Unexpected Plants and Animals of Indiana: Peregrine Falcon

Indiana is home to a large variety of plant and animal life, supported by the range of Indiana habitats, from its prairies to verdant hardwood forests.

Discover some of the state’s more surprising species with Purdue Agriculture’s Unexpected Plants and Animals of Indiana series.

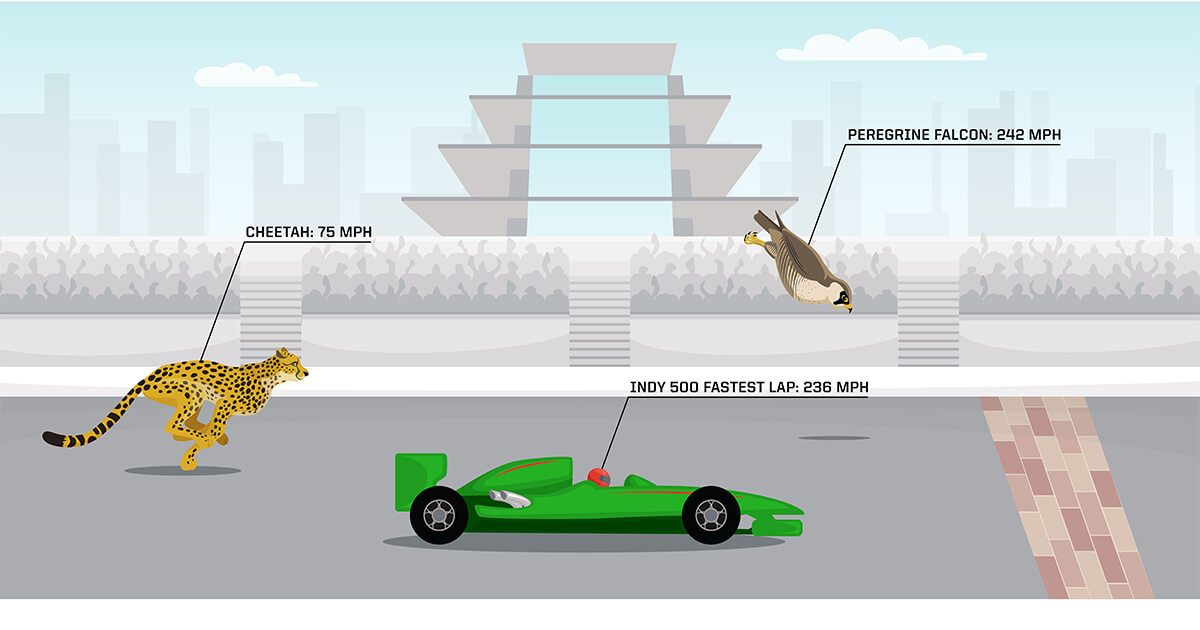

Indiana has a reputation for speed. The Indianapolis 500, known as “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing,” is recognized as one of the world’s most prestigious sporting events. In 1996, the fastest lap in Indianapolis 500 history was recorded at 236.103 mph. While incredibly fast, it still does not surpass the top speed of peregrine falcons: the world’s fastest animal and a native of Indiana.’

“Other birds of prey in our state, like hawks, have broad wings and tails that let them soar in circles for long distances before pouncing on prey. Falcons are more streamlined,” explained John “Barny” Dunning, professor of wildlife ecology. “Peregrines have a long, pointed tail and wings that funnel air around their body to build up amazing speed.”

During their dives, known as stoops, peregrine falcons have been recorded at 242 mph. Flying horizontally, peregrines travel in the range of 40-60 mph.

Graphic by Lauren Coghlan

Graphic by Lauren Coghlan The falcons’ speed enables them to use their bodies as weapons. During their stoops, peregrines close their talons in a fist and hit birds with a fatal blow to the head. They then circle back and catch their prey before it hits the ground.

“Peregrine falcons are one of the greatest successes of conservation in the United States,” added Dunning. “In the 1960’s and 1970’s there were large concerns about them going extinct.”

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), a pesticide that grew in popularity during World War II, made its way to peregrines through the food chain, causing them to lay eggs with frail shells that broke under the females’ weight.

The Environmental Protection Agency banned DDT in 1972 for use in the United States. Two years later, reintroduction programs began. Young falcons were released across the United States, particularly in the Midwest.

Before the reintroduction, most of Indiana’s peregrines lived on cliffs along the Ohio River and southern portions of the Wabash River. Most of the reintroduction sites were in cities.

“Peregrines feed on other birds, especially pigeons,” said Dunning. “And where are there a lot of pigeons? In cities.”

Tall structures like smoke stacks, bridges and towers provided ideal sites for the Department of Natural Resources to build nests. “The young birds grew up and adopted those nesting sites,” Dunning explained. “Now we have more breeding peregrine falcons than ever in our state.”

According to Dunning, the peregrines’ success is a great sign for Indiana. “There can’t be more predators than food in any natural habitat, so animals on top of the food chain are frequently the rarest. Therefore, they are often the most sensitive to the disturbances humans make. If you can have a healthy peregrine falcon population, that says a lot about the health of the city as a whole.”