Research Looks at Changes in Lake Michigan Nearshore Fish Assemblage

How has the nearshore fish assemblage in Lake Michigan changed over the last 40 years and what does that mean in terms of environmental/habitat impacts?

Dr. Tomas Hook, director of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and professor of aquatic sciences, was part of a recent publication “Nearshore Fish Assemblage Dynamics in Southern Lake Michigan: 1984-2016,” which addressed that topic, specifically looking at nearshore fish in southern Lake Michigan. Hook was a co-author along with former postdoctoral researcher Dr. Chris Malinowski, now the director of research and conservation for Ocean First Institute, and Dr. Jason Doll, assistant professor at the Freshwater Ecology Center at Francis Marion University.

“While others have examined how the offshore food web in Lake Michigan has changed, the nearshore has received less attention,” Hook explained. “There are various reasons to think that nearshore fish assemblage may not track offshore patterns. Tracking how biological communities and assemblages change can be an informative way to assess environmental impacts. Communities can reflect the integrative effects of various stressors on a system.”

The publication states the reasoning for the study:

“Given that multiple stressors often concomitantly impact ecosystems, it may be difficult to disentangle which stressors are most influential. Upper trophic level communities, such as fish assemblages, can provide insights to the influence of diverse stressors as they may integrate cumulative effects over the long-term and also reflect responses of lower trophic levels.”

Research showed that fish assemblage in southern Lake Michigan has changed over time, and most notably, that the abundance of fish has decreased, and that the overall species richness and native species richness have declined. There have been some dramatic declines in some small-bodied native fish, such as johnny darters, and also a decline in yellow perch. The data also documented the invasion and subsequent expansion of round goby.

These patterns are similar to offshore fish assemblage and likely reflect responses to invasive species (including quagga, zebra mussel and round goby) as well as an overall decline in system productivity related to decreased nutrient loading.

These patterns are similar to offshore fish assemblage and likely reflect responses to invasive species (including quagga, zebra mussel and round goby) as well as an overall decline in system productivity related to decreased nutrient loading.

“Many people think of decreased nutrient loading as a positive, but in rather unproductive systems like Lake Michigan, decreased nutrient loading may contribute to decreased biomass of fishes,” Hook noted. “This study is an example of the value of long-term monitoring of natural systems. Going out and collecting the same type of data over and over each year takes a lot of money and effort. It may not be clear what such monitoring will lead to as each year of monitoring data on its own doesn’t generally result in novel finding or publication. However, if we don’t continue to collect these types of long-term data, informative, retrospective analyses are not possible.”

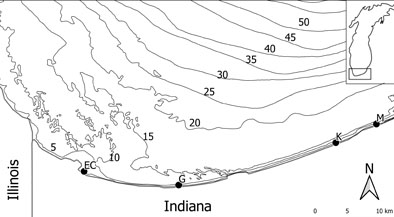

For this study, long-term monitoring was funded by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources and carried out by Ball State University, including Tom Lauer, a former Ball State professor and FNR alumnus. Fish were collected from three sampling sites located in the Indiana waters of Lake Michigan. The sites are characterized as extreme near-shore shallow sites with primarily flat, sandy bottom, with undulating sand and clay ridges.