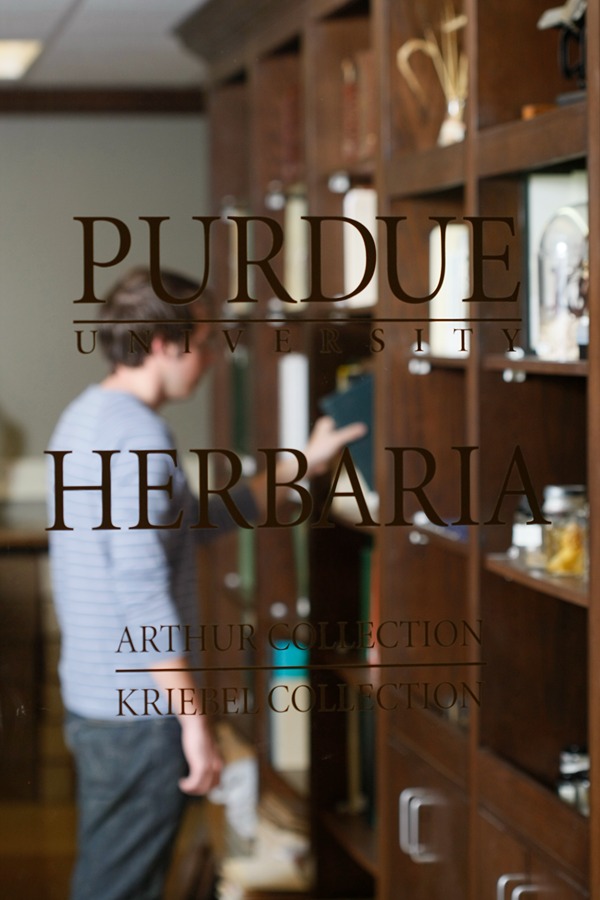

Plant pressings, photo albums and portals into our past

When people have a fire or natural disasters in their homes, the first things they’ll grab are the photo albums. We need to appreciate that our herbaria are our photo albums of natural biodiversity. These samples are essentially our snapshots of Indiana across time.”

- Rabern Simmons, curator of fungi at Purdue University Herbaria

Tall lockers filled with bin boxes and folders packed to the brim with dried plants, fungi and algae don’t seem very sci-fi, but they’re as close as botanists and mycologists can currently get to time travel. They use these portals to the past to explore how the natural world has changed and predict how those patterns might affect us in the face of a climate-change-ridden future.

Despite the importance of these physical links to Earth across the centuries, herbaria across the world are fighting to stay alive. Duke University recently made the decision to shut down their herbarium, one of the largest in the U.S. with over 825,000 specimens.

Catherine Aime, professor of Botany and Plant Pathology, director of Purdue University Herbaria and current president of the Mycology Society of America, has specimens stored in Duke University’s herbarium from her expeditions around the world. She’d like to bring these samples into Purdue’s herbaria, but space and resources are limited.

Catherine Aime, professor of Botany and Plant Pathology, director of Purdue University Herbaria and current president of the Mycology Society of America, has specimens stored in Duke University’s herbarium from her expeditions around the world. She’d like to bring these samples into Purdue’s herbaria, but space and resources are limited.

“The shuttering of Duke’s herbarium is shattering on many levels and sends a terrible message to the academic community that universities don’t see themselves as having a role in preserving knowledge,” Aime said.

Duke University’s herbarium leaders say the closure was caused by insufficient funds. Aime shares what happened at Purdue.

“Purdue’s herbaria had been effectively shuttered for about 20 years. The department head of botany at the time, Peter Goldsborough, fought to create a new position—my position—to preserve the collections,” Aime shared. “Our current battles are mostly centered around trying to get funding to keep the doors open. Everything we do—from mailing loans (and we get a lot of loan requests), to storing specimens, to cyberinfrastructure, to staffing—costs money, and all of this, with the exception of a recently appointed trial curator position, has to be accomplished on soft funds.”

Even though Duke University has committed to sending their specimens to other herbaria, Rabern Simmons, the curator of fungi for the Purdue University Herbaria, explained that this just creates more problems for the greater scientific community.

Simmons, the curator of fungi for the Purdue University Herbaria, explained that this just creates more problems for the greater scientific community.

“My mother, a kindergarten teacher in the maligned Appalachian mountains of Virginia, taught her students more common sense: you don’t put all of your eggs in one basket,” Simmons said. “If we put these specimens in increasingly fewer centralized locations, then we increase the chances of a potential catastrophe leading to the total destruction of these samples.”

Museums, universities and other places that store knowledge are vulnerable to attacks and natural disasters. In 1943, a bomb raid completely destroyed the herbarium and library of the Berlin Botanical Garden.

Keeping herbaria local is also important. Duke University hosted many specimens specific to their North Carolina region. Scientists in the state had access to those samples and could then provide data on local biodiversity trends and patterns. Without convenient access to samples, will biodiversity research in that region continue to the same extent?

One solution in the current digital age might seem clear: scan photos of the samples and log them into a digital database. While Simmons and other herbaria curators are doing this, it's a labor-intensive feat. Moreover, the physical samples have information that cannot be captured in a photo.

Simmons knows the pressings hold answers to questions we don’t even know how to ask, yet. “If someone 50 years ago had written down as much information as they could and taken a photograph of an organism, then thrown it away, that would be all the information that we would have. Now, through our molecular and genomic methods, we can do further analysis on samples collected hundreds of years ago. It’s given us a better appreciation of biodiversity. We have no idea what someone could do with a specimen 50 years from now if we don’t save it today.”

Paula Andrea Gomez-Zapata, a recent graduate from Aime’s lab, is modern proof of this. She studied an orange-colored fungus known as rust that grows on plants. She wasn’t looking at the fungi, but rather insects that feed on the fungal spores. Microscopic, dried insect larvae were still preserved on the pressings of several plants, which allowed her to follow their colonization across time and geography—research that would not have been possible using photographs.

Paula Andrea Gomez-Zapata, a recent graduate from Aime’s lab, is modern proof of this. She studied an orange-colored fungus known as rust that grows on plants. She wasn’t looking at the fungi, but rather insects that feed on the fungal spores. Microscopic, dried insect larvae were still preserved on the pressings of several plants, which allowed her to follow their colonization across time and geography—research that would not have been possible using photographs.

For this reason, Simmons is determined to protect a combined 235,000 specimens from the Kriebel Herbarium and Arthur Fungarium that the Purdue University Herbaria host and also to develop a deeper appreciation for the history they hold. He spends much of his time building educational resources for the herbaria and giving tours to interested students, staff and faculty.

After studying a little-known group of fungi called chytrids—one genus of which were found to be the cause of infections endangering amphibian populations around the world—Simmons is a firm believer in paying attention to the small and underappreciated. “I like to repeat what my mentor Joyce Longcore used to say, ‘You never know when something that is found will become important.’ It would be our own hubris to say that we have done as much as possible with a sample and just throw it in the trash.”

become important.’ It would be our own hubris to say that we have done as much as possible with a sample and just throw it in the trash.”

The herbaria aren’t just gateways to the past. Aime, Simmons and other scientists are constantly adding to the collections at Purdue. The herbarium and fungarium are still producing “snapshots,” recording the present for future botanists and mycologists to discover more about how the natural world works.

Aime said, “Biological collections are living, essential, foundational parts of the biological scientific process. All of us who maintain these collections understand that we are stewards of all the work that came before us to build these collections, and for the future and common good.”