Entomology alumnus combines best of business, education and public service

Like many students of his era, David Mueller (BS ’75, Entomology) was influenced by Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring. “She was one of my heroes,” Mueller says. While he didn’t agree with everything she wrote, Mueller notes that Carson’s work triggered not only the environmental movement but also chemical companies’ support of university research.

“It had a great impact for Purdue in funding and growth of the staff,” Mueller says. “Dr. John Osmun (head of entomology at Purdue from 1956 to 1972 and one of Mueller’s mentors) said there should be a statue of her in front of every entomology department.”

In tandem with his Purdue mentors, the book also influenced Mueller’s career path and advocacy for the use of pheromones in pest management. Board certified in urban and industrial entomology since 1982, Mueller is a longtime member of the Entomological Society of America and 2019 inductee into the Pest Management Professional Hall of Fame. Purdue honors include the 2001 John V. Osmun Alumni Professional Achievement Award in Entomology and the Distinguished Agriculture Alumni Award in 1999.

He first read about pheromones in an entomology department newsletter. “I understood there were communication processes called pheromones, but I didn’t know I would spend 40 years working with them,” he says.

With Osmun’s support, Mueller landed a job with a California fumigation company as its Midwest safety trainer. He observed that the Indian meal moth, a common store product pest, was attracted to a sticky fly trap.

He took his finding to David Matthew, Purdue professor of entomology, who immediately handed Mueller a pheromone trap. “It was like magic,” Mueller recalls. “I couldn’t believe this trapping system could do something like that.” But back in California, his boss rejected its use: “He said, ‘No, we’re not in the pheromone business.’”

Mueller’s response: “’Well, I am,’ and I decided to start my own business.”

In 1981 he founded Fumigation Service & Supply, Inc. and in 1982, Insects Limited, Inc. The two businesses became the foundation for Mueller’s lifelong efforts to provide successful pest management and prevention with fewer chemicals.

Slow and steady won the race for Mueller’s companies. “We’re an overnight success that took 40 years to build,” he says. “We weren’t in the business of taking big risks. I’m not a risk-taker, even though I’m an entrepreneur.”

Like his competitors, Mueller’s businesses relied on products containing methyl bromide, a chemical in use since the 1930s and the go-to standard worldwide for killing pathogens, nematodes and insects. It also was among nearly 100 manmade chemicals named as ozone-depleting substances in the 1987 Montreal Protocol, the landmark environmental agreement that remains the only United Nations Treaty ratified by all 198 UN members.

Mueller was in the audience at a conference in the early 1990s when a NASA scientist offered compelling evidence that the chemical was harming the ozone layer, impacting both humans and plants. At the time, Mueller depended on its use for more than half of his business.

Phasing out methyl bromide would eventually reduce the number of fumigants on the market from more than 30 to two. “But most people were questioning the science and denying the problem,” Mueller says. “A lot of people were protecting their jobs.”

Mueller went home and connected with Purdue researchers to explore alternatives, including pheromones. Their collaboration led the UN to invite Mueller to join a global training team to help phase out the use of methyl bromide and introduce other pest management technologies and techniques.

Fumigating a 25 million cu. ft. baby food factory with a methyl bromide alternative.

Fumigating a 25 million cu. ft. baby food factory with a methyl bromide alternative. Mueller’s UN work took him to more than 40 developing countries in Africa, Asia, South America and Europe. His absences required sacrifices by his family and employees, “but we saw this as something important,” Mueller says.

“Dave’s career is impressive. Having built two Indiana businesses, he traveled the world to help play a role in saving the ozone layer,” says Barry Pittendrigh, John V. Osmun Endowed Chair and director of the Center for Urban and Industrial Pest Management.

Mueller also helped convene a Fumigants and Pheromones Conference that since 1993 has taken the conversation about better pest management with reduced environmental impact around the world. The 14th conference will be held at Purdue — the first time ever — in June 2023 around a theme of Innovation Technology. The agenda will include insights into research in entomology, food science, and agricultural and biological engineering.

The conferences have reflected a shift in his industry over the past four decades, Mueller says. “Let’s go back to Rachel Carson, who said man thought they were conquerors of nature. I believe that over time, that attitude has changed.” The result, he adds, has been industry-wide acceptance of new technologies and approaches to monitoring and controlling insect pests.

Mueller retired four years ago, turning the fumigation company over to his son Pete, a Purdue alumnus, and the pheromone side of the business over to his son Tom. Daughter Francie, an entrepreneur, handles web and marketing functions. “I’m very proud of all three of them,” Mueller says. “I get to sit back and watch them grow the businesses.”

He never misses a chance to let smart, persistent Purdue entomology students know a job is waiting for them. Between retirement travel, fly fishing with his entomology buddies and carving duck decoys, Mueller continues to support Purdue entomology research and education.

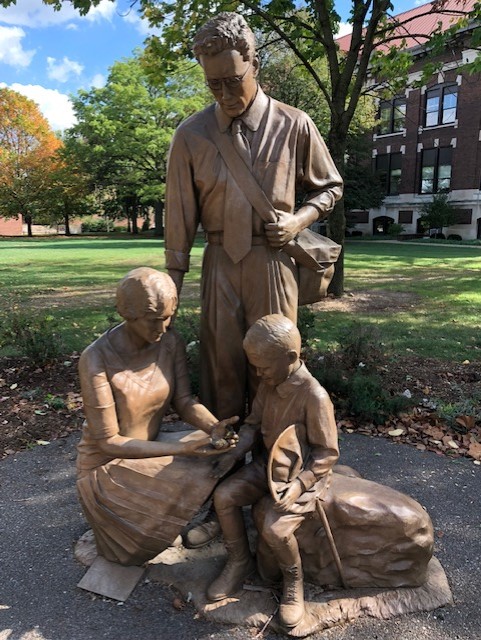

In 2017, Mueller was among the lead donors who helped place the bronze sculpture “The Entomologist” outside the Agriculture Administration Building.

“The Entomologist”

“The Entomologist”