Purdue study finds signal cascade that keeps plant stem cells active

Pools of stem cells in the apical meristems of plants are key to continued growth and development. Understanding how these stem cells are maintained and balanced against differentiated cells could lead to methods for increasing crop yield and biomass.

Purdue University scientists have uncovered a key signaling cascade that maintains a balance between those stem cells and differentiated cells. Yun Zhou, an assistant professor in the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology and the Purdue Center for Plant Biology, and Han Han, a postdoctoral researcher in Zhou’s lab, together with other colleagues published their results Thursday (March 5) in the journal Nature Communications.

Undifferentiated stem cells are located in the meristems — the apex or tips of plant shoots and roots. These serve as a bank of undetermined cells that support plant growth and give rise to different organs such as leaves or flowers.

Zhou’s previous work at Purdue showed that the apical-basal gradient of gene expression is essential to keep these stem cells active in the outmost cell layers and their differentiated progeny at internal tissues. Disturbing that gradient leads to severe defects in stem-cell proliferation and differentiation, affecting shoot growth and reproduction. Now, Zhou’s lab has shown how that gradient is initiated and maintained.

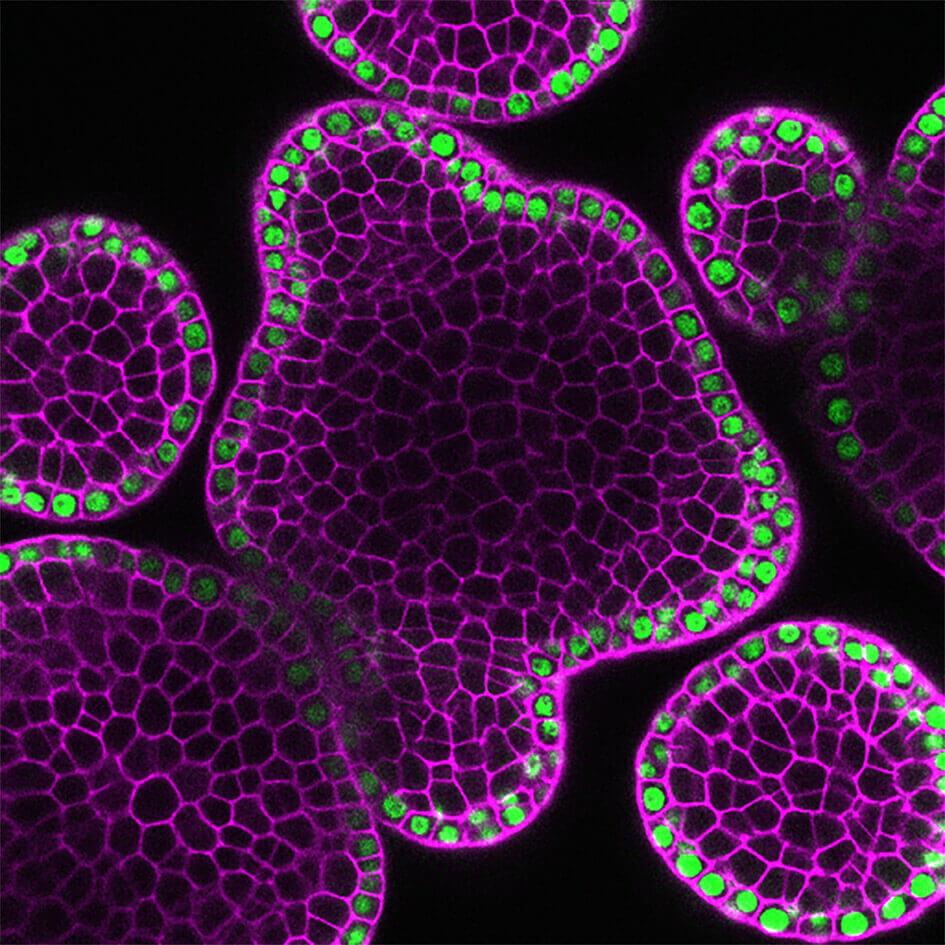

Zhou’s group found that the Arabidopsis thaliana Meristem Layer 1 (ATML1) family of genes directly activates a group of microRNAs in the epidermis of plants. These microRNAs function as a mobile signal that specifically deactivates the Hairy Meristem (HAM) genes. These HAM genes are crucial to maintaining the balance between the stem cells and differentiated cells.

In the epidermis, this group of microRNAs are actively synthesized and the microRNA level is high, eliminating most or all of the HAM genes and maintaining the stem cells. But as the microRNA digs deeper into the interior cell layers, there is less of it to deactivate HAM, keeping HAM concentrated in the basal regions of meristems.

“This is a spatial and temporal regulation leading to the gradient we’ve seen,” Zhou said, “Our results uncover a molecular linkage between the epidermis and shoot stem-cell homeostasis. We find that plant epidermis produces mobile signals to control this gradient and the stem-cell activity. This may open a new avenue for crop improvement in the future.”

The team’s work combines in vivo live imaging, in vitro biochemistry and in silico, or 3D computational, modeling.

Zhou’s lab will continue exploring the basic functions of meristem development and maintenance in an effort to develop methods to control them to increase plant biomass and yield. Purdue University, including the Purdue Center for Plant Biology, funded the research.

One microRNA gene, shown in green, is specifically activated by Arabidopsis thaliana Meristem Layer 1 (ATML1) in the outermost layer of a plant shoot apex. This microRNA determines the concentration gradient of Hairy Meristem (HAM) genes, which controls stem cell function and ensures plants make leaves, flowers and other organs. (Photo courtesy of Yun Zhou)

One microRNA gene, shown in green, is specifically activated by Arabidopsis thaliana Meristem Layer 1 (ATML1) in the outermost layer of a plant shoot apex. This microRNA determines the concentration gradient of Hairy Meristem (HAM) genes, which controls stem cell function and ensures plants make leaves, flowers and other organs. (Photo courtesy of Yun Zhou)