Simulations show how beta-amyloid may kill neural cells

Beta-amyloid peptides, protein fragments that form naturally in the brain and clump into plaques in Alzheimer’s disease patients, are thought to be responsible for neuron death, but it hasn’t been clear how the substances kill cells. Now, a Purdue University scientist has shown through computer simulations that beta-amyloid may accumulate to kill neural cells by boring holes into them.

The findings are the first to show how beta-amyloid forms the pores that kill neural cells in patients afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease and suggest targets that could offer new treatments.

Ganesan Narsimhan, professor in the Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, uses simulations to understand how antimicrobial peptides produced by insects protect them against harmful microorganisms. He’s found that these antimicrobial peptides form aggregates and bore into the cells of foodborne pathogens, creating pores that allow intracellular fluid to leak, thereby, killing the cells and alleviating the threat of food poisoning. Since proteins and peptides are normal constituents of all foods, that work holds promise for creating “green” food safety products, such as sprays for fresh produce and packaging films.

Narsimhan knew that antimicrobial peptides had to form small clusters in order to kill pathogenic cells, and he noticed that while beta-amyloid alone does not cause cell death, formation of beta-amyloid aggregates could. He set out to determine whether beta-amyoild and microbial peptides functioned in similar ways to kill cells.

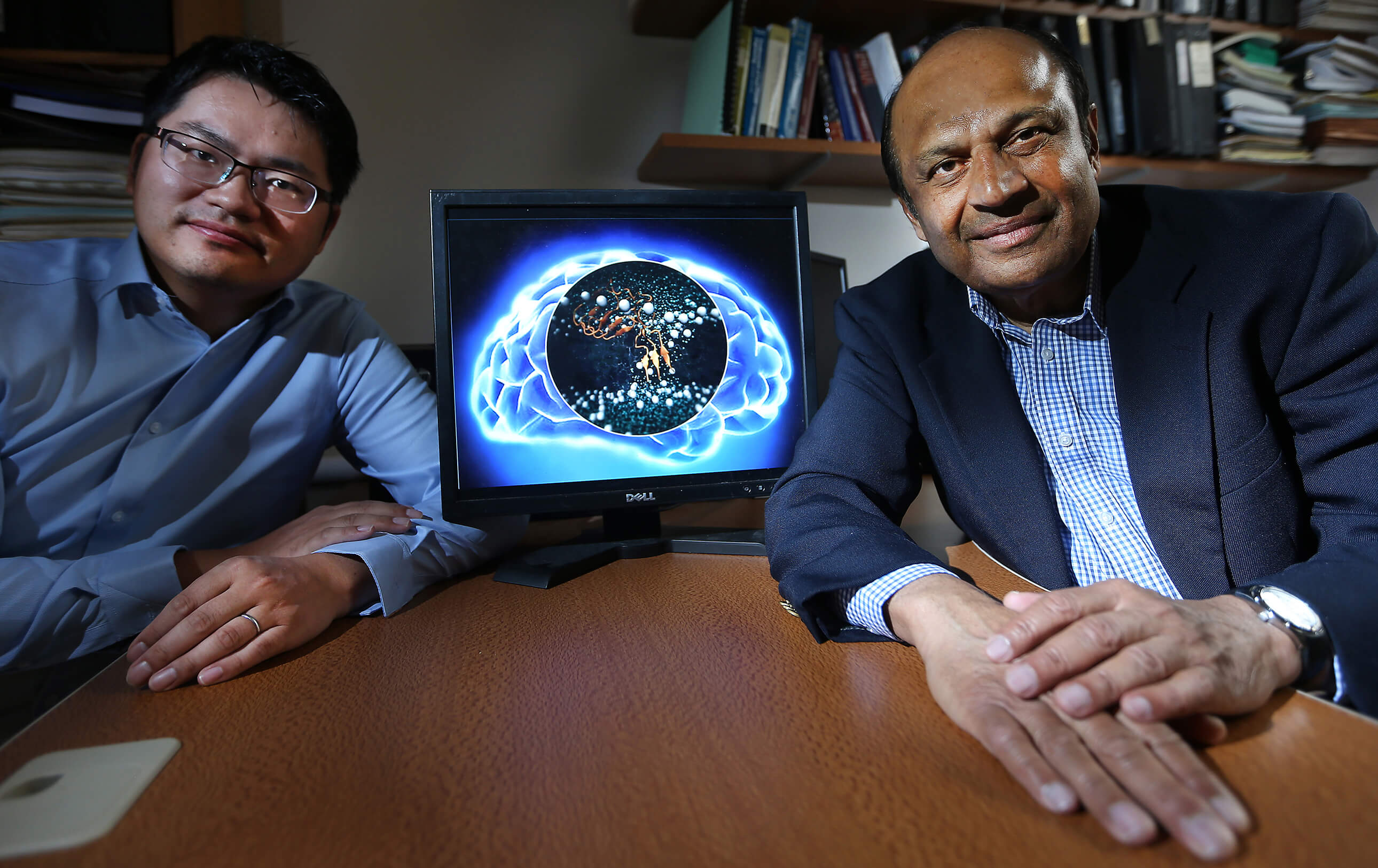

Narsimhan focused on Aβ 1-42 since an imbalance in the concentration of this peptide is associated with Alzheimer’s cell death. In collaboration with Xiao Zhu, a senior research scientist for Information Technology at Purdue Research Computing, Narsimhan’s research group performed computer simulations showing that a single Aβ 1-42 peptide had no effect on neural cells, but in groups of three or five, called oligomers, they are able to penetrate the cell membrane and form small pores and kill the neural cells.

“The aggregation of these peptides is a precursor to penetration of the neural cell, leading to the formation of a pore,” said Narsimhan, whose findings were published as the cover story in the March issue of the journal Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. “This demonstrates that formation of an aggregate is an essential step in the penetration and formation of pores leading to neural cell death. That’s what happens in Alzheimer’s disease.”

Simulations of other beta-amyloid peptides and experiments are necessary to confirm the significance of these findings in the brain. But the work suggests that neural cell death in Alzheimer’s disease could be slowed or stopped with therapies that inhibit formation of these toxic beta-amyloid peptide aggregates.

“The cure or therapy to Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases may lie in preventing formation of oligomers in the fluid within the brain,” Narsimhan said.

Computational resources for the research were provided by the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment.