Assessing food awareness among food handlers and consumers in the Dominican Republic: A behavior theory approach

Why this research is being done

Foodborne diseases are global concerns, but low and medium-income countries are believed to be disproportionately affected. Foodborne diseases (e.g., salmonellosis, campylobacterosis, etc.), by definition, require direct contact with the etiological agent via food. As such, foodborne diseases can be prevented with behaviors that prevent an individual from ingesting contaminated foods. Such behaviors may be small, such as an individual avoiding known “high-risk” foods. These behaviors may also be systematic, such as a food processor implementing a food safety management system in a food production facility to minimize the risk of contamination of their product during processing (e.g., HACCP, GMPs, etc.).

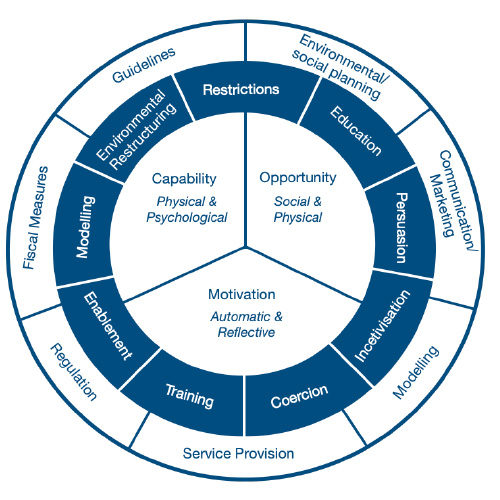

In either case, however, there must be change in behavior. Behavior change theories, in general, attempt to explain contexts, conditions, attitudes or perceptions that may drive a behavior. Thus, it makes sense to examine food safety behaviors using behavior change theory as a general theoretical framework. The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW; Figure 1), is a conceptual behavior change framework that allows implementers (e.g., public health professionals) to examine the conditions or sources (e.g., motivation) influencing a behavior (e.g., smoking cessation) and to use that understanding to build programs that better facilitate adoption of the behavior.

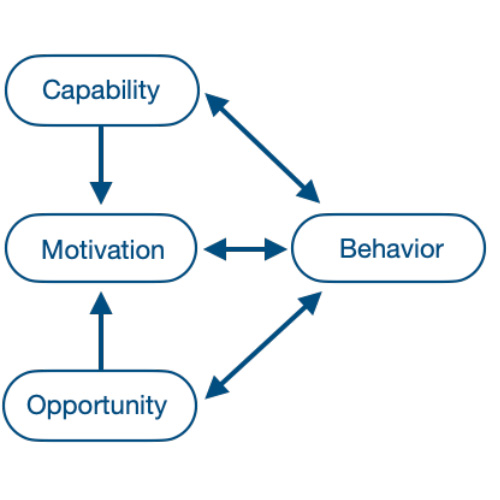

At the center of the BCW is the COM-B model of behavior change (Figure 2). The COM-B model is a distillation of dozens of behavior change theories into an actionable model. Briefly, the COM-B model posits that the combination of an individual’s capability, opportunity, and motivation to perform a behavior determines whether or not the individual will do the behavior. An individual’s capability refers to their psychological and physical capability to perform a behavior. Opportunity refers to “all the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behavior possible or prompt it”. Motivation encompasses myriad mental processes that may drive or direct a behavior (Michie et al., 2011).

Deficiencies in capability, opportunity, and/or motivation (or an individual’s perceptions thereof) decrease the likelihood of behavior adoption. Each condition, however, can be enhanced or improved through interventions, or behavior change techniques. The choice of which types of interventions to pursue is highly context dependent. Certain behaviors may be encouraged by education campaigns. For example, if an individual’s opportunity and motivation to perform a behavior are both high, but they are unsure as to how to perform the behavior (i.e., capability deficiency), the behavior could be enabled by a simple education or training program focused on development of relevant skills. In other cases, coercive interventions may be more effective or necessary (e.g., mandating specific training of individuals producing certain products). Both types of interventions are commonly used in efforts to improve food safety outcomes.

On the outside of the BCW are policies. Where interventions are designed to enhance a source of behavior (capability, opportunity, or motivation), policies describe approaches to best deliver those interventions. In the example of enhancing capability to do a behavior (when opportunity and motivation are high) through education programs that instill skills needed to do the behavior, such education programs could be delivered through communication/marketing, whereas the coercive interventions mentioned might require regulation or legislation.

Here, we asked consumers or food handlers in the Dominican Republic a series of questions assessing their awareness of food safety. We then used the BCW as framework to analyze how participants’ responses may serve as indications as to their likelihood of adopting of food safety behaviors. More specifically, we hoped to understand: 1) DR consumers’ and food handlers’ capability, opportunity, and motivation to adopt food safety behaviors; and 2) interventions and corresponding policies that could maximize these conditions thereby facilitating adoption of food safety practices.

Figure 1: The Behaviour Change Wheel.

The inner hub contains sources of behavior: capability (physical and psychological), opportunity (social and physical), and motivation (automatic and reflective). The inner blue wheel contains behavior change interventions. Interventions are the approaches that could be used to enhance or maximize a source of behavior. The outer white wheel contains policies. Policies are the means by which an intervention is delivered. Adapted from Michie et al., 2011 and Michie et al., 2014.

Figure 2. The COM-B Model of Behavior Change.

Sources of behavior (capability, opportunity, and motivation) influence one another and individually or collectively drive behavior.

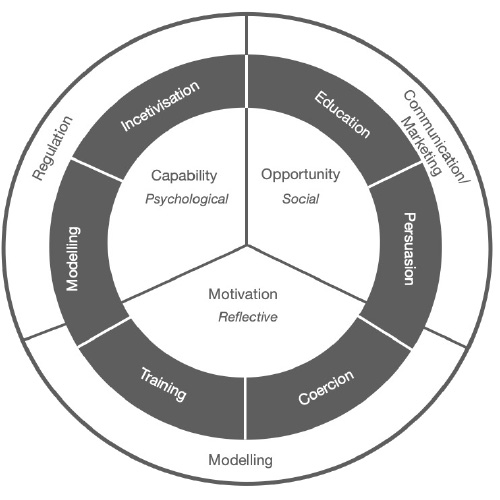

Figure 3. An intervention strategy to facilitate adoption of food safety behaviors in DR consumers and food handlers by enhancing their: 1) psychological capability; 2) social opportunity; and 3) reflective motivation to adopt food safety behaviors. These sources of behaviors could be enhanced via a combination of intervention functions including: 1) training; 2) education; 3) coercion; 4) persuasion; 4) incentivization, and 6) modelling. The six intervention functions could be delivered through: 1) regulation; 2) communication/marketing; 3) and modelling.

Results

This study was designed to allow data-informed development of food safety Extension and education programs in the DR. Based on analysis of more than 500 responses to questions related to food safety awareness, we identified numerous barriers to the greater adoption of food safety practices by both consumers and food handlers in the DR. Using the behavior theory approach, however, we propose a multi-pronged intervention strategy that could lower those barriers and increase adoption of food safety behaviors among DR consumers and food handlers. As a framework, this strategy could use a communication/marketing approach that increases reflective motivation, psychological capability, and social opportunity to adopt food safety behaviors. This intervention strategy is described schematically with a revised BCW in figure 3. More specifically, this strategy should:

- Maximize consumers’ and food handlers’ understanding that: a) contaminated foods sickens and/or kill millions each year (education); b) children and the elderly are most susceptible to foodborne diseases (persuasion); and c) there are easy ways to protect their health and the health of their families and communities (education).

- Incentivize adoption of food safety behaviors among food handlers (incentivization);

- Expand inspection of food markets to include food safety requirements (coercion);

- Provide consumers and food handlers with knowledge related to how food safety behaviors are performed (education, training); and

- Amplify relatable models of other individuals or groups currently implementing food safety practices and benefiting in some manner from those practices (e.g., improve health outcomes, increased revenue/markets, etc.; modelling).

Together, these efforts can create the environment that enables DR consumers and food handlers to improve food safety outcomes throughout the country.

Conclusions

These results have been shared widely with Dominican Republic government agencies (e.g., Ministry of Public Health, Department of Food Safety). We will begin working with these agencies to use these data to create policies and/or regulations that decrease the risk of foodborne disease associated with food consumed in the DR.

Contact information

Paul Ebner pebner@purdue.edu | 765-494-4820 | Purdue ANSC Directory