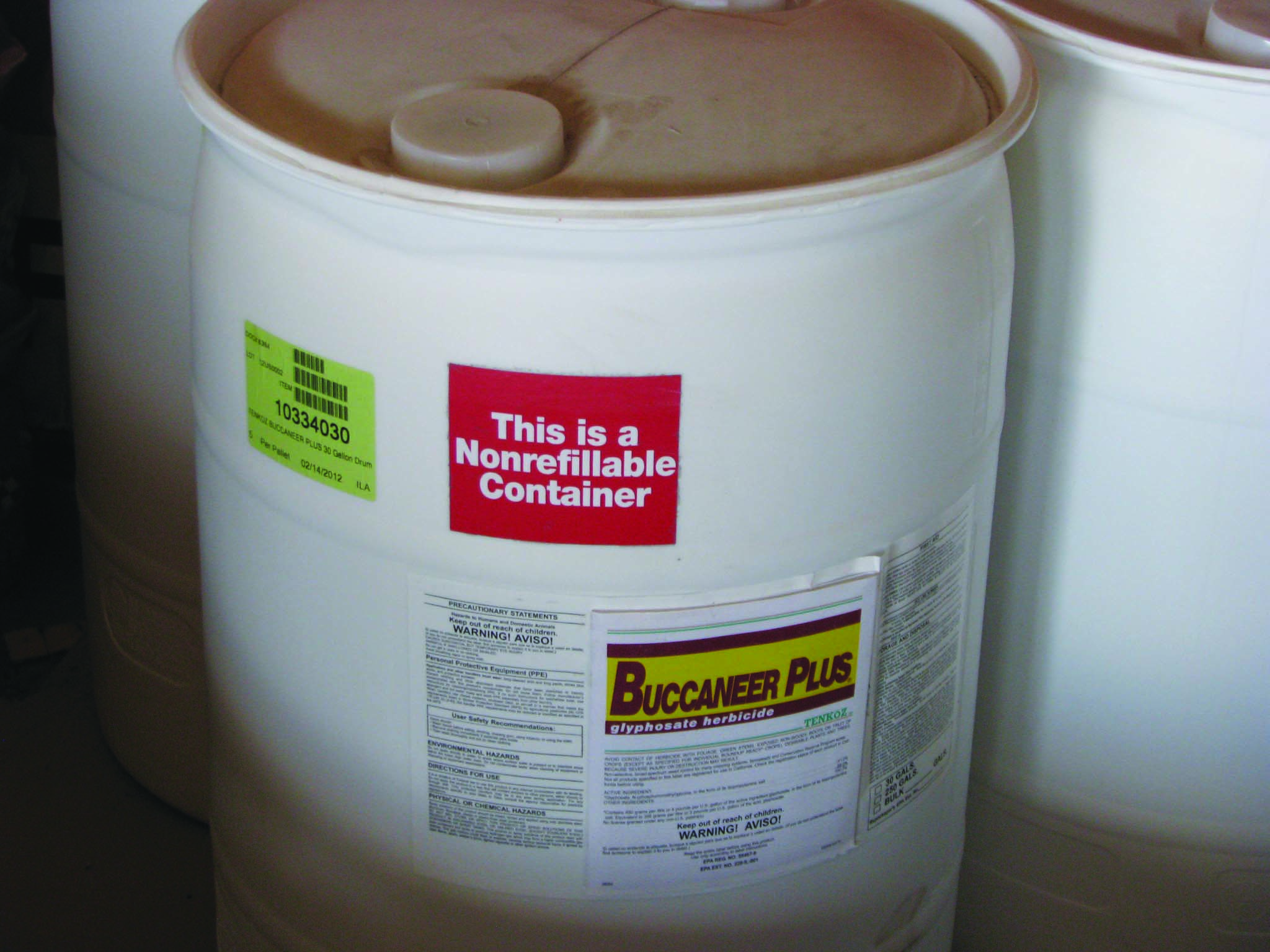

Inspection and Cleaning Requirements

Retailers must determine if minibulks can be refilled by reviewing the tank labels to see if they are marked as refillable or non-refillable. Since most minibulks are meant to be reused, inspecting them is perhaps the most

important part of the refilling process.

Proper inspections can reveal faulty containers, leaking valves, tanks that need to be recertified (pressure-tested), or contamination issues. Failing to inspect returned containers before refilling them can result in contamination issues, which may cause thousands of dollars in unintentional crop damage and ruined reputations.

When you inspect minibulks:

• Ensure that all valves are functioning.

• Examine the outside of the tank for any spills, leaks, or cracks.

• Examine the pesticide label on the outside of the tank and all tamper-evident seals to ensure they are intact. If the tank labels do not match the product about to be put into them, or if any seal is cut or broken, then retailers must clean the minibulks according to the instructions in the repack agreement. They must clean the tanks over a wash pad where they can collect the rinse water.

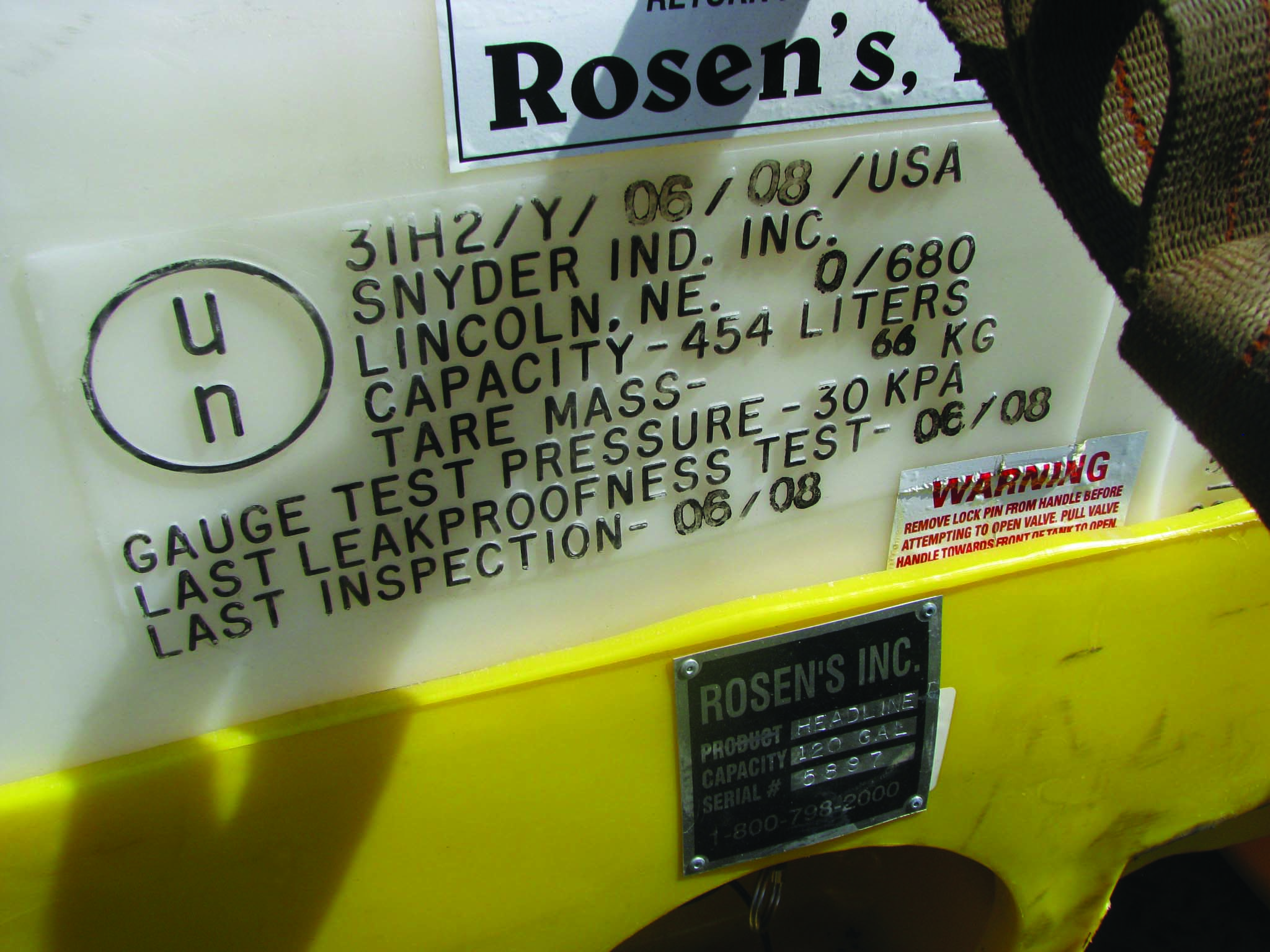

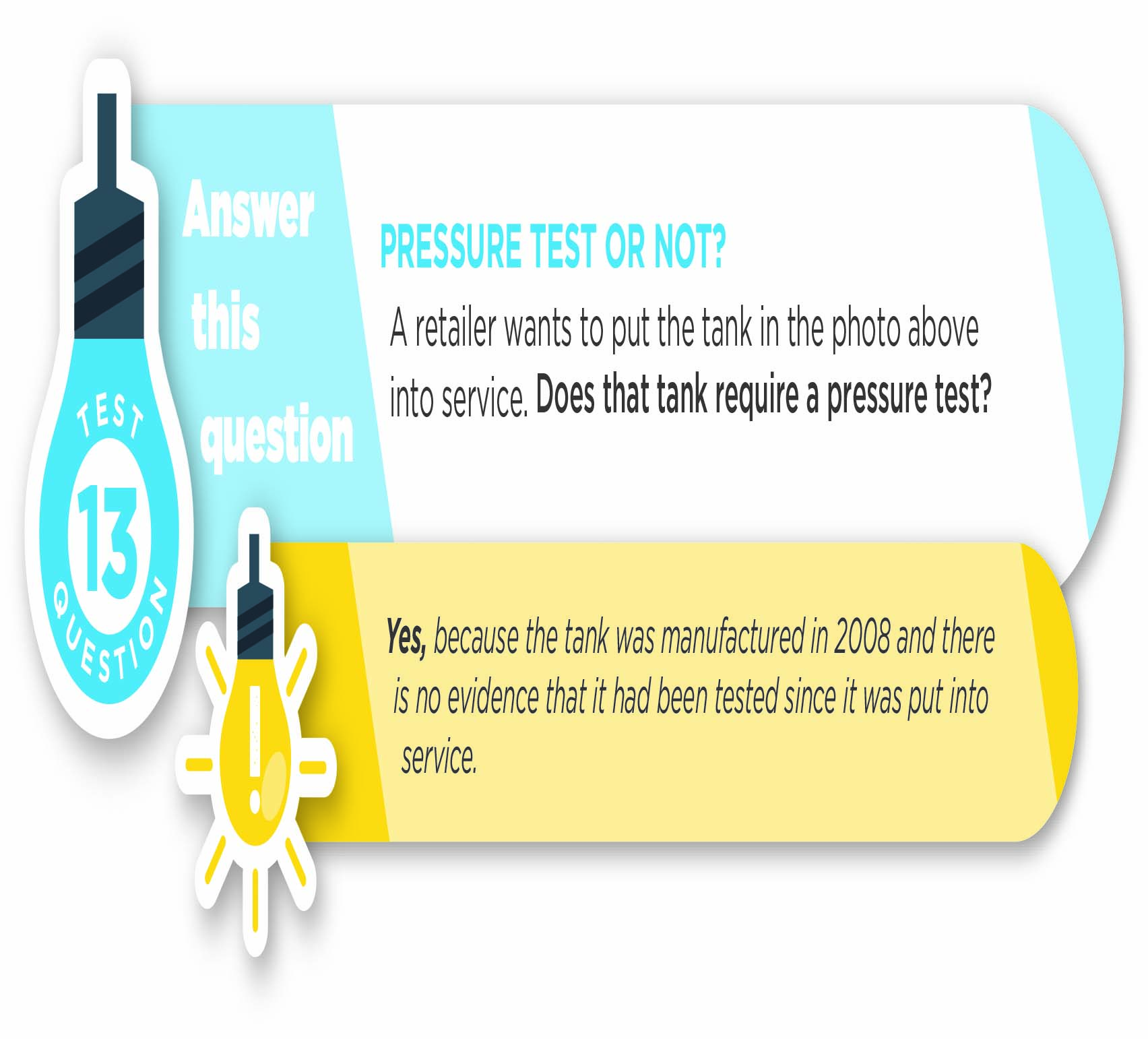

Pressure Testing Minibulks

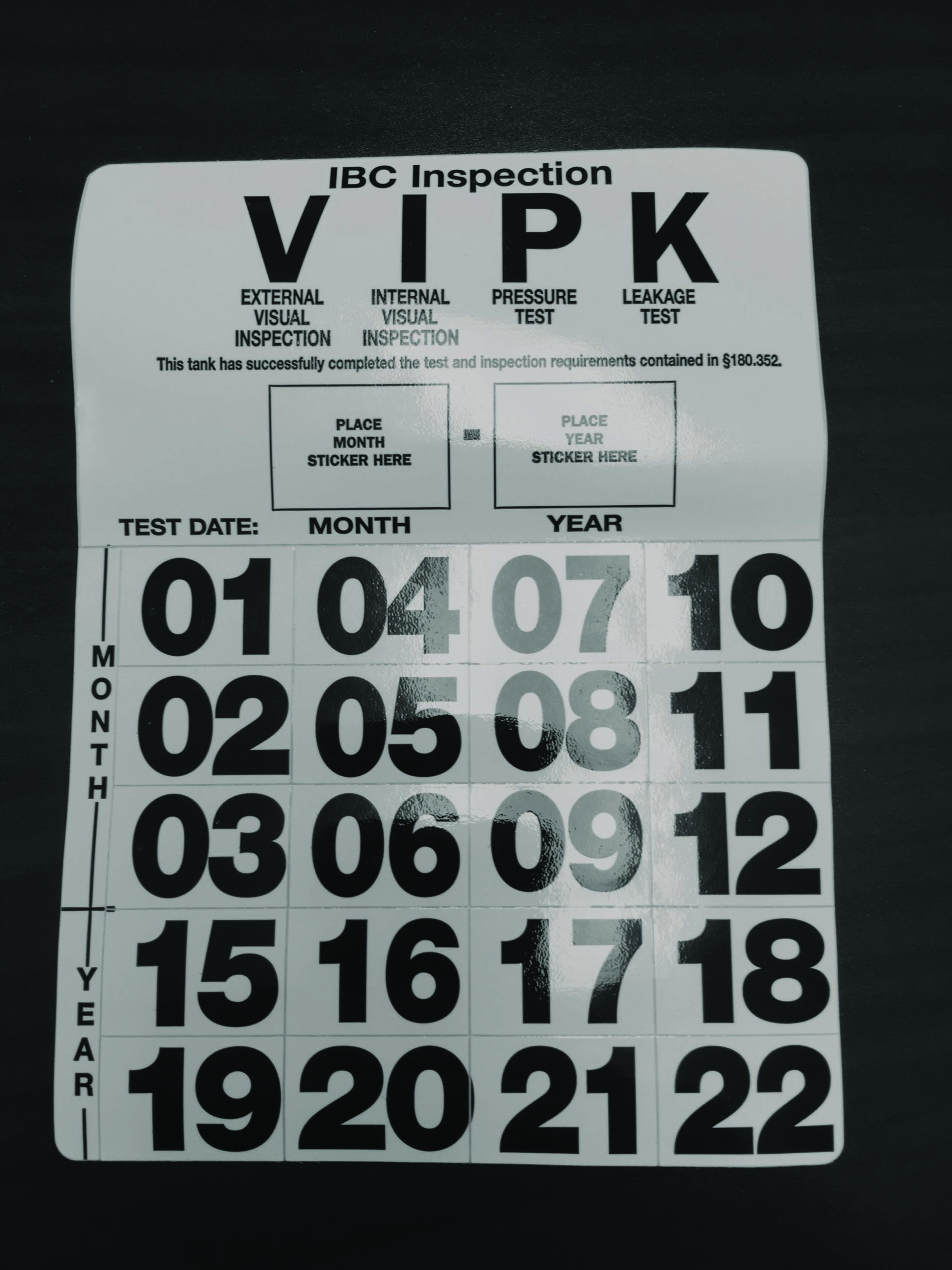

EPA regulations defer to the United States Department of Transportation (DOT) when it comes to testing the integrity of minibulks. DOT requires pesticide manufacturers to build their shuttles to specific standards that depend on the classification of the pesticides they will transport. DOT regulations require that some, but not all, minibulks used to transport pesticides must be pressure tested every 2.5 years or 30 months.

For the purpose of this publication we have arbitrarily sorted minibulks into four major categories under DOT rules:

- Minibulks that hold materials not classified by DOT. While some of these containers are still in use, these tanks were some of the first minibulks to be used, and did not require pressure testing. These older minibulks include green and white shuttles for glyphosate-based herbicides.

2. Single use, nonrefillable tanks. These tanks are more commonly used for adjuvants. Pesticides are seldom packaged in one-way shuttles. Since these are one-way, disposable tanks, they do not require pressure testing. Check labels to confirm tanks are non-refillable.

3. Limited refillable and reusable minibulk tanks. Refillable minibulk tanks (or cage tanks) are containers that the retailer will dispose of at the end of 2.5 years. Consequently, these tanks do not require pressure testing.

4. Long-term, refillable, and reusable minibulk tanks. These are the tanks that require pressure testing every 2.5 years. Check labels to confirm tanks are refillable.

One of the quickest ways to determine if a minibulk requires pressure testing is to look at the UN code assigned and affixed to the minibulk. The testing requirements for any tank are based on the UN specification mark on the

tank itself.

The specifications include the UN symbol:

UN containers have an X, Y, or Z marked on the tank. Refillable UN containers require pressure testing every 2.5 years.

At a minimum, employees who pressure-test minibulks should wear eye protection, but be sure to follow label directions relative to personal protective equipment.

To begin the pressure test, make sure that all openings (like caps, one-way valves, and vents) are completely closed. Pressurize the container to 3 psi and wait 5 minutes to see if the tank maintains pressure. The pressure added to the tank may cause the container to slightly bulge out. Do not apply too much pressure — that can permanently damage the container and/or injure the tester.

If a tank does not maintain the pressure, it means there is a leak. Take either soapy water or glass cleaner and spray it around the lids, valves, and other areas to pinpoint the leak’s source. The solution will bubble up, revealing the exact location of the leak. Repairing leaks is often as easy as replacing an O-ring in a cap or tightening a loose valve.

These photos show a tank with almost 2 psi. “We stopped the test, because the two metal straps on top were about to break,” the operator said. Always use caution when pressure testing cages!

If the container holds 3 psi for 5 minutes with no signs of leaks, then it has passed the pressure test. Permanently mark the month and year of the inspection on the container near the UN marking.

In addition, you must create a record to document the testing protocols. These documents must be kept for three years.

That documentation must include:

- Tester’s name

- Name and address of the testing site

- Date of the test

- The container’s identification number based on its serial number or another number permanently marked on the tank

- Conclusion statement of pass or fail

- Description of the testing procedure used

There are times when tanks fail pressure tests and must be taken out of service. When that happens, permanently and prominently mark the minibulk as “Out of Service” or “Failed Pressure Test.” Make sure to note in your records when you took a container out of service, and then destroyed or recycled it. The Pesticide Stewardship Alliance lists minibulk recyclers on their website: tpsalliance.org/mini-bulk-ibcmgmt/container-collection-and-recycling-resources.

Farm-Owned Minibulks

As end users, farmers are not required to follow the same production rules as ag retailers. This means you can transfer material for your own use from a retailer’s minibulk into your own minibulk without worrying about production reports, UN codes, or even pressure testing.

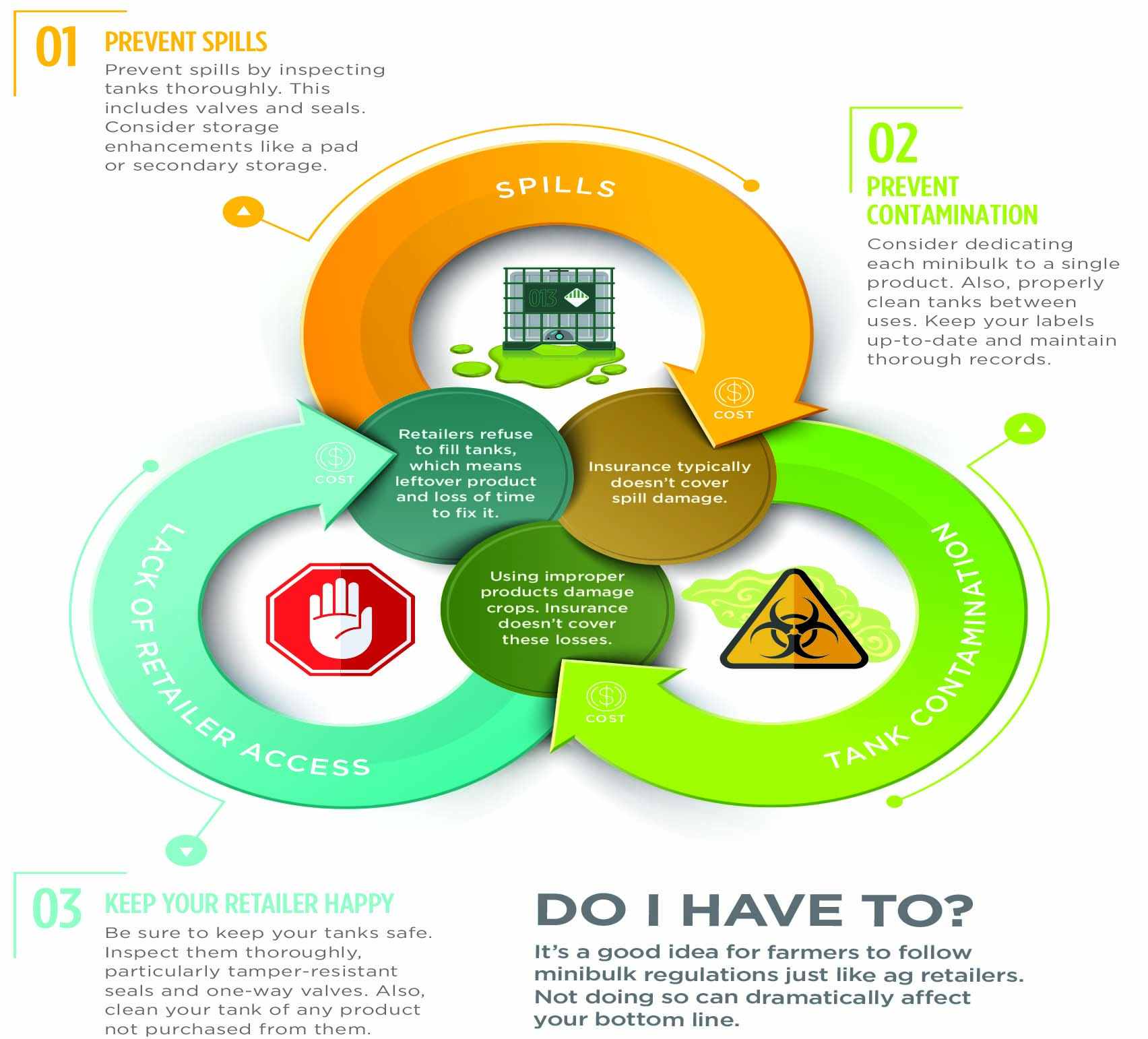

However, just because you don’t have to do something doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it! Consider the following problems that can be caused by ignoring industry requirements, common sense, and a few best-management practices.

Spills

If you never inspect your own minibulks, you almost guarantee a tank failure in the future. In addition, insurance policies do not normally cover spills along highways or ditches unless you added special coverage. The potential economic losses (not to mention environmental impact) from a pesticide spill could force a farm out of business.

Tank Contamination

Failing to dedicate minibulks to a single product or failing to properly clean minibulks can cause product contamination. Contamination usually results in sizeable crop damage and injury, which your insurance may not cover.

Tampering With Minibulks Is Serious

A nonscientific survey found few problems with farmers breaking seals or tampering with minibulks owned by retailers. If farmers return any tank to their dealers with any indication that seals, tags, or one-way valves have been damaged, the ag dealers are required to thoroughly clean the tanks according to the manufacturer’s directions as spelled out in the repackaging

agreement.

If a farmer breaks the seals, then the farmer may have to purchase the minibulk, pay to have it cleaned, or not receive credit for product remaining in the minibulk.

Retailers Won’t Fill Your Minibulk

Because retailers are required to follow repackaging agreements, they will not fill minibulks that do not meet the standards set out in their contracts. Farmer-owned tanks that don’t have one-way valves, have no tamper-evident seals, or worse, still contain product, represent huge liability risks for retailers. Likewise, retailer-owned minibulks that are returned with broken seals and leftover product also represent, at the very least, a dilemma for retailers — do they take a chance by taking the product back? Or do they possibly lose customers by telling them they will not accept the return?

The simplest way to avoid all of these possible problems is to use only retailer-maintained tanks that are returned in good working order with seals intact.

The most serious of the issues is the retailer’s response to material left in a shuttle when an inspection shows that the seals have been broken. The farmer may be asked to take the product home, since the retailer cannot know for certain whether the product has been adulterated.

Conclusions

There is no doubt that agriculture has embraced minibulk use as a very cost-effective and efficient way of moving pesticides from retailers to farms. The convenience of bypassing many smaller containers and the lower price

of bulk products makes minibulk use an important part of agricultural production.

Farmers and retailers know the benefits of minibulks well, but they also need to know about the concerns of spills and tank contamination. Retailers and farmers agree that the added cost of secondary containment and following repackaging agreements is significant. However, they also agree that following the regulations helps prevent spills, lower the frequency of tank cross-contaminations, and improve environmental quality. When farmers and retailers work together as part of a “minibulk system,” they both can reap the benefits of lower product cost and liability and increased safety and profit.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dawn Minns for graphic design. Thanks also to the following individuals who provided valuable comments and suggestions that improved this publication.

Brandon Bowser, Harvest Land Co-op

Chuck Croy, CERES Solutions

Patricia Dunn, Office of Indiana State Chemist

Ronald Hellenthal, Emeritus Professor, Notre Dame University

Patrick Hickner, Co-Alliance

Jeff Jeffries, Winfield Solutions

Matthew Pearson, Office of Indiana State Chemist

Brad Peas, AgroChem

David Peters, Bayer Crop Science

Doug Whicker, Co-Alliance

DISCLAIMER

This publication is intended for educational purposes only. The authors’ views have not been approved by any government agency, business, or individual and cannot be construed as representing a perspective other than that of the authors. The publication is distributed with the understanding that the authors are not rendering legal or other professional advice to the reader, and that the information contained herein should not be regarded or relied upon as a substitute for professional consultation. The use of information contained herein constitutes an agreement to hold the authors, companies or reviewers harmless for liability, damage, or expense incurred as a result of reference to or reliance upon the information provided. Mention of a proprietary product or service does not constitute an endorsement by the authors or their employers. Descriptions of specific situations are included only as hypothetical case studies to assist readers, and they are not intended to represent any actual person, business entity, or situation.

Reference in this publication to any specific commercial product, process, or service, or the use of any trade, firm, or corporation name is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement, recommendation, or certification of any kind by Purdue University. Individuals using such products assume responsibility that the product is used in a way intended by the manufacturer and misuse is neither endorsed nor condoned by the authors nor the manufacturer.

Reference in this publication to any specific commercial product, process, or service, or the use of any trade, firm, or corporation name is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement, recommendation, or certification of any kind by Purdue Extension. Individuals using such products assume responsibility for their use in accordance with current directions of the manufacturer.

Find out more at

The Education Store edustore.purdue.edu

October 2020