Study: Hormone keys plant growth or stress tolerance, but not both

Plants that grow well tend to be sensitive to heat and drought, and plants that can handle those stresses often have stunted growth. A Purdue University plant scientist has found the switch that creates that antagonism, opening opportunities to develop plants that exhibit both characteristics.

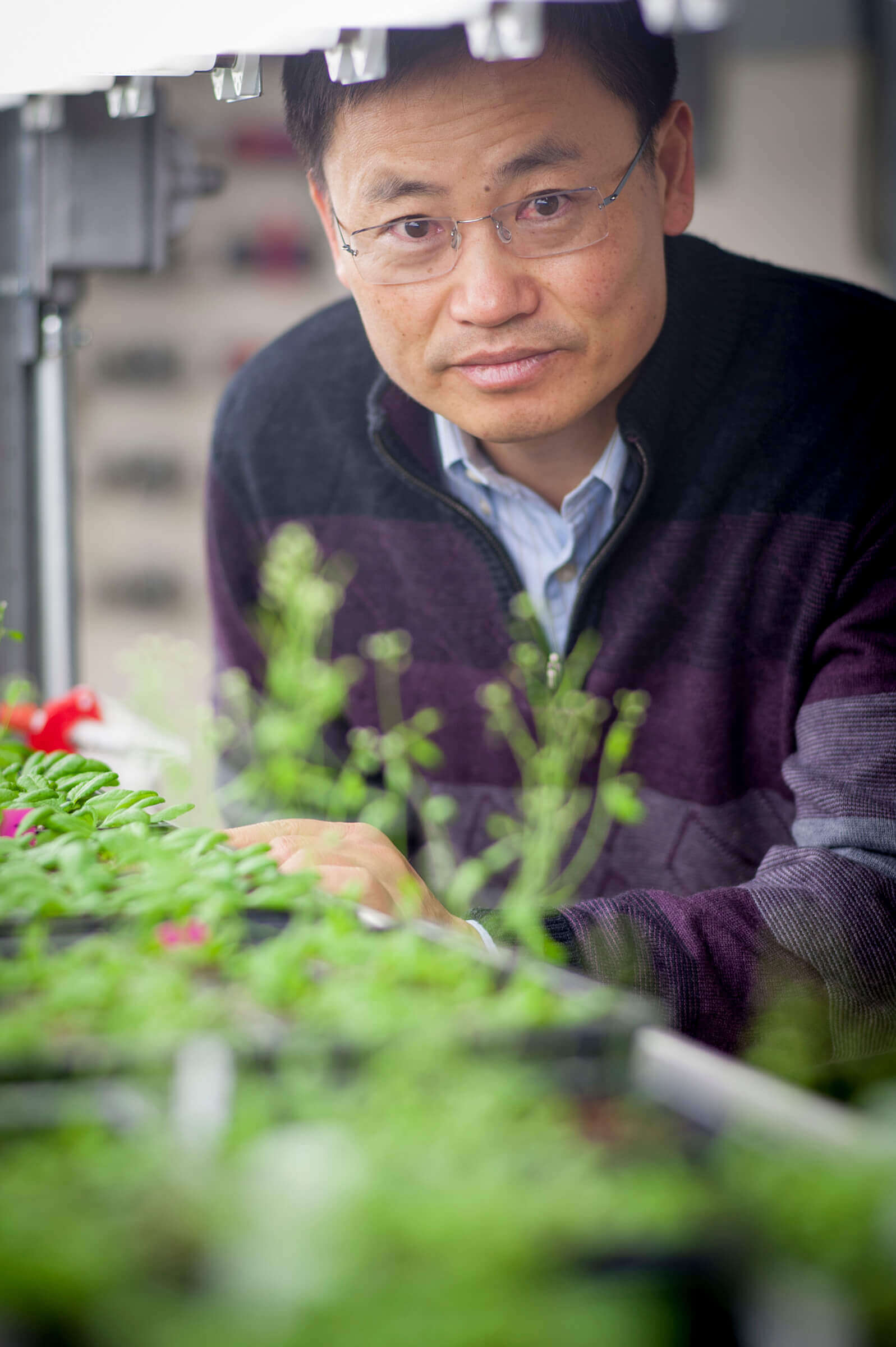

“Normally these two are antagonistic, but in nature, some plants tolerate stress and grow well. The questions is why some plants can have both, but most plants cannot,” said Jian-Kang Zhu, distinguished professor of plant biology in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture. “Once you know how the stress response and growth pathways are connected, hopefully we will be able to decouple them.”

Working with model plant Arabidopsis, Zhu found that abscisic acid (ABA), a plant hormone, is activated in plants that can tolerate stresses such as salt and drought. But ABA sets off a chain reaction that stymies plant growth.

Zhu found that in stressed plants, the ABA pathway is activated and leads to phosphorylation of the Target of Rapamycin (TOR) kinase. This essentially turns off the TOR kinase, which is essential for plant growth.

The opposite happens in unstressed plants. TOR disrupts ABA perception, shutting down the plant’s stress responses. Those plants tend to exhibit strong growth.

“This is the key to the antagonism between stress and growth,” Zhu said.

The findings, published in the journal Molecular Cell, could help scientists and breeders who want to develop plants that can handle environmental stresses and still grow well.

The Chinese Academy of Sciences and the U.S. National Institutes of Health supported the research.