Purdue program changes the drift of communication

A dozen years ago, Steve Smith could anticipate the calls coming in from farmers across the state. They’d report when and how much of their crops had been damaged as glyphosate being sprayed on nearby fields caught the wind and landed on their non-resistant tomatoes.

“We were having tremendous annual drift episodes, maybe eight to 10 per year, and it was getting worse all the time,” said Smith, senior director of agriculture for RedGold. “In the previous four or five years, we had experienced around $1.5 million in drift damage.”

RedGold, an Indiana-based tomato processing company, had few options back then. The company would try to determine where the herbicides had come from and contact the farmer who had sprayed them. In the best cases, the two sides worked through that farmer’s insurance company, and RedGold was compensated. Other times the sides might wrangle over the issue in court for months or years.

Tired of dealing with damage after the fact, Smith asked Purdue’s College of Agriculture for help.

“We needed to be proactive rather than reactive and filing lawsuits. That doesn’t help if we don’t have tomatoes,” Smith said.

He connected with Bernie Engel, then the head of the college’s Agricultural & Biological Engineering Department and now associate dean of agricultural research and graduate education. Engel realized that most of the drift problems could be avoided with better communication.

“The damage was occurring because of a lack of communication among growers about where sensitive crops were located,” Engel said. “A lot has changed and many people may not know their neighbors anymore. They may not have those conversations about what their neighbors are planting year to year.”

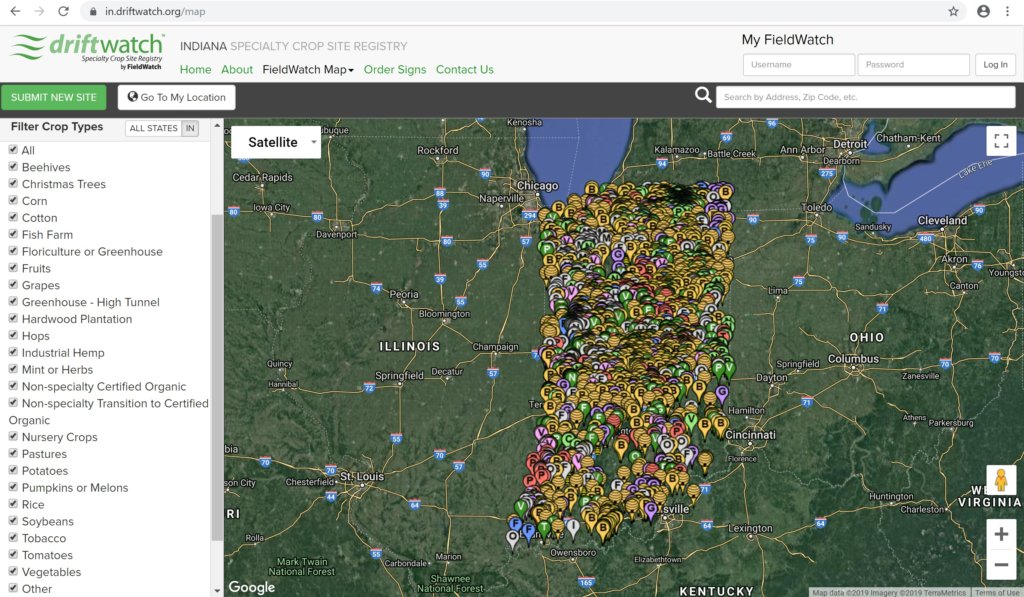

Engel’s solution was DriftWatch, an interactive tool that allowed farmers and the crop protection industry to identify and map sensitive or specialty crops grown each year. Nearby farmers and pesticide applicators can check the map before they spray herbicides and connect with specialty crop growers to develop strategies to reduce the likelihood of drift events. Engel said funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Office of the Indiana State Chemist, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency made the original program possible.

Within a few years, specialty crop growers saw drift incidents plummet. Smith said RedGold may see as many as two incidents per year these days, but in many years there are none at all.

“When we do have an event, it has been a lot smaller than what it was before,” Smith said. “And it’s usually not because a person didn’t know about our crops. They just made a mistake and sprayed on a day they shouldn’t have.”

ROLLING IT OUT

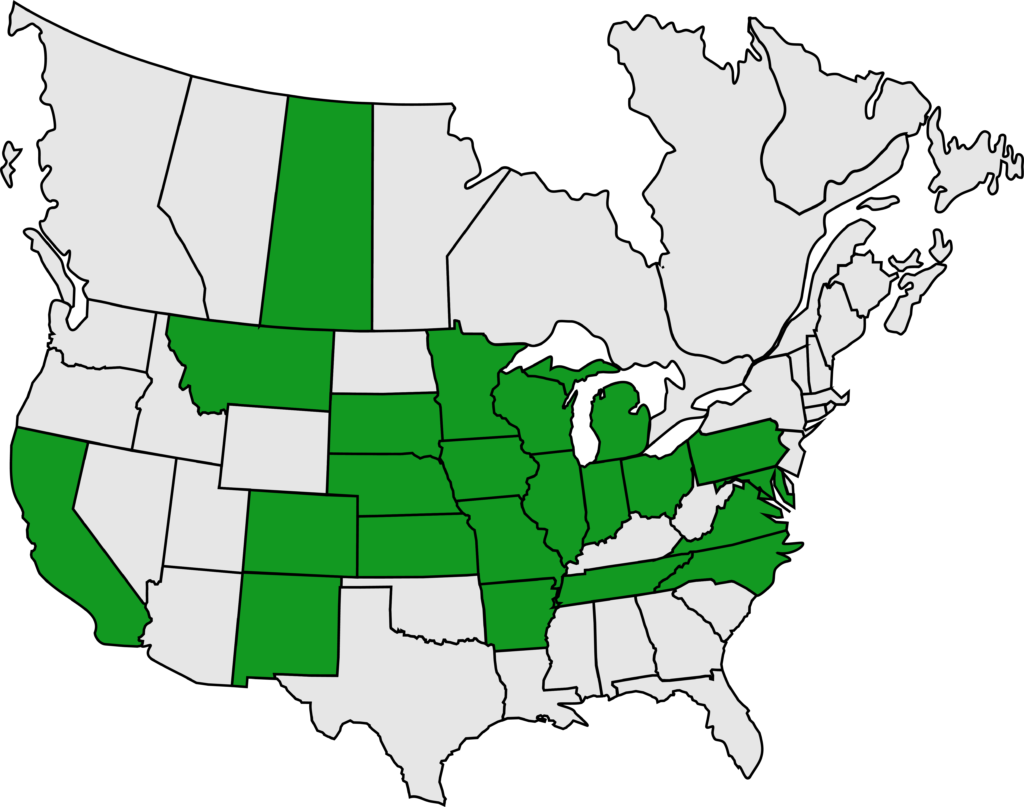

When nearby states became interested in being part of the program, Purdue decided to spin the program off as a nonprofit in 2012, expanding it in both scope and reach. It was renamed FieldWatch, which serves as an umbrella for DriftWatch and newer programs.

About six years ago, BeeCheck came online for pollinators. The tool allows beekeepers to map their hives and provide contact information so that pesticide applicators can coordinate to ensure pollinator safety.

Cybil Preston, a beekeeper and chief apiary inspector for the Maryland Department of Agriculture, said beekeepers in her state have flooded the map with hive locations since joining about a year ago. With honeybee populations declining nationally, they view BeeCheck as another valuable tool for protecting their hives.

“It opens the line of communication between all parties involved. That kind of communication is what I religiously talk about,” Preston said.

Since then, FieldWatch has added CropCheck for row crop producers and FieldCheck, where applicators go to view all data – row crops, specialty crops and apiaries. In all, the FieldWatch programs reach 22 states and one Canadian province with more expansion on the horizon.

There are more than 30,000 individual FieldWatch users who have added more than 37,000 different fields or apiaries to the maps. Growers have added more than 1.3 million acres to the program, and that is expected to grow significantly since CropCheck, the row crop program, was only recently added.

Stephanie Regagnon, FieldWatch president and CEO, said one thing that’s made FieldWatch so successful is that it is completely voluntary in nature. This isn’t a government mandate or another regulation imposed on the agriculture industry.

“It has been a challenge at times because people can misunderstand that,” Regagnon said. “And while FieldWatch is no silver bullet solution to stewardship, when used properly by all parties it can be an extremely effective communication tool. For all of us to play nice in the sandbox, we all have to be in the sandbox. This brings people together to talk with each other.

“If you just start there, knowing that no one wants to have a problem, then you realize that systems like this, that are voluntary in nature and are built on good faith, you find success,” she said.

Users can register their crops and apiaries, and access all the FieldWatch maps for free. Those who want to support the nonprofit can become dues-paying members, which comes with recognition, an invitation to the FieldWatch annual meeting and other incentives.

ALL AT THE TABLE

Another key to FieldWatch’s success is that it balances the needs of all parties. Crop producers, pesticide applicators, chemical manufacturers and other key stakeholder groups make up the board of directors, bringing together people who might not always come together so easily.

“We’ve really been able to keep the three different stakeholder groups – growers, beekeepers and applicators – engaged and building trust. There’s nothing else out there really like it” Regagnon said.

Elisha Kemp, state government and industry affairs leader for Corteva Agriscience, which has a seat on the FieldWatch board, said the program’s balanced approach was an easy draw for her company.

“We appreciate how the board was designed to be balanced. It’s not just applicators or companies like us,” Kemp said. “The representation and broad coverage from all the different stakeholder groups makes it unique and successful.”

Besides the obvious “good neighbor” appeal of the program, FieldWatch is good business for manufacturers and applicators. The more that off-target drift incidents can be reduced, the fewer regulations and rules they and their customers are likely to have imposed upon them.

“Farmers strive to do a good job so restrictions may not always be the best solution,” Kemp said. “When applicators and farmers are aware of their surroundings, that can help with management practices. Having more information is always better.”

Smith said the spirit of farmers working together to reduce drift incidents has certainly crossed into the FieldWatch boardroom.

“We all have a stake in the game,” Smith said. “You might have people around the table with different goals, but everybody’s mission is to not have off-target movements. It’s satisfying to see what’s happened with FieldWatch. It’s just confirmed that a good idea and doing the right thing can actually be popular.”