Great-great-granddaughter of American Soybean Association co-founder embraces 100-year legacy

"Early one morning, when my grandpa was just a young boy, his family traveled to the train station in Camden, Ind.,” said Claire Crum, retelling her favorite story. “There, he saw men shoveling our family’s soybeans into a fancy train. Someone in an expensive-looking suit walked up to my grandpa and shook his hand.”

"Early one morning, when my grandpa was just a young boy, his family traveled to the train station in Camden, Ind.,” said Claire Crum, retelling her favorite story. “There, he saw men shoveling our family’s soybeans into a fancy train. Someone in an expensive-looking suit walked up to my grandpa and shook his hand.”

The man was Henry Ford, who was interested in this new, rare crop. “Mr. Ford toured our farm and shared lunch before returning home with three train cars full of soybeans. He originally intended to use them as a fuel source but instead used them in the black paint of his Ford cars.

“I grew up on stories like this," said Crum, whose great-great-grandfather was among the first farmers to grow soybeans in the United States. “When I was growing up, I knew it was a big deal, but now I realize that everyone uses soybeans every day.”

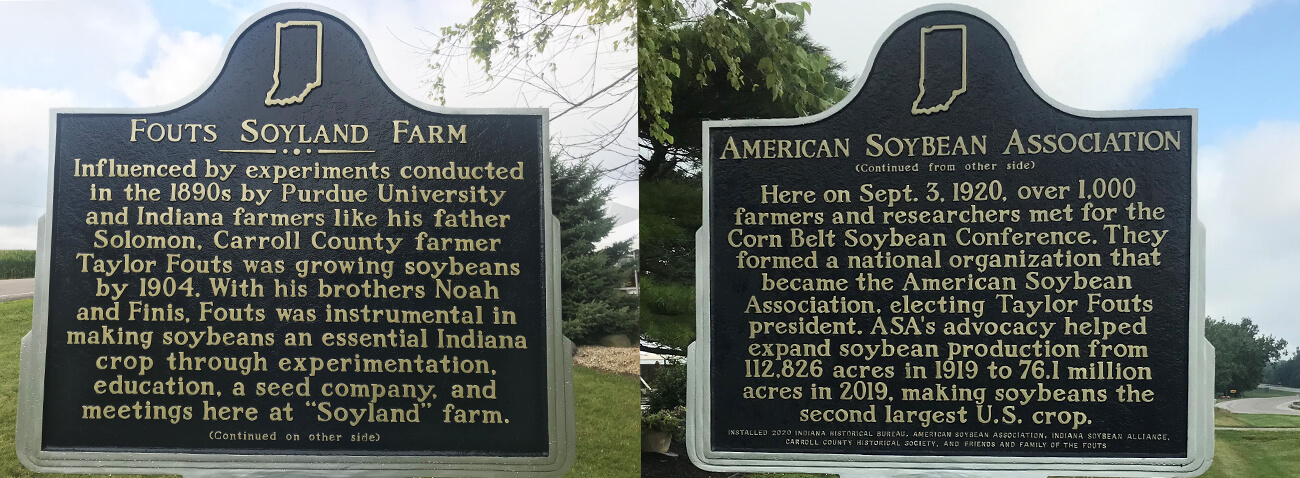

In 1896, Solomon Fouts began to experiment with soybean seeds. At the time, no American farmers grew the crop at scale, but he was intrigued by their potential. Fouts planted the seeds with his sons Taylor, Finis and Noah.

After several unsuccessful seasons, Taylor Fouts, the youngest son, started classes at Purdue. Taylor worked closely with the professors and returned home in 1902 with new ideas. Purdue continued to work with Taylor Fouts and asked him to join a sponsored study to grow soybeans.

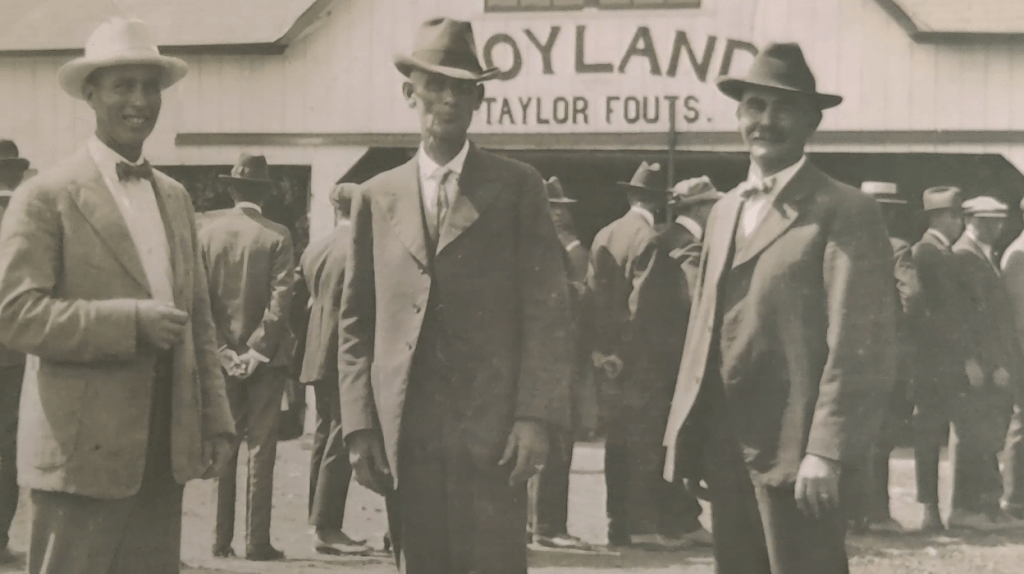

Four years later, Taylor Fouts invited his brothers to join him in the endeavor. Crum’s great-great-grandfather, Finis, was the first to succeed. He helped his brothers replicate the results. Over the next decade, word of the brothers’ windfall spread.

Taylor, Finis, and Noah Fouts

On September 3, 1920, the Fouts brothers hosted a national field day to share their expertise with 1,000 farmers. That day, the National Soybean Growers’ Association was formed. Taylor Fouts was elected the first president of the organization, which was later renamed the American Soybean Association (ASA). A century later, the ASA represents over 300,000 farmers.

“After years of hearing these stories I began to realize the things the Fouts brothers did were radical,” said Crum. “They discovered new uses for soybeans and originated ways to plant, collect, process, and store them. Modern tools weren’t designed to plant and harvest soybeans so they had to be inventive and create their own. Among them was the forerunner to the combine. The Fouts brothers were pioneers.

100th Overview History

“If Purdue hadn’t given him those beans, who knows what farming would look like today,” mused Crum, who attended Purdue like many of the brothers’ descendants. In May, she completed a master’s in agricultural sciences education and communications (ASEC).

“When I walk across campus I find myself thinking about how different it must look from when Taylor was there and how large of a role Purdue played in the history of our family and soybeans.”

While a student, Crum worked closely with her advisor, Natalie Carroll. “Claire was a delight,” said Carroll, a professor of ASEC and agricultural and biological engineering (ABE). “Not only did she bring a strong knowledge of agriculture, she always wants to learn more, and has a passion for sharing her knowledge with others.”

Crum spent two summers as an intern at the Indiana State Fairgrounds while working on her graduate research project. She surveyed fair-goers to better understand consumers’ food choice selections, needs and information sourcing. Crum says the results will help her as she works toward her goal of becoming an Extension educator.

“I love seeing kids’ faces when you tell them something new about agriculture. It fills me with joy. So many don’t understand where their food comes from. I think it is fun and important to take an active role in that farm-to-fork pathway.

“I’m so proud of our family for continuing to do their part generations later,” said Crum. “Looking at the progress of the ASA, Purdue, and our family over the past 100 years, I am tickled pink to think about what my grandpa and his grandpa would say if they were still here."