Purdue researchers discover new transportation route for plant volatile compounds

Flowers use volatile compounds called terpenes to communicate with and protect themselves from the outside world. The aromas produced welcome pollinators while warding off pests and disease.

Now, a Purdue University study shows that petunias use terpenes in a sort of internal communication and to improve the plant’s reproductive capability. Natalia Dudareva, a Purdue distinguished professor in the Department of Biochemistry and lead on the research, published the findings in a paper featured on the cover of the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

“In general, volatile compounds help in plant-to-plant communication and defense, but this is the first time we’ve seen that plants use these compounds for inter-organ communication and signaling,” Dudareva said. “It’s practically a new physiological process that we’ve never known before.”

Dudareva, along with co-authors Benoît Boachon, a former research associate in Dudareva’s lab, researchers in the labs of Purdue’s John Morgan and Sharon Kessler, and colleagues from the University of Salzburg in Austria, showed that before a petunia flower opens, the bud acts as a sort of fumigation chamber.

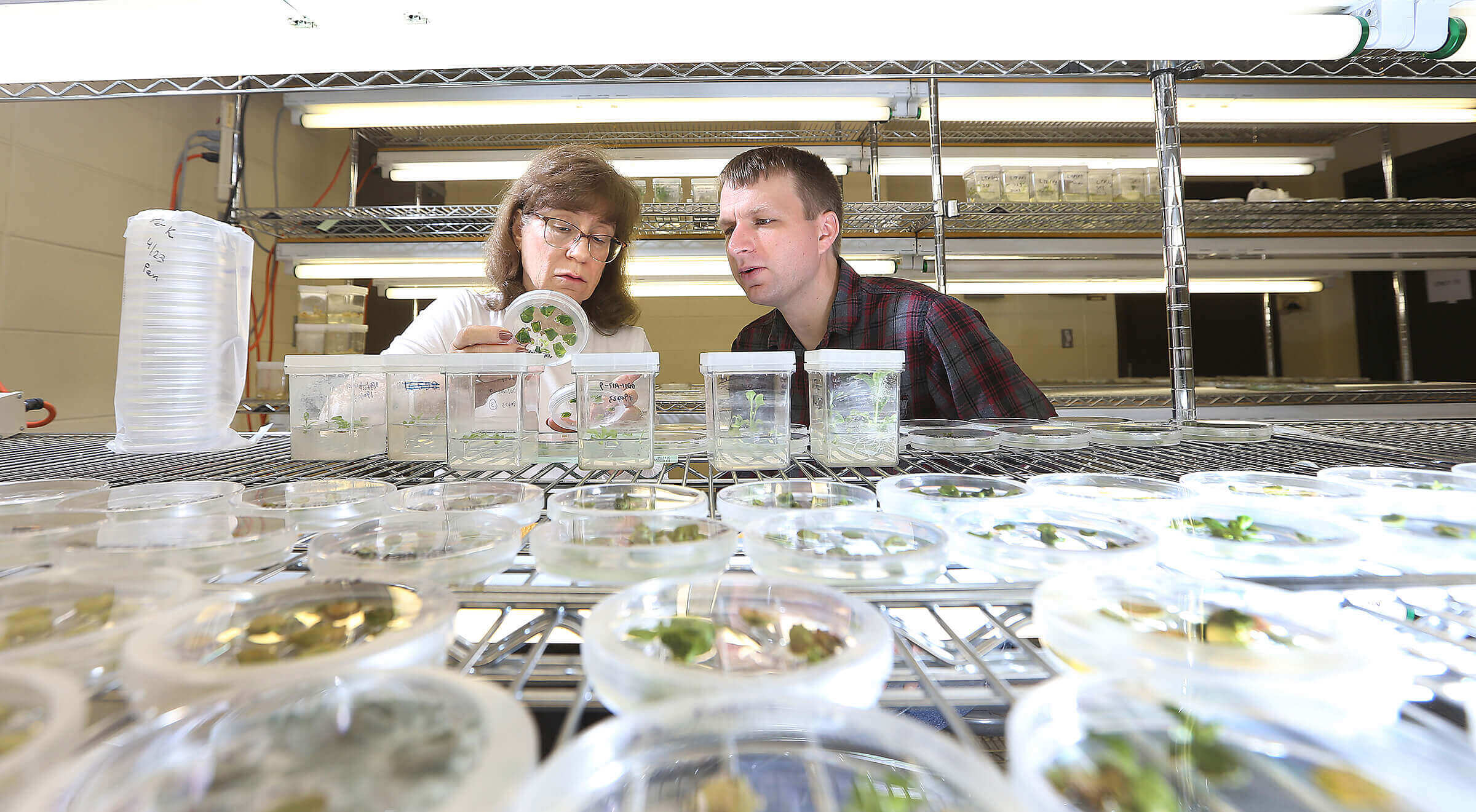

Purdue University’s Natalia Dudareva and Joseph Lynch, an associate research scientist in Dudareva’s lab, determined that petunias naturally fumigate themselves, transferring volatile compounds from flower tube to the stigma. The process is important for plant defense, health and reproduction. (Purdue Agricultural Communication photo/Tom Campbell)

Purdue University’s Natalia Dudareva and Joseph Lynch, an associate research scientist in Dudareva’s lab, determined that petunias naturally fumigate themselves, transferring volatile compounds from flower tube to the stigma. The process is important for plant defense, health and reproduction. (Purdue Agricultural Communication photo/Tom Campbell) “We were looking for the occurrence of terpenes in the reproductive organs of petunia flowers, and we noticed that these compounds were accumulating in the stigma. But the expression of the gene and the activity leading to the biosynthesis of these terpenes were not happening in the stigma. It was happening in the flower tube,” Boachon said.

Researchers performed three experiments to confirm their fumigation hypothesis – that terpenes present in the stigma were actually generated and emitted from the flower’s tube and then aerially transported and later absorbed by the stigma.

First, they grew the flower bud without the tube and noted that there was significantly less terpene accumulation in the stigma. Next, they added a label to the compounds in the flower tube. Later analysis showed that the labeled compounds were found in the stigma.

Finally, they silenced the gene that produces terpenes in the flower tube. The resulting flowers had less terpene accumulation in their stigmas. The terpene accumulation could be restored in stigmas with the gene silenced simply by placing them in tubes with the gene active.

Surprisingly, petunias lacking fumigation of terpenes from the flower tube also produced smaller stigmas and about 30 percent fewer seeds. That suggests that controlling terpene production in plants could increase seed production, something not considered before this work.

“Volatile compounds were assumed to be involved in defense and communication, but not in the development process,” Dudareva said. “Now we see they have functions similar to hormones. It could be possible to improve reproductive organs development and increase seed yield. This opens a new field for the study of a physiological process involving these compounds.”

The National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture supported this research.

A petunia bud that has not opened (top) will aerially transfer volatile compounds from the tube of the flower to the stigma before opening. The discovery, by Purdue University scientists, is the first organ-to-organ communication detected in flower. (Purdue Agricultural Communication photo/Tom Campbell)

A petunia bud that has not opened (top) will aerially transfer volatile compounds from the tube of the flower to the stigma before opening. The discovery, by Purdue University scientists, is the first organ-to-organ communication detected in flower. (Purdue Agricultural Communication photo/Tom Campbell)