Welcome to the Celery Bog Virtual Field Trip

As you read through the narrative, make sure to follow the imbedded links to additional background material and to numerous interactive 360° photos that open in separate browser tabs. You do not need to read the additional material in its entirety, but it is provided if you want to learn more.

Celery Bog Nature Area

The Celery Bog Nature Area is a 195 acre park managed by the West Lafayette Parks and Recreation Department. On this trip you will learn how Celery Bog formed, why it is called Celery Bog, what soils occur in the park, how the restored prairie is managed, and some of the environmental issues associated with the park.

Let's start by seeing where the park is located. Using the Google Maps app on your mobile device, or Google Maps in a browser, enter "Celery Bog Nature Area" in the search box. You'll see that the park is about a mile north of campus and that you can reach it by car, bus, bicycle or on foot.

The centerpiece of the nature area is the large wetland called Celery Bog. For a birds eye view, take a look at this panorama taken on Sept. 22, 2020 from a drone about 200 feet above ground level. The initial view is to the north. The large white roof you see next to the north end of the wetland is a Walmart. Look to the east and you'll see the Purdue Kampen Golf Course. Look to the south and zoom in and you can just see the Purdue water tower and the lights of Ross-Ade Stadium about 1.5 miles away. Turn to the west, and between the woods and the houses and apartments beyond, you can see the restored prairie that is part of the nature area.

Origin of the Wetland

The origin of what is now Celery Bog goes back about 15,000 years to the end of the Wisconsin Ice Age. How do you get a large depression in the landscape in the first place? There are at least two ways that seem likely here.

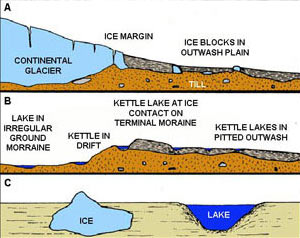

One explanation is that the depression is an ice block depression, also sometimes called a kettle hole, kettle lake or pit pond (the terms are synonymous), that formed as a buried block of ice melted as shown below.

The process is also described and illustrated more fully here. The problem with this hypothesis is that ice block depressions are usually associated with outwash deposits, while most of the soil parent materials around Celery Bog are glacial till deposited under the glacial ice, not outwash deposited in front of the melting glacier.

Another explanation is that the depression was scoured out by water. One possibility is that there was a large waterfall off the glacier as shown here, and that the waterfall scoured out a plunge pool at its base. Once the ice melted completely, only the depression was left behind. There are other possibilities that could result in depressions in a glacial landscape but they are more complicated. Whatever occurred, a shallow lake was left in the landscape at the end of the Wisconsin Ice Age.

After the glacial ice melted and the climate warmed, life reestablished itself. Initially, the area was a treeless tundra like the North Slope of Alaska today. As the climate continued to warm, the area became a boreal forest with coniferous tree species such as pine, spruce and larch. With further warming, the boreal forest was replaced by the hardwood forest we are familiar with today.

As the grasses, sedges, and other emergent plants that grew in the shallow water around the edge of the lake died, they fell to the bottom and were preserved by the anoxic (oxygen poor) environment at the bottom of the lake. Over thousands of years, the lake slowly filled in with organic material and became a freshwater marsh. Eventually, the lake filled in completely with organic material.

Bog or Marsh?

Wetlands are not all the same and there is a distinction between marshes, bogs, swamps, and fens. Bogs are acid, nutrient poor wetlands that receive most of their water from precipitation. They are dominated by sphagnum moss and are home to rare plants that can survive under acid, nutrient poor conditions. Marshes are nutrient-rich wetlands that receive most of their water from surface water. They are dominated by emergent soft-stemmed vegetation adapted to saturated soils. Swamps are any wetland dominated by woody plants. Fens are similar to marshes but receive most of their water from groundwater. By these definitions, Celery Bog is actually a marsh, not a bog. The name Celery Bog, however, was in use for some time before the marsh became part of the park, so Celery Bog it is.

Why is it called Celery Bog?

Sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s the marsh was drained by installing a tile drainage system that drained north into the McClure Ditch and then into Hadley Lake. This lowered the water level enough that the rich organic soils in the marsh could be farmed. The initial drainage and dewatering of the organic soil probably caused the soil surface to subside several feet.

In this article from the Lafayette Journal and Courier, Gordon Kingma describes how his family and at least three other families grew vegetables in the marsh, which they referred to as the slough, a word that means a wet, marshy area. The rich organic soils are great for vegetables, particularly root vegetables like carrots, onions, beets, and potatoes, because the low bulk density of the organic soil results in consistent, nicely formed roots and tubers. The families also grew celery. You'll need to read the article to learn how they watered the vegetables and how they grew the celery to produce white, crisp celery hearts for sale at Thanksgiving.

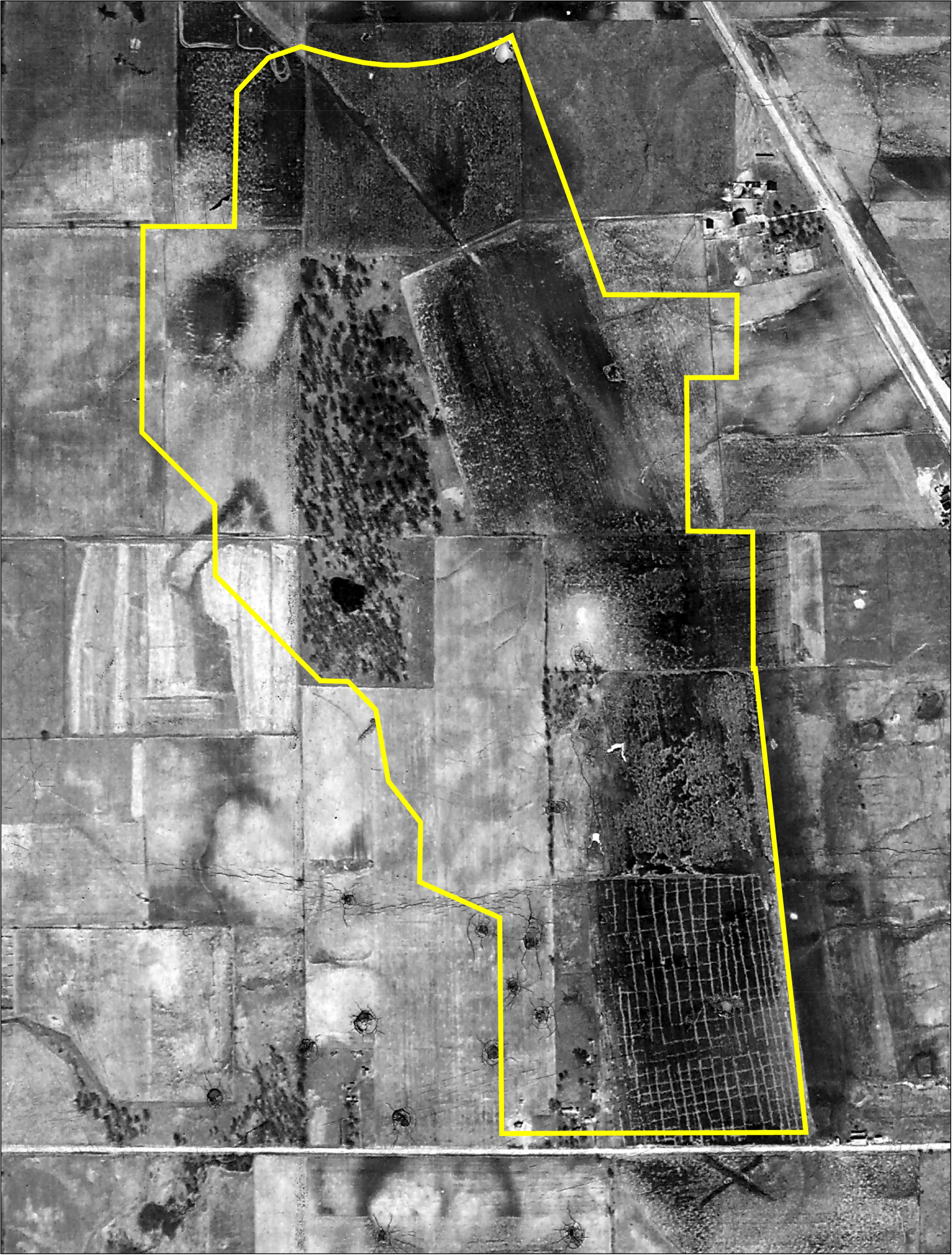

This aerial photograph from 1939 shows the marsh when it was being farmed. The yellow outline shows the approximate outline of the Celery Bog Nature Area today. The grid-like pattern at the south end of the marsh is probably the beds used to grow celery. (The round features that look like craters at the bottom of the photo are where someone damaged the photograph with a pointed object.)

Impacts of Drainage and Farming Organic Soils

Drainage and farming is hard on organic soils. When the water table is lowered, air enters the once waterlogged and reduced soil. With oxygen available, aerobic microorganisms can thrive. They use the organic matter as a food source, oxidizing the organic matter to carbon dioxide and water. The carbon dioxide is released to the air, contributing to the rise in CO2 in the atmosphere. The organic soil can even catch fire, burning away the stored carbon and releasing it as CO2 even more rapidly. This occurred at least once in part of Celery Bog. The net result of draining organic soils is a slow loss of the soil resource. The drainage tiles may even appear to come to the surface after they have been installed in organic soils, but that is not the case. The organic soil slowly oxidizes away and the soil surface subsides, exposing the drainage tiles. So the drain tiles don't come up to the soil surface, the soil surface moves down to the drain tiles. One additional hazard of farming organic soils is wind erosion. If the soil surface dries sufficiently, the light, fluffy organic soil material can simply blow away.

One strategy for reducing the loss of organic soils through oxidation is to lower the water table only during the growing season. At the end of the season, the drainage system is closed off so that the soil becomes saturated and remains so when it is not being used for growing crops. Whether this is practical, however, depends on the design of the drainage system.

By the 1960s, the tile drainage system in Celery Bog began to fail and water levels began to rise. The last field crops were grown on Celery Bog in the 1970s and the land began to revert back to a marsh. In 1990, the City of West Lafayette began to talk about purchasing the wetland and adjacent land for a city park and the first land was purchased in 1994. Celery Bog may look like a lake now, but the water is very shallow, only about 2 - 3 feet in many places. During the drought in 2012, the water level dropped enough that you could walk out onto the organic soil again. You can see what that looked like in this news article.

The Celery Bog Nature Area

The Celery Bog Nature Area opened to the public in October 1995, and the Lilly Nature Center was formally dedicated in 2000. The Nature Area continues to evolve. Trails and overlooks have been constructed on the upland on the west side of the park, while fence rows and other vestiges of its former use as farmland have been removed. Around 2010, a prairie restoration project was started on the west side of the park. This is the prairie that is visible in the panorama. If you drive into the Nature Area toward the Lilly Nature Center, the prairie is on either side of the road. Here is the Google Street View of the prairie taken sometime in the summer.

Fire as a Management Tool

One of the management techniques used for the restored prairie is prescribed fire. Prior to European settlement, prairies in the US burned regularly. Lightning strikes could ignite the prairie grasses naturally, but the Native Americans were probably responsible for most of the prairie fires as they managed the prairies for bison and other game. Half or more of the biomass in a prairie is below ground, and burning the above ground biomass has little impact on the below ground biomass.

Fire has many benefits in a prairie ecosystem. Fire controls trees, woody shrubs, and invasive species. Burning the accumulated litter stimulates new growth and allows new shoots to get enough light quickly. Burning quickly recycles nutrients back to the soil, and allows the soil to warm up faster in the spring. More information on the benefits of fire in grasslands is available in this article from the Nature Conservancy.

The restored prairie at the Celery Bog Nature Area is burned regularly too, as shown in this video.

The restored prairie at the entrance to the Celery Bog Nature Area was burned most recently on March 8, 2021.

Fire is used as a management practice in the forested areas of the park as well. In November 2020, part of the wooded area just to the north of the Lilly Nature Center was burned to clear out underbrush and unwanted maple trees so that the woods can be replanted to oaks and hickories.

Soils of the Celery Bog Nature Area

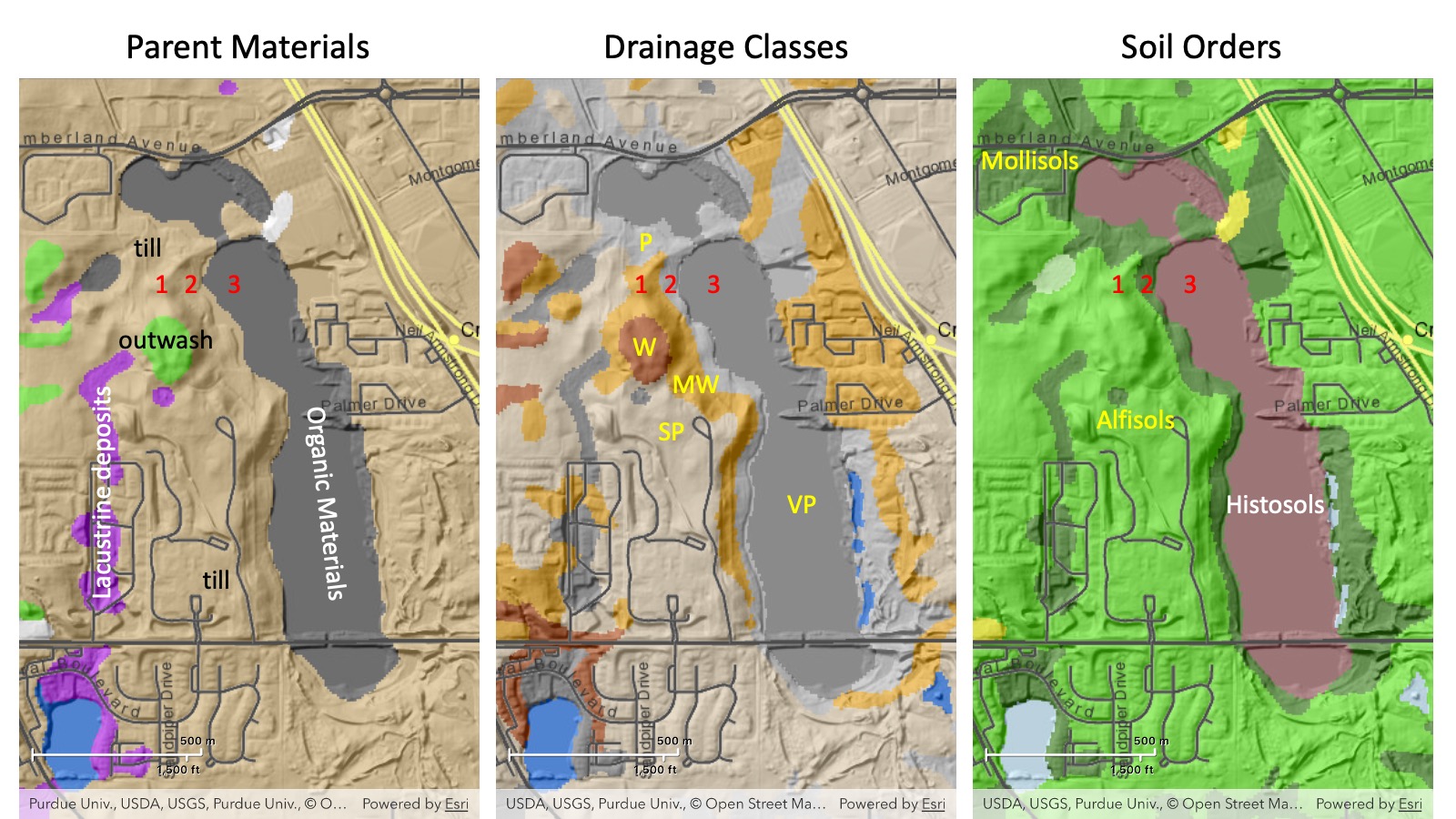

There is a lot of soil variably in the Celery Bog Nature Area as shown by the three maps below taken from the Soil Explorer app.

There are 5 different parent materials, four of them, loamy till, outwash, lacustrine deposits, and organic materials are labeled. The fifth one, loess, occurs on top of the soils on the uplands and can be up to ~50 cm thick if the soil is not eroded. There are 5 drainage classes, well (W), moderately well (MW), somewhat poorly (SP), poorly (P), and very poorly (VP) drained. Finally, the soils occur in 3 different soil orders, Alfisols, Mollisols, and Histosols. There are 7 different soil map units containing 9 different soil series. This is far more complexity than we are able to discuss here, so we will focus on only 3 soils, the three that occur at the locations labeled 1, 2, and 3 in red on the figure above. Note that these three soils form a toposequence, a sequence of soils that vary in a predictable, repeating pattern along a hillslope.

Starting at the top of the hillslope, Soil 1 is a Miami silt loam. Miami soils are moderately well drained Alfisols formed in loess over loamy glacial till. They formed under forest vegetation. The Miami soil, by the way, is the Indiana state soil.

Soil 2 is a Treaty silt loam. Treaty soils are poorly drained Mollisols formed in loess over loamy glacial till. They are the dark colored mineral soils that occur around the edge of the wetland and they formed under the grasses and sedges that grow there.

Soil 3 is the Houghton muck. Houghton soils are very poorly drained Histosols that formed in herbaceous organic materials more than 130 cm thick. The black herbaceous organic materials accumulated in a shallow lake as described above. In fact the organic materials are 15 - 20 feet thick in some parts of the marsh.

Environmental Aspects

If you did not have the satellite imagery turned on when you looked for the Celery Bog Nature Area on Google Maps, go back to Google Maps again and look at the aerial imagery. Celery Bog Nature Area is almost completely surrounded by urban areas. A large Walmart occurs at the north end of the marsh. The Kampen Golf Course occurs on the east and south end, and houses and apartments occur all around. Only to the west does some farmland remain, and that, too, is likely to be built up in the not too distant future. Celery bog receives runoff from all of the surrounding urbanized areas, so pesticides (herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides) and excess fertilizer nutrients can all run into the marsh if they are over applied or applied incorrectly. This is an obvious concern for the water quality and the aquatic life of the marsh. The golf course, the Walmart, and some of the housing developments have constructed artificial wetlands that are designed to filter out pollutants before they reach the marsh. Nevertheless, some nutrients still enter the marsh, contributing to the duckweed and algae floating on the water and visible in the panorama.

Celery Bog is also a groundwater recharge point for the Lafayette (Teays) Bedrock Valley aquifer, the aquifer that is the water source for Lafayette, West Lafayette, and Purdue University, another reason to try to keep the water in Celery Bog as clean as possible.