A Gardener’s Guide To Avoiding Costly, Harmful, And Illegal Pesticide Purchases

Fred Whitford, Director, Purdue Pesticide Programs

John Orick, State Coordinator, Purdue Extension Master Gardener Program

John Obermeyer, IPM Specialist, Purdue University

Jason Deveau, Application Technology Specialist, The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture,

Food and Rural Affairs

Anne Overmyer, Purdue Extension Master Gardener

Joe Becovitz, Pesticide Program Specialist, Office of Indiana State Chemist

Garret Creason, Pesticide Program Specialist, Office of Indiana State Chemist

Kevin Leigh Smith, Continuing Lecturer and Communication Specialist, Purdue Agricultural Sciences Education and Communication

The Perfect Weed Killer — Easy, Cheap, and Great Results………………4

Real Stories, Real Problems, and Real Danger………………………………..8

1. Cheaper by the Gallon, That’s for Sure ……………………………………….8

2. Better Than the Best………………………………………………………………….9

3. A Hodge-podge Weed Killer………………………………………………………11

4. You Can’t Beat Free …………………………………………………………………12

5. Nothing in the United States Works as Well………………………………..12

6. It Looks Like the Real Deal Except for One ‘Minor’ Point …………… 13

How to Quickly Identify Products That Are ‘Too Good to be True’…… 14

Warning Sign 1: Product Is Sold in a Food or Drink Container………….14

Warning Sign 2: Product Label Is Not Attached……………………………….14

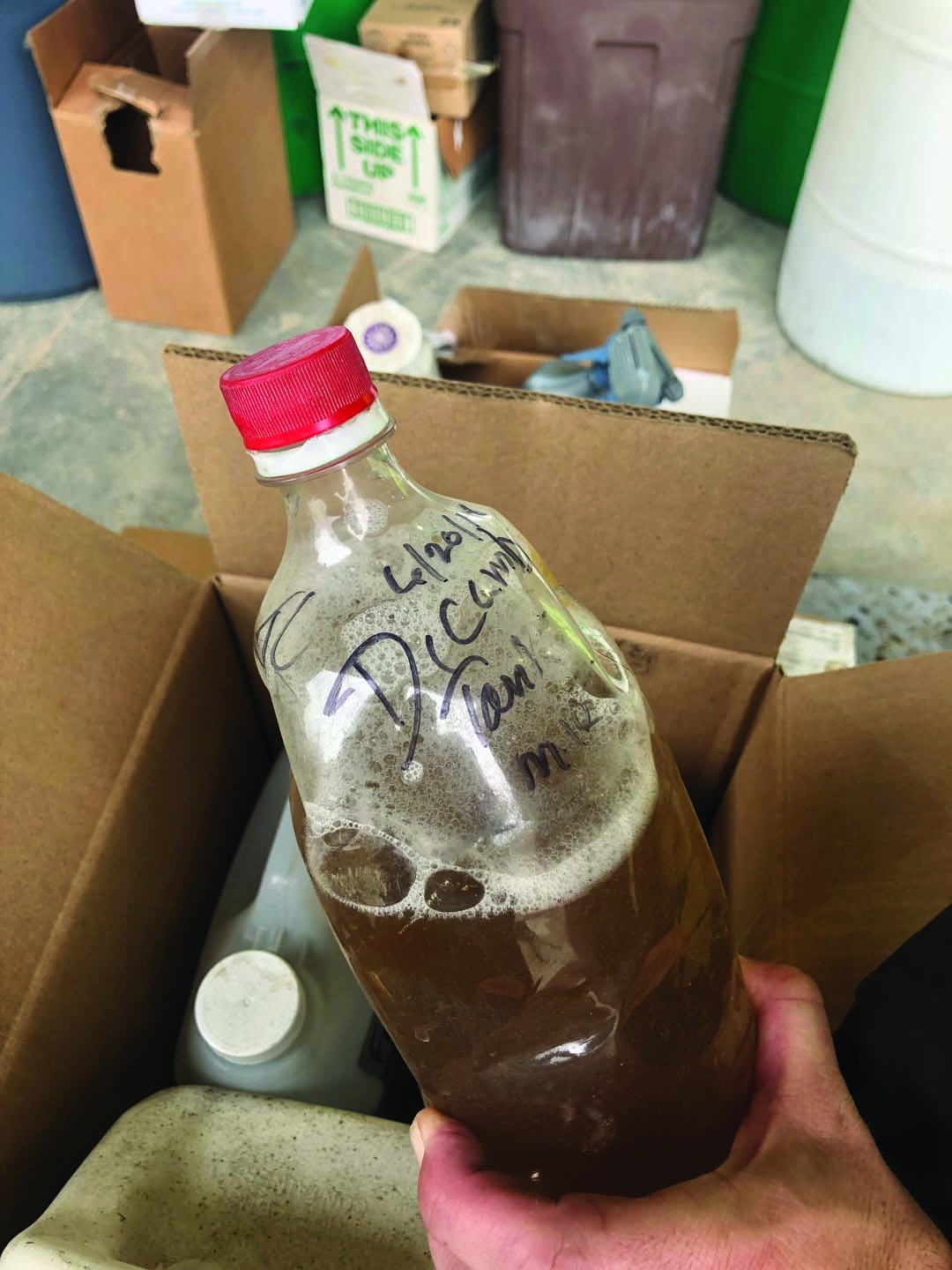

Warning Sign 3: Information Is Handwritten on the Container ………. 14

Warning Sign 4: Product Label Is in Another Language……………………14

Buyer Beware……………………………………………………………………………….16

Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………………. 18

Disclaimer……………………………………………………………………………………19

THE PERFECT WEED KILLER — EASY, CHEAP, AND GREAT RESULTS

Many homeowners struggle with maintaining their lawns, flower and vegetable gardens, landscapes, wooded areas, and water features. Insects and diseases are an occasional nuisance, but weeds are a constant problem. Despite homeowners’ best efforts, it seems like weeds proliferate and get worse every year. Some species seem downright impossible to control!

Many consumers believe the persuasive claims local retailers make, and then put their hopes in commercially available herbicides. Unfortunately, many products available to homeowners can be a huge disappointment. Sometimes that might be because homeowners disregard instructions and apply the products at rates far lower or higher than the instructions recommend. This is a very risky proposition that can possibly damage other plants, harm the people applying the herbicides, or result in poor weed control.

Some homeowners decide another option is to obtain the same herbicides that farmers or commercial landscape companies use. A quick internet search reveals that either homeowners cannot legally buy those herbicides, or the price is an exorbitant $125 for a quart-size container. For most people, this is not an economically viable solution.

Homeowners grudgingly accept the last resort: manual labor. This involves getting down on hands and knees to pluck weeds one-by-one or using hoes to remove them from lawns and landscapes. For small areas, this is not such a bad proposition. It might be even enjoyable and healthy. However, the problem with hand-weeding larger areas is that the job never ends. New weeds sprout and old weeds regrow constantly. There must be a better way.

Then, while visiting a garden show, homeowners may spot the answer to their weed control woes: a ready-to-use product with exciting claims like “Kills all weeds, instantly.” And what a bargain! But remember: when something seems too good to be true, it often is.

Wild onions spread rapidly in flower beds and lawns. They are very difficult to control, even with most herbicides.

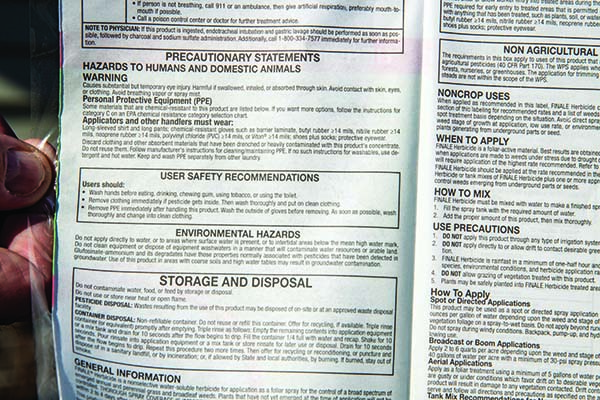

Wild onions spread rapidly in flower beds and lawns. They are very difficult to control, even with most herbicides.  Every legal pesticide product registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has a label that includes instructions on how to use the product to control pests and how to do so in a manner that protects the users, their families and neighbors, pets and livestock, fish and wildlife, and water.

Every legal pesticide product registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has a label that includes instructions on how to use the product to control pests and how to do so in a manner that protects the users, their families and neighbors, pets and livestock, fish and wildlife, and water. Many insects, weeds, and plant diseases look alike, but react differently to the array of legal pesticide products available and to other cultural options that also might control the pest. Correctly identify unwanted pests before purchasing any pesticide product. The product’s label will list the pests it controls. Applying “homemade” mixes is a real gamble and may worsen the situation.

REAL STORIES, REAL PROBLEMS, AND REAL DANGERS

In this section, we share six actual stories about “great deals” homeowners encountered in the search for the next best pesticide. As you read them, see if you can identify red flags that make you suspect product’s validity or safety. At the end of each story, we will point out the warning signs that should make you suspect these pesticides might be a useless (or worse, dangerous) purchase.

1

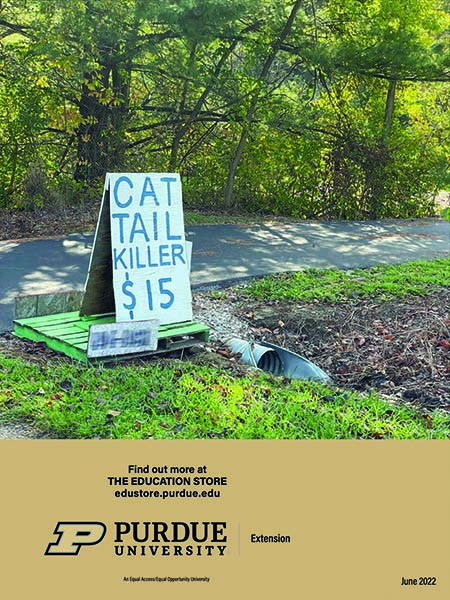

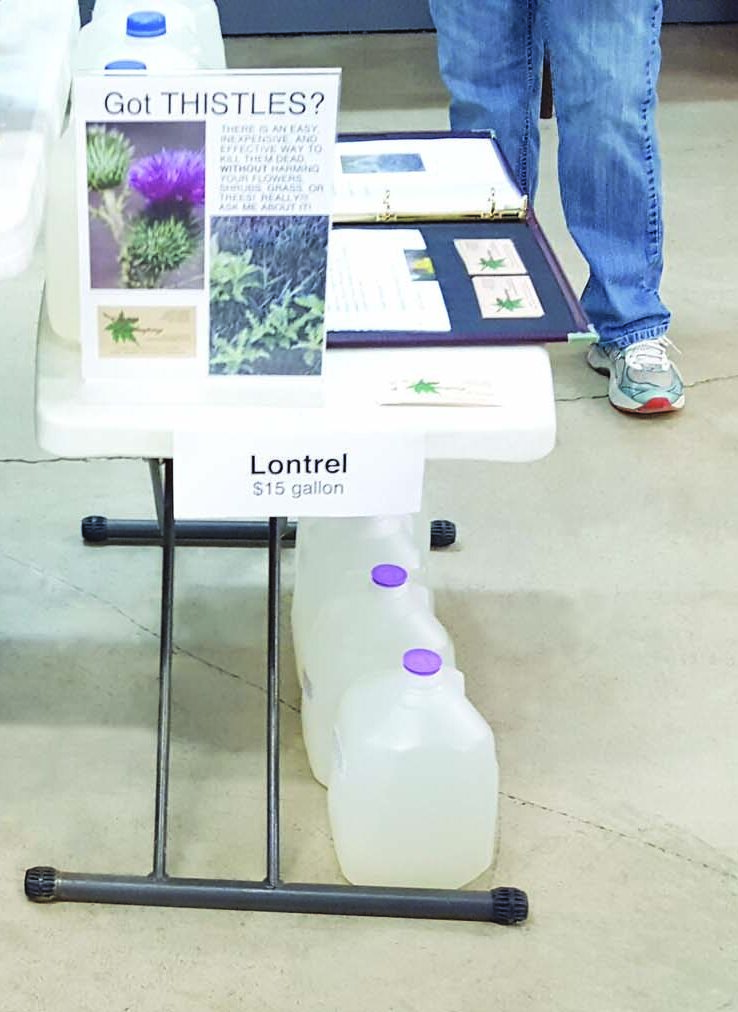

Cheaper by the Gallon, That’s for Sure

A consumer walked down an aisle at a garden show when a sign reading, “Got Thistles?” stopped him in his tracks. “Yes,” he thought to himself, so he read the information at the booth. The herbicide they were offering was Lontrel® and cost only $15 a gallon. He looked up Lontrel® on his smart phone and learned that it typically sells for an eye- popping $182 for a quart of concentrated product. For only $15, he bought a 1-gallon milk jug of premixed, ready-to-use Lontrel® to rid his yard of pesky thistles.

A few weeks after he applied the product to the thistles in his lawn, the tomatoes and peppers in his vegetable garden began to twist and curl severely and stopped growing. He couldn’t understand or explain what was ruining his prize tomatoes. With help of his local Purdue Extension educator, they identified the grass clippings as the cause.

The grass clippings were contaminated with Lontrel® which, at very low levels, can injure certain plants. In fact, the label for the commercial Lontrel® product approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), specifically warns users against using clippings for mulch or compost.

What were the warning signs in this example?

The first warning sign is that the herbicide was sold in a food (that is, milk) container. What legitimate pesticide manufacturer packages a pesticide in an easily recognizable food container? Doing so would be breaking federal and state regulations and exposing themselves to enormous liability. Nobody wants an accidental poisoning, especially children unable to read.

The second warning sign is that there was no label. The buyer could have downloaded one from the internet, but in this example he did not. If he had, the consumer would have read that Lontrel® cannot be used on residential turf. He also would have seen the warning against using the grass clippings for compost or on gardens.

A third warning sign is that there was no way to know how much active ingredient the mixture contained. How much Lontrel® was actually in that milk container? Could the homeowner trust the vendor to tell him? Did the seller even know?

What’s the story behind the story? The real winner was the salesperson who turned a $182 investment into thousands of dollars by diluting concentrated product and selling it in unlabeled and illegal containers. Unscrupulous vendors can make more money by using less product with more water. Can you trust someone who illegally sells pesticide to mix the product at the correct dilution? Knowing the rest of the story, should the consumer still buy the product?

2

Better Than the Best

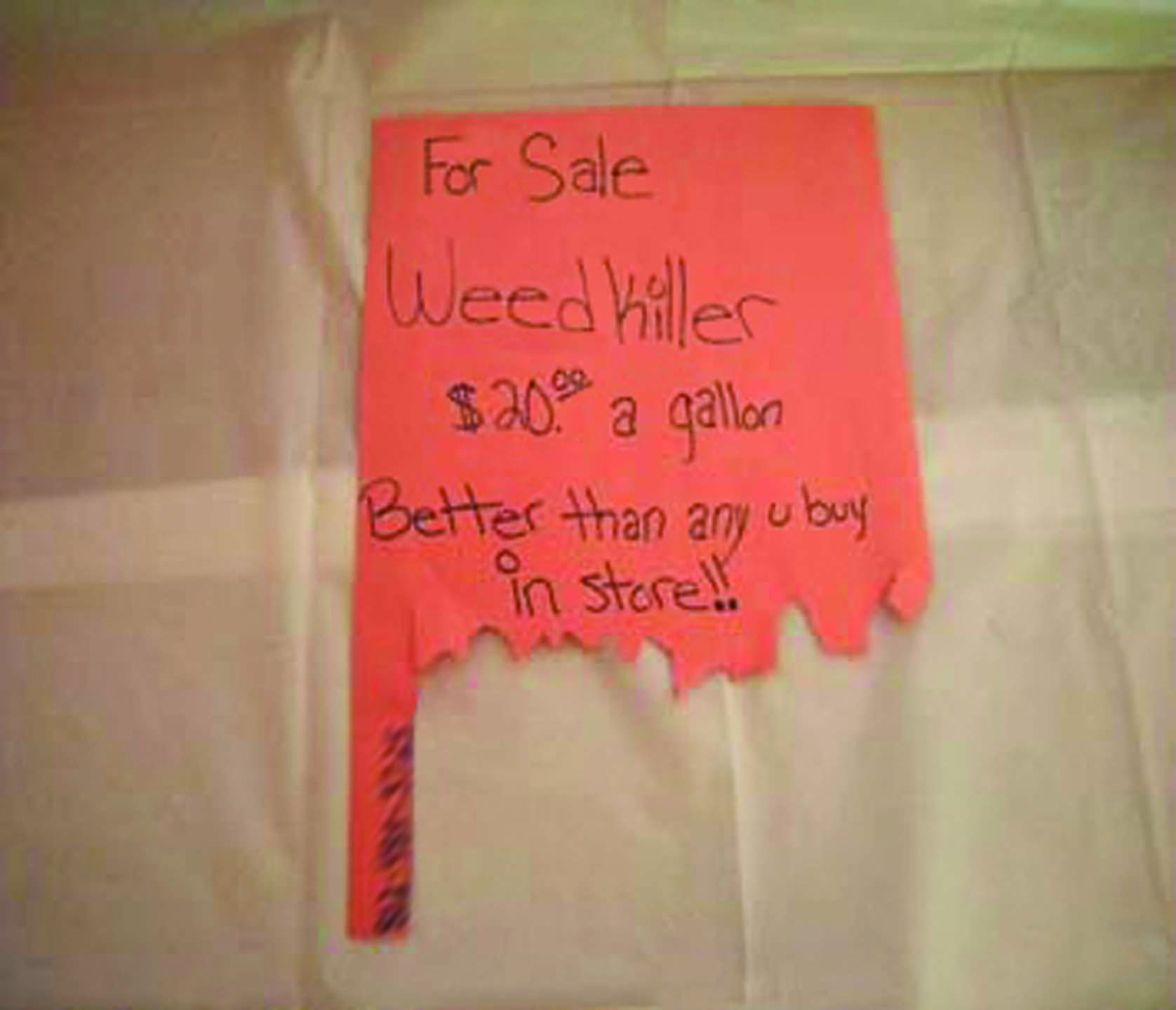

At a grocery store, an orange flyer on a bulletin board caught a homeowner’s attention: “For Sale: Weed Killer $20 A Gallon, Better Than Any U Buy In Store!!”

The homeowner called the number on the flyer to arrange a time to meet. When she asked for the product name, the seller was confused. At first, the seller called it “Pramoxone,” then later “Promoxicil.” The seller told the homeowner to mix 3 ounces of the concentrated product for each gallon of water she used in her sprayer.

The green-colored liquid looked and smelled pretty “wicked,” so the homeowner thought it must be a potent weed killer. The homeowner was hesitant to close the deal, but having driven many miles to meet the seller, she did not want to go home empty-handed. The homeowner shrugged, handed over $20, and put the gallon jug labelled IGA Spring Water in her car.

What were the warning signs in this example?

Again, the product was sold in a food container. Can children mistake this container for a sweet drink? Also, like the first example, there was no label that provided active ingredients or instructions.

The seller could not give a consistent name for the product. If he couldn’t recall what herbicide is in the container, what are the chances he also forgot the correct way to mix and use it?

What the seller and homeowner did not know is that the herbicide itself was not legal to sell to most homeowners.

What’s the story behind the story? It turns out that the seller obtained the product from a friend who had access to the herbicide at work. The active ingredient in the product was paraquat, which is highly toxic and carries a Danger/Poison warning on the label. In fact, this herbicide is so toxic that an undiluted teaspoonful can kill an adult and there is no antidote!

Paraquat is a restricted-use pesticide, which means that only applicators who pass state-administered test(s) can purchase and use products that contain this active ingredient. If there is a silver lining to this story, the green fluid the homeowner bought only had trace amounts of paraquat, which may only have made a person very sick. Should an untrained person buy and use this product?

Using illegal pesticide products could harm wildlife, pets, and plants around your home.

3

A Hodge-podge Weed Killer

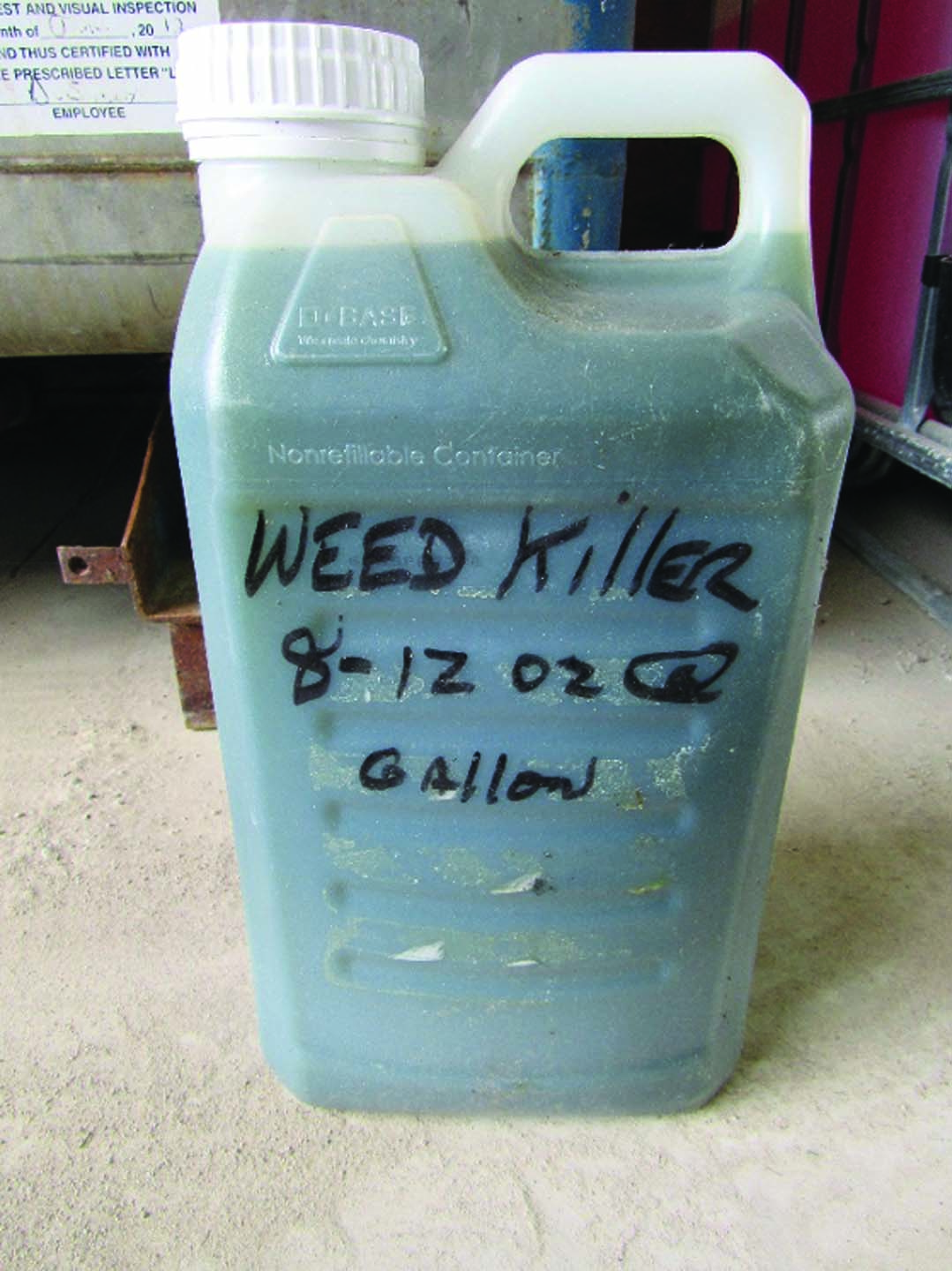

While scrolling through a social media marketplace, a gardener saw an advertisement for a weed killer. He texted the number for more information. The seller said he could furnish a 2.5-gallon container of this “herbicide” for $20, cash or check.

When the gardener asked the name of the product, the seller replied, “I just call it, ‘Weed Killer.’” When the gardener persisted and asked what was in Weed Killer, the seller replied, “It‘s a mixture of things. It‘s Roundup®, Gramoxone® [which is a trade name for paraquat], and all kinds of things. That‘s why it is a great weed killer!”

The gardener asked for a product label, but the seller claimed that the necessary information was written on the container, which appeared to be an herbicide container with the old label torn off and “Weed Killer” written on the side with marker. Just mix the concentrate as directed, and it is ready to use, the seller said.

What were the warning signs in this example?

The warning signs that this was not a legitimate product should seem familiar to our first two stories. Like we’ve already seen, this product came in an improper container. While it wasn’t sold in a repurposed food container this time, it appears that the seller repurposed two different sizes of pesticide containers to sell his Weed Killer. Federal and state law forbids reusing most pesticide containers, and a closer look at the container reveals the adhesive remnants of a label. This plastic jug was originally manufactured for another pesticide product. There’s no way of knowing what products that container might have held before. Even trace amounts of some products could cause real damage.

Once again, there was no label. Although the red, green, and black markers are quite artistic, they are a sorry and illegal substitute for an actual label. Labels contain a wealth of application, health, and safety information. What if a child is accidently poisoned by one of these products? Without a label it is impossible to know what is in the product, and this makes effective medical treatment much more difficult.

What’s the story behind the story? It turns out that the person selling “Weed Killer” was in charge of rinsing and recycling the pesticide containers for the company he worked for. The seller collected leftovers from the original pesticide containers and mixed them all together in 1- or 2.5-gallon containers for resale.

After analyzing the pictured containers, investigators discovered at least a dozen different pesticide products were present in each container. This hodge-podge of active ingredients may or may not kill weeds, but it will almost definitely damage desired nontarget trees and shrubs and contaminate the soil for years to come. Should gardeners buy this product?

4

You Can‘t Beat Free

A person told her friend about a local business that was offering the public free herbicide for use on weeds on sidewalks and driveways. This is exactly what the friend needed to eliminate the weed problem on her long gravel driveway. When the person contacted the company, the representative confirmed that the product was free, but the homeowner would need to bring a pickup truck to transport the 250 gallons of mix. The company representative did not have a product label for what he was giving away.

What were the warning signs in this example?

There are several warning signs this “free” herbicide may be more trouble than it is worth.

Think of the quantity. Can any homeowner really use 250 gallons of herbicide in their lifetime? Related to the quantity, where can a homeowner safely store that much pesticide? What if the unused product were to freeze over the winter, crack the container, and began leaking in the spring without being noticed?

And if storage is not an option, where is the label that tells the user how to safely dispose of remaining product?

What’s the story behind the story? In this story, a company was rinsing out herbicide from their crop sprayers with water, and then collecting the material in heavy-duty, plastic 250-gallon containers. There is no way to know how much actual herbicide remained in the resulting rinse water, except that it was obviously diluted. Clearly, there is no way to know if there is enough herbicide to control weeds as advertised. Should she haul away 250 gallons of this “free” product?

5

Nothing in the United States Works as Well

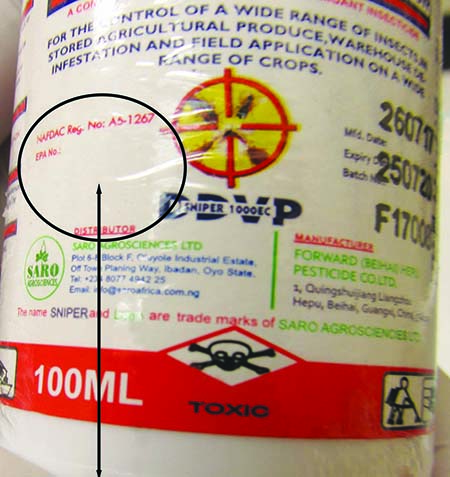

While shopping in a store, a customer asked the clerk whether the store stocks insecticides to control cockroaches. “Yes,” the clerk said and reached under the counter to grab a product called Miraculous Insecticide Chalk. The customer thought it was unusual that the product was not on the shelves and noticed there was no advertisement for this insecticide anywhere in the store. Was it a secret that the store carries Miraculous Insecticide Chalk? The customer asked why the directions are not in English and was told dismissively, “It’s just chalk. You don’t need any directions.”

What were the warning signs in this example?

At this point, the warning signs that this is not a legitimate product should be obvious. Specifically, the product was hidden away, and the directions had no English translation.

What’s the story behind the story? It so happens that the product in this example was smuggled into the United States and contains an active ingredient that is not approved for sale or use in the United States. In the United States, the EPA requires manufacturers to conduct specific tests concerning a pesticide’s health, safety, and longevity of residue in the environment.

Products that pass an intensive review are registered with the EPA and receive an EPA Registration Number, which is found on the front or back of the label and abbreviated as “EPA Reg. No.” Without the EPA Registration Number, manufacturers are not allowed to distribute or sell the product in the United States. Lacking this federal oversight and review may put the consumer in harm’s way. Should a gardener buy this product?

SPECIAL PESTICIDES EXEMPT FROM FEDERAL OVERSIGHT AND REGISTRATION

There are a few pesticide products that are deemed to be low risk and are exempt from federal registration because the active ingredients are commonly consumed food commodities, animal feed items, or edible fats and oils.

However, the labels for these exempt products still must list both inert and active ingredients, the company name, and their contact information. Furthermore, the label must not contain claims to control or mitigate organisms that pose a threat to human health. Many labels in this category state the product is a minimum risk or 25(b) pesticide, which helps identify them

6

It Looks Like the Real Deal Except for One ‘Minor’ Point

A consumer searched the web and found a product advertised as a cockroach, rat, and pest killer. The label said in large letters, “For Professional Use,” so the consumer thought it must be effective. Unlike the previous examples, this one really looks legitimate. It is in a manufacturer’s container. It has a professional looking label. The directions are written in English. However, upon closer inspection, there does seem to be a problem. Look at the label in the picture. Can you find an EPA Registration Number? There is no number.

What were the warning signs in this example?

Clearly, the lack of an EPA registration number should be a warning sign that something is not right. There is no way of knowing if the product is safe or even legal for use.

What’s the story behind the story? No pesticide product can be sold in the United States without an EPA number. Manufacturers spend hundreds of millions of dollars to perform the health and environmental research that the EPA requires to register a product. Unscrupulous companies often try to skirt the EPA registration processes that may be required rather than spend the money.

Certainly, this is cheaper for consumers, but importing and distributing illegal pesticides in the United States carries serious civil and criminal penalties. More important, this product very likely poses health and environmental problems, especially with indoor use. Should the homeowner buy this product?

DID YOU KNOW?

The label is the law. Every pesticide label contains this statement: “It is a violation of federal [and state] law to use a product in a manner inconsistent with its labeling.” By purchasing any pesticide product, you commit to using it in the manner described on the label.

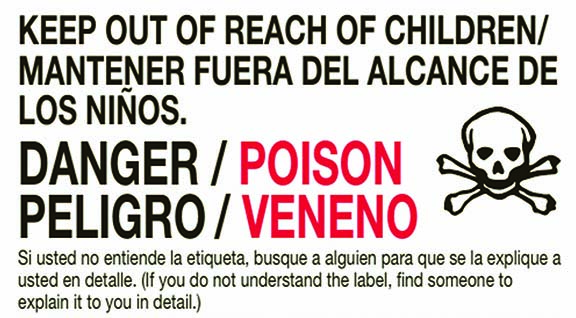

HOW TO QUICKLY IDENTIFY PRODUCTS THAT ARE “TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE”

The stories you just read lead us to outline four definite warning signs that indicate a possible “suspicious” product. If you encounter even one, you should remember the adage: “If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.”

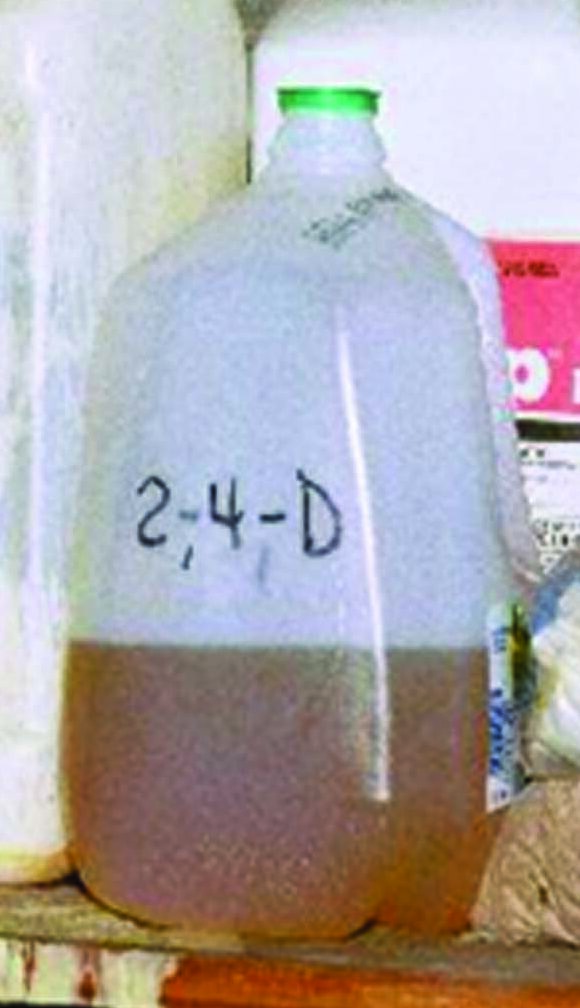

No reputable manufacturer will ever package its products in any container that is not intended for pesticides, especially in containers that are associated with food or drink. It would be confusing to consumers and is illegal.

Food containers may lead children, who recognize the containers, to mistakenly consume the pesticide. Furthermore, manufacturers also must test packaging materials to ensure the pesticide will not degrade or damage the container. By their nature, food containers are often made of lightweight and thin-walled materials that are not intended for the long-term storage of chemicals.

Manufacturers must attach EPA-approved labels to product containers that clearly communicate the contents of each container and provide instructions on how to mix, apply, and store the product safely. Labels also address emergency situations related to product use.

The examples of suspect products that we shared leave consumers without important information such as the actual contents of the containers, how to apply them, and which pests the products are supposed to control. More important, there is no information about how to use and dispose of the product safely.

Handwritten information confirms that the product is not in the manufacturer’s original container. If you spot a pesticide container with only handwritten information, that is a clear sign that someone has repackaged, and possibly tampered with, the product. You would never buy or take a medication that only has a handwritten note on the container. Likewise, you should never buy or use a pesticide with a handwritten note.

Consumers cannot use products safely and effectively if they are unable to read the instructions. This situation is no better than an unlabeled product. Obviously, if there is not EPA Registration Number on the container, the product is illegal in the United States.

It takes roughly 10 years and $450 million for manufacturers to register a new active ingredient and

be assigned an EPA Registration Number. If the EPA Registration Number on the front or back of the label is missing, then the product most likely is not allowed to be sold or used in the United States.

Thousands of pesticides are registered in the United States. All these pesticides have undergone a rigorous scientific review by the EPA. These products have registration numbers, are written in English, and contain detailed instructions for controlling pests with minimal risk to humans, animals and the environment.

Make sure that you also store pesticides properly. Whatever you do, do not store pesticide products in any type of food container.

BUYER BEWARE

The examples described in this publication might remind you of that time in American history when traveling “snake oil” salesmen came to town hawking magic elixirs. They were sold in colorful glass bottles filled with mysterious liquids and claimed near-miraculous cures to common ailments.

Most were, of course, hoaxes. In fact, some of the products actually worsened health conditions — some contained high levels of mercury and other dangerous substances. But sales pitches from clever charlatans always pique the interest of an unsuspecting audience — “A sucker,” they say, “is born every minute.”

Sadly, less has changed since then than we would like to think. In the case of pesticides, the mysterious solutions are likely to be found in plastic drink containers with handwritten labels that provide little or no instructions. Protect yourself and your investments by looking for the four warning signs and remember: “If it looks too good to be true, it probably is.”

WHAT SHOULD YOU DO IF YOU ENCOUNTER ILLEGAL AND DECEPTIVE PESTICIDE PRODUCTS?

If you ever come across someone selling a clearly illegal pesticide product, contact the Office of Indiana State Chemist at 765-494-1585.

You might ask why you should get involved? Simply put, you might be saving a life or property from these potentially dangerous chemicals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Dawn Minns for graphic design and Adduci Studios for illustrations. Thanks also to the following individuals who provided valuable comments and suggestions that improved this publication:

Jeff Burbrink, Purdue University

Anne Kline, Purdue University

DISCLAIMER

This publication is intended for educational purposes only. The authors’ views have not been approved by any government agency, business, or individual and cannot be construed as representing a perspective other than that of the authors. The publication is distributed with the understanding that the authors are not rendering legal or other professional advice to the reader, and that the information contained herein should not be regarded or relied upon as a substitute for professional consultation. The use of information contained herein constitutes an agreement to hold the authors, companies, or reviewers harmless for liability, damage, or expense incurred as a result of reference to or reliance upon the information provided. Mention of a proprietary product or service does not constitute an endorsement by the authors or their employers. Descriptions of specific situations are included only as hypothetical case studies to assist readers of this publication, and are not intended to represent any actual person, business entity, or situation. Reference in this publication to any specific commercial product, process, or service, or the use of any trade, firm, or corporation name is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement, recommendation, or certification of any kind by Purdue University. Individuals using such products assume responsibility that the product is used in a way intended by the manufacturer and misuse is neither endorsed nor condoned by the authors nor the manufacturer.