Purdue group prominent in studying chemical compounds that are everywhere — and shouldn’t be

As interest in “forever chemicals” increases, a Purdue group in Discovery Park’s Center for the Environment emerges as a preeminent team researching them.

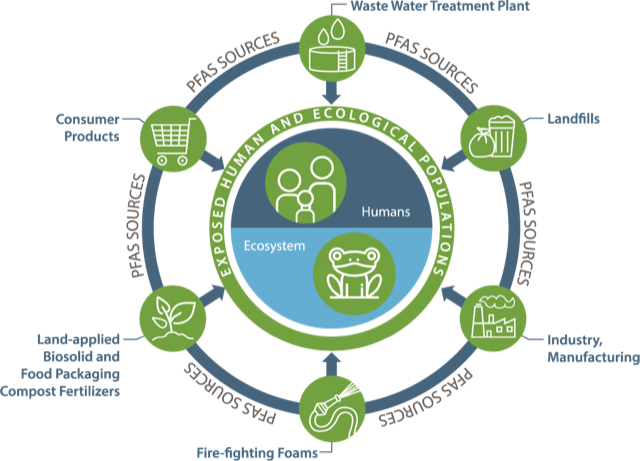

At first glance, a pizza box, raincoat, nonstick pan and firefighting foam don’t have much in common. But a group of researchers in the Center for the Environment at Purdue wants us to understand that in using these seemingly unrelated products, we introduce chemicals into the environment that may linger for millennia — and in the shorter term, affect animal and human health.

They’re called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Purdue is front and center on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s “aggressive and unprecedented efforts to address PFAS in the environment” as detailed in the EPA’s PFAS Action Plan released earlier this year. Grants to center affiliates from the College of Agriculture and College of Health and Human Sciences to fund PFAS research reflect this federal priority.

Manufacturers in the U.S. and around the world have used PFAS since the 1940s. Of more than 4,000 such substances, only two have been studied extensively. Scientists found that they don’t break down, earning them the moniker “forever chemicals.”

PFAS are in your home, school and workplace. They’re in food, commercial household products, drinking water, and living organisms, including fish, animals and humans. Although the Indiana Legislature recently approved a bill limiting the use of firefighting foam containing PFAS, they remain largely unregulated in Indiana.

Professor of Agronomy Linda Lee’s lab was among the earliest to focus on behavior of these compounds and measurement of PFAS levels. “What I learned after about five years is that this is a big problem, and a lot of people need to be working on it if we’re going to make any headway,” Lee says. “I understand how these chemicals behave, but different aspects of the problem demand different expertise.”

Over time other scientists became involved in PFAS research. Today the interdisciplinary team includes: Maria (Marisol) Sepúlveda, professor of ecology and natural systems, forestry and natural resources; Jennifer Freeman, associate professor of toxicology, College of Health and Human Sciences; Jason Hoverman, associate professor of vertebrate ecology, forestry and natural resources; and Jason Cannon, associate professor of toxicology, College of Health and Human Sciences.

In their own labs, and in collaboration with each other and with government and industry partners, these researchers are advancing understanding of PFAS and their impact on the ecosystem. Moving forward, engineering expertise will be critical to developing PFAS remediation and mitigation technologies. “We’re starting to get traction on that now,” Lee says.

The PFAS group is a good example of how the Center for the Environment functions, says its managing director, Lynne Dahmen. The center supports faculty university wide working to solve environmental challenges. “We work with interdisciplinary faculty teams, help them coalesce, assist in grant development and help promote their work,” Dahmen explains.

“Environment-related problems involve disciplines from all over campus,” Lee says. “We needed a bridge, not another department —and that what’s the center is about.”

Funding opportunities for PFAS research were once slim, she notes. Then the chemicals’ widespread use in firefighting foams at U.S. military training centers prompted the Department of Defense to offer funding to explore how exposure impacts human health. The EPA, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, U.S. Agency for International Development, National Academy of Sciences, National Science Foundation, and nonprofit Water Research Foundation have followed suit with different questions about PFAS. “This one group of chemicals is receiving a lot of attention for the right reasons,” Marisol Sepúlveda says.

Attention in this case translates into dollars — more than $1.7 million in research grants in FY2020 to members of this team to study PFAS’ impact on drinking water, wildlife populations, agricultural ecosystems, air and human health. This month the EPA awarded $3.2 million to Purdue and Indiana University for PFAS research, including $1.6 million to a team Lee is leading for field, laboratory and modeling activities that investigate PFAS in private drinking wells and water resource recovery facilities in rural communities.

The Purdue researchers are emerging as a preeminent team investigating and publishing on forever chemicals.

Lee’s current research quantifies the chemicals in drinking water, wastewater and biosolids, and shows how PFAS are transported into the soil, groundwater and crops when biosolids are applied to agricultural land. Her work helps establish decision tools and management guidelines for agricultural and industrial settings.

Freeman studies how PFAS impact the endocrine and central nervous systems in zebrafish, laying the groundwork for expansion into human epidemiology. With grant funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) one of Freeman’s projects focuses on the neurotoxicity of PFAS mixtures in firefighting foams.

Sepúlveda investigates how PFAS chemicals bioaccumulate in tissues of wild animals; how different animals respond; how a species responds in different life stages; and adverse effects of PFAS accumulation.

Hoverman takes a wider view of animal populations, studying the effects of PFAS contamination on freshwater ecosystems. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources recently funded his research to assess ecosystem-level effects of PFAS contamination on wetland food webs.

Cannon researches PFAS in the brains of nematode, amphibian and rodent models to explore possible links between these chemicals and human neurodegenerative diseases.

Such diversity in the team members’ expertise is often an asset on grant applications. For example, in collaboration with Hoverman and Lee, Sepúlveda leads a five-year, Department of Defense-funded project to develop PFAS toxicity reference values for amphibians.

Her work, she says, depends on Lee’s chemical analysis. “The way PFAS exert their toxicity is not well understood,” Sepúlveda says. “We have to put the chemistry and toxicology together.”

As the veteran of the group, Lee is heartened that her colleagues bring the interdisciplinary perspectives that will be needed to solve complex PFAS problems. “Now they’re able to take the lead in proposals,” she says. “The most important thing is to see solutions and progress."