Food survey: Consumers trust and value product labels

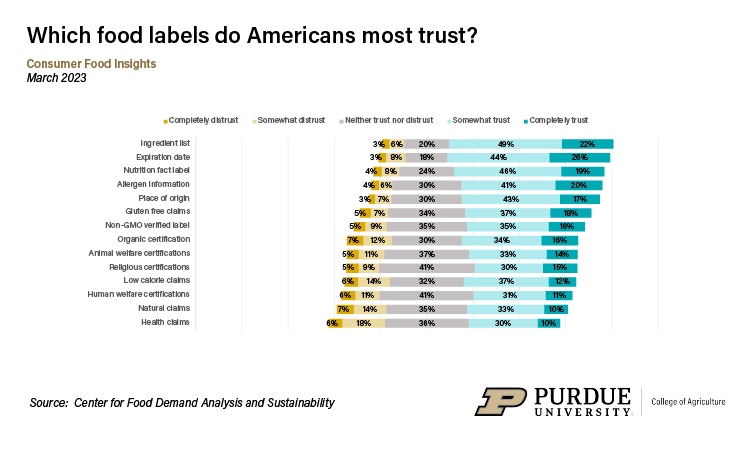

Americans tend to trust food labels, especially the ingredient list, expiration date and nutrition fact label, according to the March Consumer Food Insights Report. The most distrusted labels include low-calorie, naturalness and health claims.

The survey-based report out of Purdue University’s Center for Food Demand Analysis and Sustainability assesses food spending, consumer satisfaction and values, support of agricultural and food policies, and trust in information sources. Purdue experts conducted and evaluated the survey, which included 1,200 consumers across the U.S.

“Generally, consumers trust — or, at least, don’t distrust — the labels on their food. This trust is significantly lower for claims about the health or naturalness of food, claims which may often be more nebulous or more clearly motivated by marketing objectives,” said Jayson Lusk, the head and Distinguished Professor of Agricultural Economics at Purdue, who leads the center.

Utilitarian labels appear to be viewed more favorably. These labels are also the most important to consumers, according to the report.

Share of Consumers who Trust Food Labels, Mar. 2023

Share of Consumers who Trust Food Labels, Mar. 2023 “Among these important labels, the ingredient list and nutrition fact label are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, while expiration dates are not,” Lusk said. “Considering that of all of the information on a food product, the expiration date is one of the primary labels that consumers read, there is an important conversation to be had about standardizing this information.”

More in-depth responses to the new food-labeling questions will appear in next month’s report. This month’s report also looks at the employment status of respondents, comparing adults of working age and of retirement age.

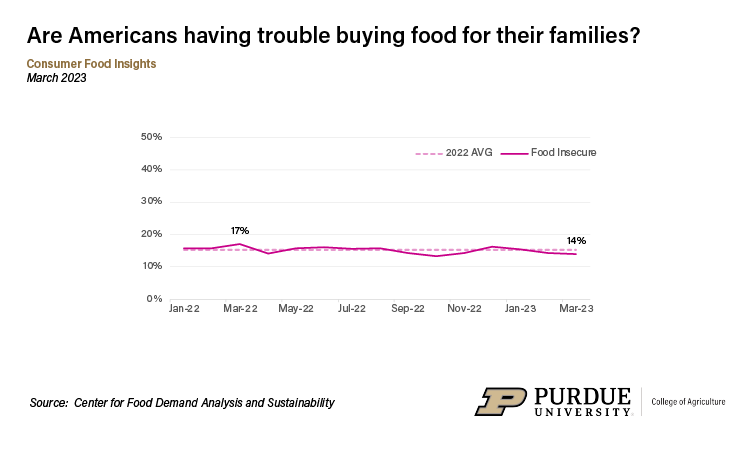

The report’s month-to-month food insecurity rate remains effectively unchanged at 14%. Lusk called attention, however, to the 27% of adults who are not working and who are facing some degree of food insecurity, compared to 12% among those with a job.

Rate of Household Food Insecurity in Last 30 Days, Jan. 2022 - Mar. 2023

Rate of Household Food Insecurity in Last 30 Days, Jan. 2022 - Mar. 2023 “This finding is not surprising, but it drives home the point that more people losing their jobs in the event of a recession could lead to a precipitous drop in the number of food-secure households,” Lusk said. The incredibly low rate of food insecurity among 65-plus households also demonstrates how people generally accrue a number of advantages through their lives, and those who make it to old age also enjoy fairly robust entitlement programs.”

Additional key results from this month’s report include:

- 13% of consumers experienced a stockout, or absence, of one or more items at the grocery store, down from 22% in January.

- Total food spending is up 5% from this time last year, while food inflation expectations for the next year sit at around 4%.

- Unemployed adults have the lowest rates of diet happiness, while retirees have the highest.

- Unemployed adults less readily pursue food behaviors that are viewed as sustainable or ethical.

Consumers are accurately perceiving a slow decrease in food inflation, noted Sam Polzin, a food and

agriculture survey scientist for the center and co-author of the report.

“Though their estimate of 7.1% remains below the official government figure of 9.5% for February, both estimates of inflation are following similar trends,” Polzin said. “Part of continuing to see inflation decline will depend on securing food supply.”

As egg shortages struck the country in December and January, consumers experienced the rate of grocery stockouts to jump along with the consumer estimate of inflation.

“We will continue to feature this stockout measure, as we see it as a unique indicator of the food supply,” he said.

Similar to the food security story, Polzin attributed some of the differences in food satisfaction to income factors as well as life-cycle explanations. While the reasons for this are unclear, other measures of general happiness show it dropping as people enter adulthood and middle age before rising again in old age.

“However, there does appear to be some discrepancy in our data between rates of diet happiness and life happiness, except for among retirees, which opens up some interesting questions about how these two concepts are related,” Polzin said.

Lusk and Polzin also noted differences between employed and unemployed adults. This begins with how often they eat at home versus eating out. They would expect those who work regularly and presumably have a higher income to change their food consumption.

“The behaviors of retirees are also fairly different from every other group, which raises a lot of interesting questions about what changes when someone leaves the labor force,” Polzin said. “There is other research showing that behaviors like healthy eating can decline after retirement. We would like to investigate this demographic segment further.”

Lusk further discusses the report in his blog.

The Center for Food Demand Analysis and Sustainability is part of Purdue’s Next Moves in agriculture and food systems and uses innovative data analysis shared through user-friendly platforms to improve the food system. In addition to the Consumer Food Insights Report, the center offers a portfolio of online dashboards.