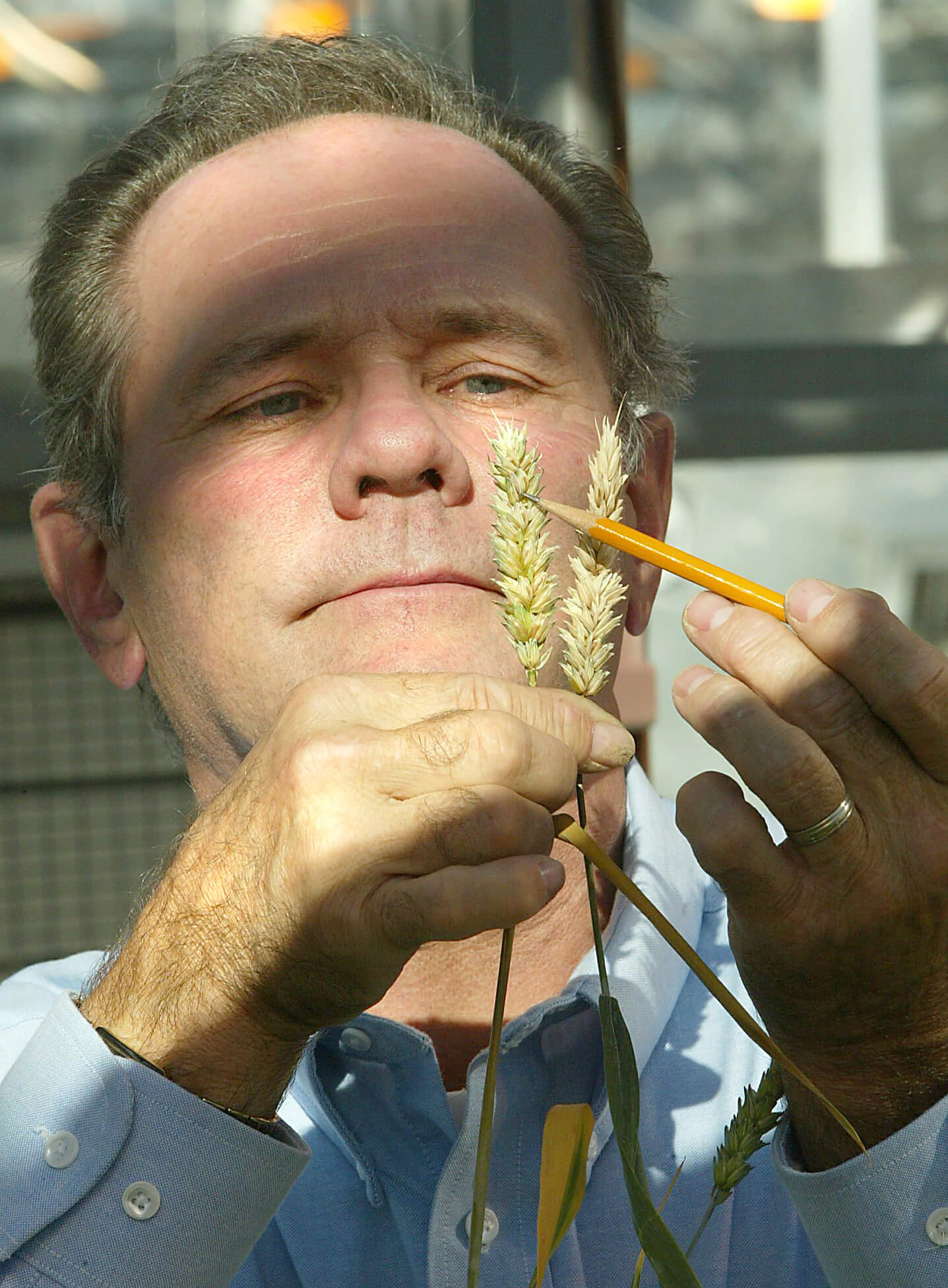

Purdue’s Herb Ohm sees decades of work come to fruition

H

erb Ohm had no intention of retiring in 2014. He still had work to do and, by his own calculations, he’d be in the field and lab for at least another three years when he would turn 70.

After earning his doctorate under famed Purdue wheat breeder and agronomist Fred Patterson, Ohm joined the Purdue faculty in 1971, eventually becoming the leader of the wheat-breeding program when Patterson retired in 1986. One of Ohm’s specialties was crossing wheat with wild and exotic species that contained genes long left behind by those who had cultivated modern wheat varieties. The hope was that those exotic species have natural genetic resistance to pests and diseases.

“That was very frustrating to me. This severe stroke came and totally turned my life upside down,” Ohm said. “Because of this, I had to retire and eventually or gradually lost contact with my collaborators and other faculty in my department at Purdue.”

THE WORK LIVES ON

It was the end of Ohm’s involvement in wheat genetics, but it wasn’t the end of his work.

From 2000 to 2008, Lingrang Kong had worked with Ohm as a postdoctoral researcher and a research geneticist in the Department of Agronomy. After becoming a professor in wheat breeding and genetics at Shandong Agricultural University in China, Kong took up his mentor’s work and led the effort to identify the gene responsible for fusarium head blight resistance.

For nearly two decades, leading up to 2012, Ohm’s lab had been making cross after cross of exotic wheat species with commercial varieties until they found one that imparted strong resistance to fusarium head blight. They were actively characterizing those plants and beginning to identify the gene or genes responsible.

Maybe Ohm would have gotten much of this done in the three remaining years he planned to work, or maybe he would have followed in Patterson’s footsteps again and retire but continue coming in for many years after.

That decision was taken out of Ohm’s hands when, in April 2012, he suffered a severe stroke. Despite efforts to return to his work, he was forced to retire a year later.

This week, seven years after Ohm had to step away from his research program, Kong’s team published its findings in the journal Science. In the list of authors, right before Kong’s name, is Herbert Ohm.

Kong also sent Science a piece that reflected on Ohm’s influence.

“As my supervisor, Dr. Ohm was humble and sincere with others. I learned a lot from Dr. Ohm on both a personal and professional level,” Kong said. “His actions have had a profound influence on me.

“Dr. Ohm’s encouragement enabled me to continue this project,” Kong added. “It would have been hard to publish this article in the journal Science without Dr. Ohm’s continuous support.”

In the paper, the authors report that they’ve identified and isolated the gene Fhb7 from Thinopyrum elongatum, a wheatgrass native to Africa and Eurasia. It shows a similar effect on resistance as Fhb1, one of the few known genes that imparts any resistance to fusarium head blight.

The team was able to clone Fhb7, and characterize and describe the mechanisms the gene uses to impart resistance. But one of the most significant findings is that inserting Fhb7 into a wheat line makes no other agronomic changes to the plant and causes no yield penalty. Breeders who incorporate Fhb7 won’t be trading yield for disease resistance.

“Before, the genes weren’t isolated sufficiently. The nice thing here is that we’ve identified a single gene, and that can be transferred in with the proper genetic markers,” Ohm said. “I think farmers can get the same performance in terms of yield and other traits from wheat that has good resistance to fusarium now.”

The Fhb1 gene imparts only a partial resistance to fusarium head blight, said Joe Anderson, an Ohm colleague and professor of agronomy at Purdue. Adding Fhb7 significantly increases resistance and will save farmers from significant losses.

“This gene is one of the few strong enough to add a significant additional level of resistance when combined with Fhb1,” Anderson said. “This is an important tool wheat breeders now have in their toolboxes.”

The authors also note that the gene is otherwise unknown in the plant kingdom but is 97 percent similar to a genetic sequence with a fungus called Epichloë aotearoa, which infects some grass plants. That suggests wheat obtained Fhb7 through horizontal gene transfer — the passing of genetic material between two organisms without reproduction — which occurs rarely. It makes finding it all the more significant.

“This is not as simple as finding an important wheat gene in exotic germplasm,” said Mitch Tuinstra, Ohm’s former colleague and a Purdue professor of plant breeding and genetics, Wickersham Chair of Excellence in Agricultural Research and scientific director of the Institute of Plant Sciences. “The fact that it’s not even a wheat gene but begins in an exotic endophyte is fascinating. This research is the product of decades of wheat breeding and efforts to incorporate exotic wheat germplasm into modern wheat.”

PERSISTENT DEDICATION TO THE WORK

Tuinstra could well have said generations of work. Kong’s decade-plus of work followed Ohm’s 40-year career. Ohm took the reins from Patterson, who spent 36 years as a preeminent wheat breeder at Purdue, credited with developing more than 50 varieties of wheat, oat and barley, and increasing farm income more than $3 billion. Purdue named an endowed chair position for Patterson in 2004.

Ohm followed Patterson with similar zeal and intensity. The same year the university recognized Patterson with an endowed chair, Ohm was named a distinguished professor. He developed 37 wheat cultivars, including varieties resistant to yellow dwarf disease and fusarium, and 10 types of spring oats.

Anderson credits Ohm’s approach with students and postdoctoral researchers for allowing Kong to see the project through. Ohm wanted students well-versed in genetic approaches to breeding, but he also wanted them out in the field doing the hands-on work of traditional plant breeding. He also believed in taking the long approach to breeding, spending years to use exotic species and making sometimes dozens of crosses to distill the offspring into varieties that would have a desired trait.

“This paper demonstrates his scientific acumen, his forward thinking in terms of bringing in resistance genes from a wide variety of related species. It takes years and years to go through that process, and he was willing to spend a significant portion of his program doing that,” Anderson said. “And to have that gene identified that can be transferred into new cultivars and varieties that farmers can use around the world will bring joy to Herb. That’s what he was all about. He was trying to develop materials that would benefit the farmer.”

It’s a legacy his former colleagues are happy to see in the pages of one of the world’s premiere academic journals.

“Herb hasn’t touched this material in 10 years, but he’s on the author list. What that says is how highly regarded he is by his former students and postdocs,” Tuinstra said. “Lingrang Kong didn’t forget where this came from and wanted to make sure Herb’s contributions were included in this paper.”

That’s not lost on Ohm, who has counted Kong as a long-time friend.

“It’s gratifying to see this paper come out,” Ohm said. “Kong is a good researcher. I’m glad that he continued to be involved in and work on fusarium resistance in wheat.”