Teacher of Purdue’s first meat science course reflects on lifetime of research

After 75 years, Max Judge still recalls a simple question that set the course for decades of progress in meat science.

Growing up on a farm in Henry County, Judge showed pigs through 4-H. “In 1945, I had the opportunity to host the county pig tour,” Judge recalled. “Lo and behold, leading the tour was Hobe Jones.” Jones taught animal sciences at Purdue for 38 years. “I was excited to tell Hobe that my brother had worked with pigs at Purdue under Cliff Breeden. My brother had told me that Cliff kept his pigs from getting too fat by feeding them by hand instead of on a feeder.”

“I was only 12, but I still remember Hobe’s reply. ‘How are you going to control the amount of feed you need to give them? As they get bigger, they are going to require more and more feed.’”

“It sunk in that there was more to raising pigs then getting them in a pen and brushing them. There is science involved.”

“At that moment I dedicated myself to go to Purdue.” Judge worked with Breeden and studied livestock production.

Upon completion of his bachelor’s degree, Judge served as an officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from 1954 to 1956. Subsequent military assistance allowed Judge to earn his master’s at The Ohio State University. He then returned to Purdue, began instructing classes and earned a doctorate in animal physiology.

“I taught the first meat science course at Purdue and was given the opportunity to develop our program. For that, I will always be grateful,” said Judge. The program focused on the properties of muscle as they relate to the quality of meat.

“We could see things that happened out in the world as a result of our research. When I was on leave in the Netherlands, we had a country-wide effect on the kind of pork they produced.”

Judge found that Dutch farmers were raising stress-susceptible pigs. “If you put them in a strange pen, they would run the fence until they were exhausted.”

Judge’s team found the tendency negatively impacted the formation of muscles used as meat. Pigs of the stress-susceptible genetic strain are no longer raised in the Netherlands.

His team’s research had further applications, including a study of post-mortem changes in pig muscle. “To make a long story short, McDonald’s took our findings and developed the McRib,” explained Judge.

Judge’s list of colleagues extended beyond animal sciences including Purdue’s current provost and executive vice president for academic affairs and diversity.

“Jay Akridge was a young assistant professor in agricultural economics. Jay was a member of our research team funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for studies on pork quality. The secretary of agriculture referred to us as the ‘Lean Team,’” noted Judge.

“We can’t take all the credit for the improvement in the muscularity and meat quality of hogs coming to the market, but there has been a vast improvement that is obvious to people of my age group.”

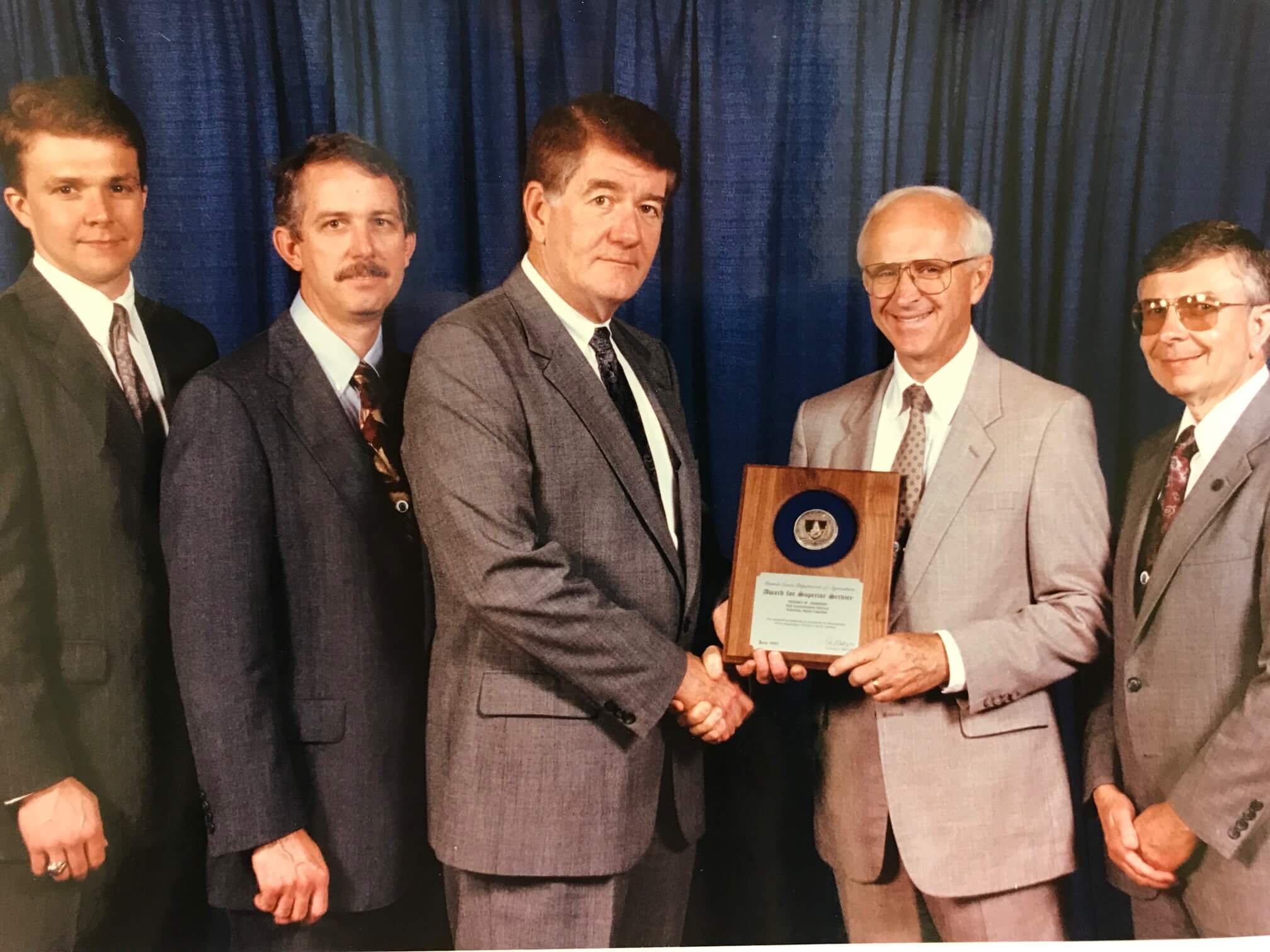

Judge was the interim head of Purdue’s Department of Animal Sciences for portions of 1985 and 1986. He also served as the major professor to 30 advanced degree students. After retirement, Judge was honored with a lifetime career award as an Animal Sciences Distinguished Alumnus.

Ross Jabaay, a fellow Animal Sciences Distinguished Alumni and former graduate student of Judge, led a 2018 fundraiser that recognized Judge with a named space in Purdue’s Land O’ Lakes, Inc. Center for Experiential Learning, the Max Judge Classroom Devoted to Meat Science and Muscle Biology. The honor indirectly led to Judge originating the Student Outreach to Consumers project. Through his support, students have the opportunity to travel to scientific meetings.

“I will love Purdue until my dying day, and not just because of the meat science program. Purdue gave me so many opportunities and was a great place to work.”