From lab to table: Purdue Food Science research predicts texture with machine learning

The creaminess of custard. The fizz of foam. The slurpability of soup.

Texture is just as essential to our eating experience as flavor and smell. But it’s notoriously difficult to predict the all-important “mouthfeel” of food during the development process.

A new paper published in Food Research International changes that. Developed by a student research group in the Transport Phenomena Laboratory in the Department of Food Science at Purdue University’s College of Agriculture, the study introduces an artificial intelligence model to accurately predict texture perception.

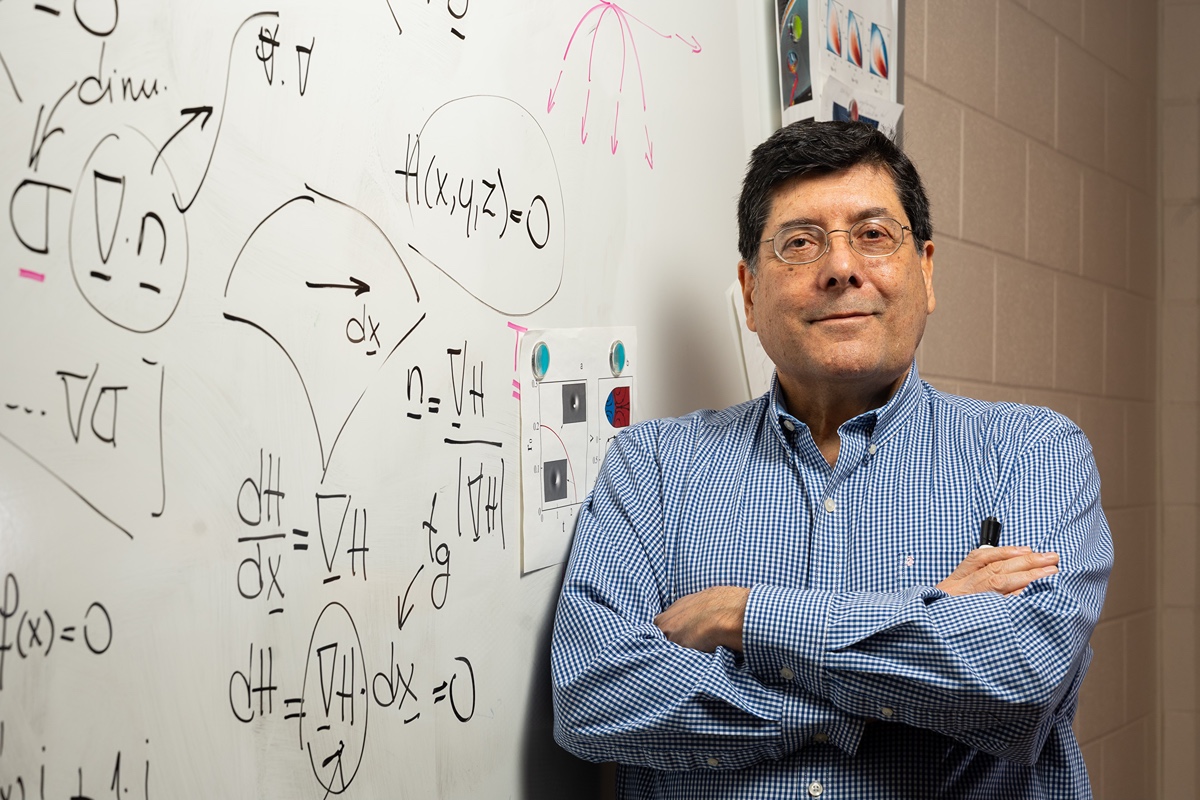

“We’ve developed an AI tool that predicts how food feels in the mouth based on physical properties we can measure in the lab,” explained Carlos Corvalan, associate professor of food science and the project’s supervisor. “It allows us to pave the way for smarter food design.”

Food development typically happens in cycles: recipes are created, cooked, tasted and then adjusted incrementally to improve flavor and texture. It’s a laborious, costly and time-consuming process.

It’s also subjective. Tasting panels consist of human testers with unique palates and preferences. Despite the existence of precision instruments to measure the chemistry and physics of food, determining the way it will feel when eaten can’t easily be summed up.

Corvalan is an engineer at heart: “I want equations to predict things,” he said. “But predicting sensory feelings – there is no equation for that. The link between quantitative properties and subjective feeling is very complex.”

That is especially true for non-Newtonian liquids like ketchup or yogurt, which flow differently under stress. To make things even more challenging, different formulations and ingredients can result in the same perceived texture, even if their physical properties differ.

This is the problem Corvalan and his students set out to solve in his new graduate-level course, Scientific Machine Learning. The project-based class combines scientific and engineering knowledge with breakthrough AI tools.

Paul Kraessig, the paper’s lead author and investigator, was an undergraduate majoring in computer science and honors mathematics when he conducted the research. Under Corvalan’s guidance, he developed a sensory-based autoencoder – a type of neural network designed to learn how humans perceive texture.

Unlike most machine learning models, which require massive data sets, this system can work with very small sample sizes. The model was trained using data from just a few bouillon samples, originally published in a Nature Communications paper examining the perceived thickness of liquids.

To ensure reliability from a limited dataset, the autoencoder uses a statistical method called cross-validation. This divides the data into multiple subsets to rigorously test the model’s ability to generalize without overfitting.

“Machine learning can sometimes be a bit of a black box,” noted Corvalan. “This shows you can do real-world predictions with very, very few data points and careful validation.”

Kraessig’s co-authors, Shyamvanshikumar Singh and Jiakai Lu, are also Corvalan’s former students. Lu, who received his master’s degree and PhD from Purdue, is now an assistant professor in the Department of Food Science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

The collaboration between Purdue and UMass Amherst is part of a research hub called Scientific Machine Learning for Food Manufacturing. The initiative is focused on optimizing food design and production.

Using the autoencoder, food developers and scientists can work much more efficiently. The model predicts how texture will be perceived without having to undergo continuous rounds of development and testing.

“The main objective is to design more appealing foods,” Corvalan said. “With this technology, we can determine how to improve texture while managing the cost and quality of ingredients.”

The hub has received funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, supporting further research into the texture and perception of food. One project includes developing plant-based (or “surrogate”) fish that mimics the texture of real seafood.

Interest in the hub is growing, with other universities and industry partners looking to join. Corvalan and Lu expect the research network to grow as AI becomes a more integral part of the food innovation.

The potential impact of this work extends beyond culinary curiosity. Texture isn’t always just a matter of preference – it can be a nutritional necessity.

For people with difficulty swallowing, such as the elderly or stroke patients, the texture of food is critical. Too thin, and it can cause aspiration. Too thick, and it can be difficult to consume safely.

“With this tool, we can reverse-engineer foods that are tailored to people with particular needs,” explained Corvalan. “It’s very, very important to get the texture right in those cases.”

By publishing their findings as open research, Corvalan and his team invite food scientists and developers around the world to build on their work. This ensures its potential benefits, whether improving food safety or making products more appealing, are shared more widely and equitably.

The research emerging from Purdue’s Transport Phenomena Laboratory is a major leap forward in food science, opening the doors for smarter, faster, and more precise food design. As the use of machine learning and AI in food science continues to expand, it’s clear that the future of food won’t just taste better – it will feel better, too.