A Bug Bowl History: Where did cricket spitting come from and how fast can a cockroach run?

Purdue’s Bug Bowl has encouraged the public to get up close and personal with insects for three decades. While Bug Bowl will not take place this year after Spring Fest was canceled because of the COVID-19 virus, spring is still a natural time to reflect on the importance of insects and our relationship to them. Plans for the 2021 Bug Bowl, which will be the 30th Bug Bowl, are already underway.

Bug Bowl, a flagship event of the College of Agriculture’s annual Spring Fest, was established 30 years ago and completely by accident.

In the spring of 1990, entomology professor emeritus Tom Turpin was teaching an entry level entomology course for non-majors. Turpin always viewed this as an opportunity to change people’s minds about insects, one of the most misunderstood animal groups on the planet.

In addition to in-class education about the importance of insects to ecosystems, food supplies and the environment, Turpin always hosted several interactive activities for the class ranging from nature walks to movie nights. In 1990, however, Turpin introduced a less traditional element to the curriculum: cockroach racing.

“I don’t quite remember why, but the subject of how fast a cockroach could run came up in this class, and I didn’t know,” Turpin said. “And so we decided to hold a cockroach race.”

And so was born Roachhill Downs, a stadium constructed for the race, where roaches bred in the department were colored to differentiate them and then raced around the track, or, Turpin said, at least an approximation of a race. “As it turns out, it’s incredibly challenging to orchestrate a cockroach race,” he continued.

While the activity was only intended as a class activity, a local radio DJ got wind of the event and made mention of the upcoming race on the air. When the time came for students to lead their mounts to the gate, Turpin said roughly 100 people from the community had gathered to watch the spectacle. And it turned out cockroaches move quite quickly – 2 miles an hour, which is pretty fast when considering their size.

“I had two reactions to that initial turnout,” Turpin said. “First of all, there must not be much to do in Greater Lafayette. But second, if you package it right, people would actually be interested in engaging with insects in a fun way.”

Next year Turpin and several colleagues organized an event with the intention of bringing the community to Purdue, showing them a good time and slipping a bit of scientific research and insect appreciation in between all the novelty events.

Gwen Pearson, entomology outreach coordinator and Bug Bowl organizer, said, “The philosophy really has always been a spoonful of fun makes the science go down.”

The impromptu bug bowl in 1990 sparked a concerted effort by entomology the following year to establish a department sponsored Bug Bowl. Over its three decades, the event has morphed but always maintained a focus on engaging and educating the public about insects.

“I think people don’t always realize that insects have a job to do,” Pearson said. “If you don’t want them in your home, that’s fine, but leave them outside, don’t disturb them in their natural habitats. A lot of people don’t like millipedes, although those are arthropods, because of all their legs, but those are the original recyclers, taking everything on the ground and making beautiful soil from it.”

"If you package it right, people would actually be interested in engaging with insects in a fun way.”

Fear of insects largely stems from ignorance or exaggeration fueled by media and entertainment villainizing them. And, over the years, Turpin said, he has seen people’s minds change about insects both during the course of the event and year after year as they return, families in tow.

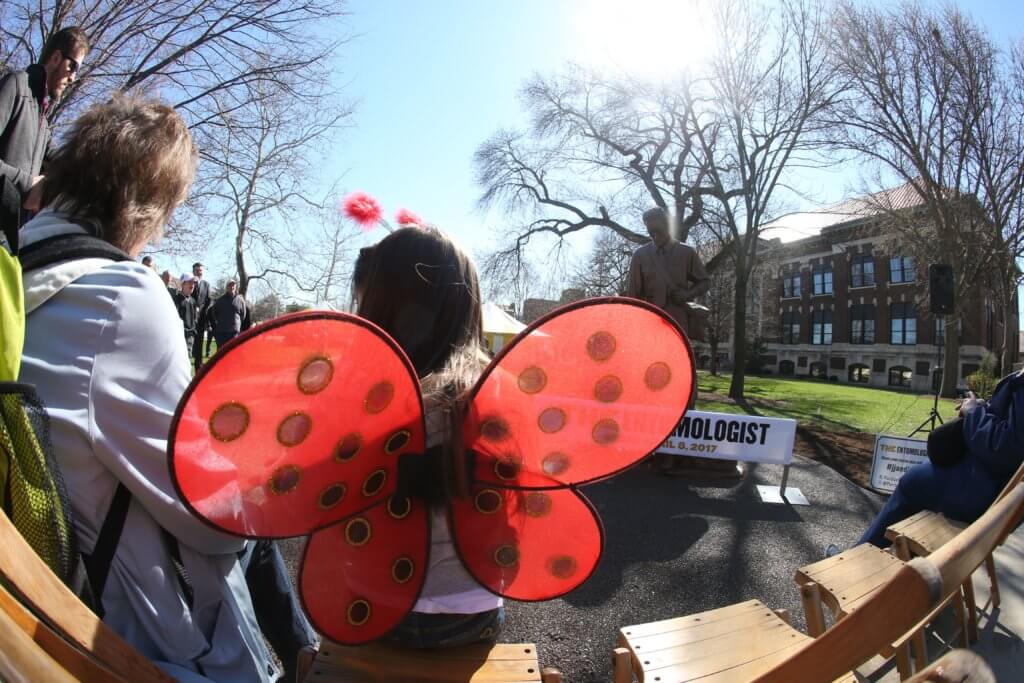

“I think what I’m most proud of regarding Bug Bowl is how we can take creatures people genuinely hate and get them in closer contact with insects, interested in the roles they play in our environment or the way they look. With a little outreach you can get anyone thinking like an entomologist,” he said.

And no activity gets a body up close and personal with insects more than cricket spitting, a central facet of Bug Bowl since 1997. The objective is simple; spit a cricket as far as you can. Like any sport, there are rules. The cricket must be a brown house cricket, have all its limbs intact and weigh a certain amount. Additionally, contestants must stand behind a line to spit and can only hold the insect in their mouth for thirty seconds.

“It’s the same as throwing a shotput or discus,” Turpin described. “Well, not the same, but similar. The key is to have it leave your mouth at a 45 degree angle, too low or high and it won’t go far. Also, you really want to lather them up with saliva. That’s a definite difference from shotput or discus though.”

While Bug Bowl was the first place, as far as Turpin knows, to hold a cricket spitting competition, he’s invented his own mythology for the sport that harkens back to the 1800s and Jean-Henri Fabre, known widely as the father of entomology.

According to Turpin, the story goes that Fabre was extracting crickets by employing a method common at the time, sticking a metal straw into their burrows and blowing them out. One fateful day, however, Fabre’s dog came up behind him and stuck his nose on the exposed skin at the base of his spine, causing Fabre to inhale the cricket, which he was then forced to spit out in shock.

“And so, we got cricket spitting,” Turpin laughed. “It’s all lies of course.”

Pearson said they are already looking ahead to Bug Bowl 2021, planning new activities and ways for the public to interact with insects. "

"We are so sad we won't be able to celebrate our 30th Anniversary year with everyone in person, but know we are contributing to the safety of our community by making the hard decision to cancel Bug Bowl this year. We will move all the plans we had for special 30th anniversary events to 2021. We hope everyone will enjoy some of the surprises we have in store," Pearson said.

Even with this year’s cancelation, there is no question of Bug Bowl’s legacy and the importance of events that encourage the public to interact with nature, even the facets of it that might make them squeamish.

“Bug bowl encourages people to engage with insects and engage in conversations about them,” Stephen Cameron, entomology professor and department head, said. “More broadly than that, it’s a way to safely make contact with them and interact with organisms essential to our planet. People don’t have as much interaction with nature as they once did, but at Bug Bowl and Spring Fest it’s in