Alumnus adapts restaurant to protect the health of his business and patrons

B

efore electricity and modern refrigeration, icehouses were built to keep ice and snow frozen, and it was sold and shipped year-round. As refrigerators grew in popularity, icehouses shifted their business model. They became the predecessor to convenience stores, selling perishable groceries and cold drinks. 7-Eleven traces its origin to one such icehouse.

Other icehouses, particularly in Texas, became eateries and bars where the community gathered. These inspired the concept and name of Purdue Agriculture alumnus Lee Stanish’s restaurant, Eddie Joe’s Icehouse.

Like icehouses of the past, Stanish realized Eddie Joe’s Icehouse had to adapt in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Stanish earned a bachelor’s in agricultural economics from Purdue in 2003. Three years later, he joined the university, serving as an international 4-H programs coordinator while earning a master’s in agricultural education. Stanish then served as an agricultural economics project manager for four years.

“In 2015, I had the opportunity to start my own restaurant,” recalled Stanish. “I knew I would always regret it if I didn’t give it a try.”

Stanish opened Eddie Joe’s Icehouse in West Point, a town with 600 residents, hoping to become “Greater Lafayette’s BBQ and Tex-Mex destination

“When the pandemic hit, we had to think fast. I don’t think anyone was sure of the right thing to do, but we had to try something.”

Stanish rushed to shift the restaurant’s focus to take-out, which had historically been 7% of their orders.

“Increasing our take-out orders to five times what they had been was like drinking out of a fire hose. We had to restructure our entire kitchen and our front-of-house staff.”

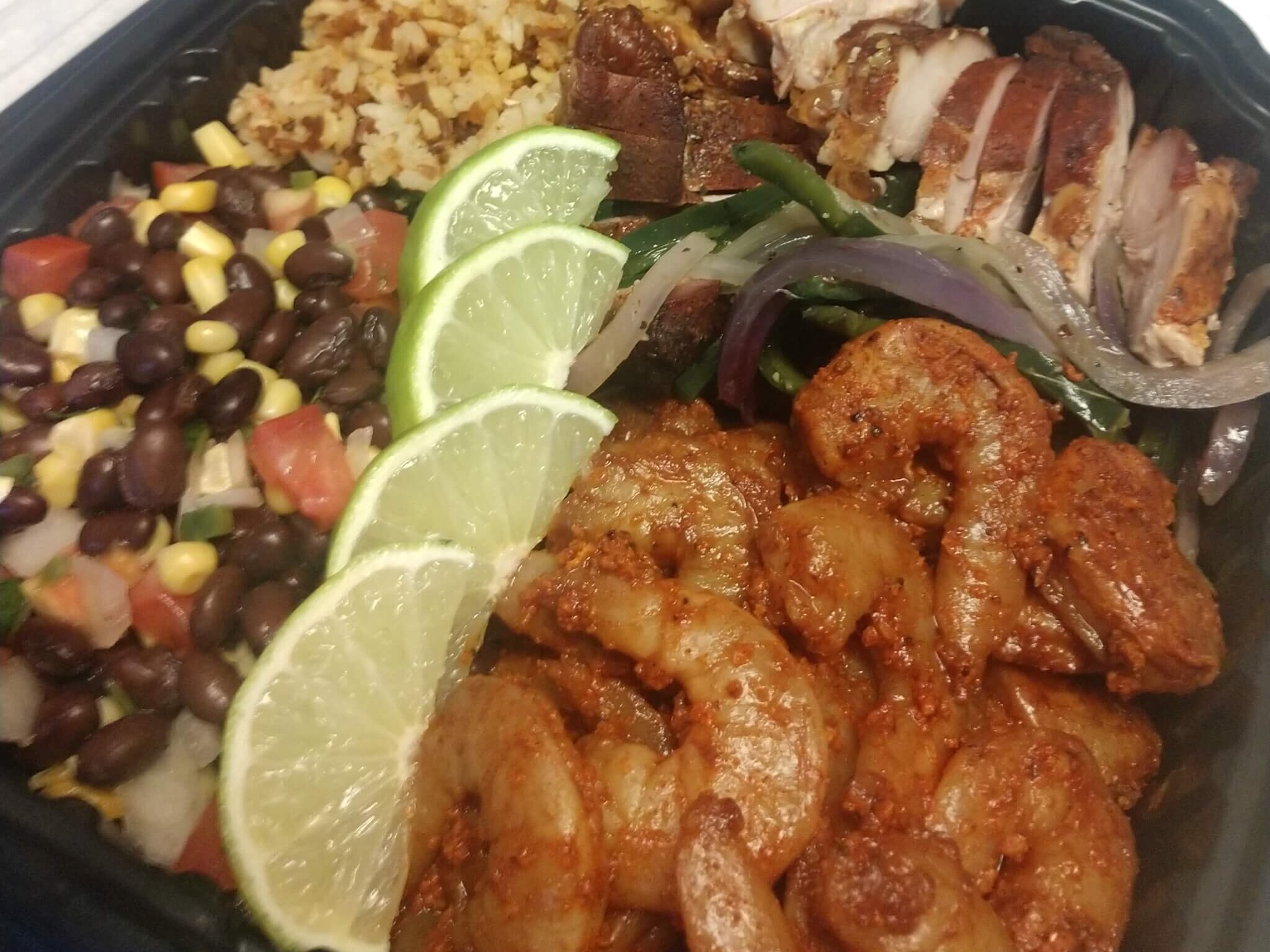

Stanish realized he also needed to adjust the restaurant’s menu. “We had to rethink our packaging and consider what food travels well. We couldn’t put something like onion rings in a box and hope they would still be up to our standards 15 minutes later.”

Stanish created Icehouse Boxes, meals designed specifically for carry-out. The wide variety of offerings ranged from fully-prepared meals, to kits which could be assembled at home. The staff even offered theme meals for holidays such as Easter, Cinco de Mayo, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day and the Fourth of July.

Through his struggles, Stanish realized the importance of giving back to the community. When supplies were scarce, he gave away milk and toilet paper with his customers’ orders. At the end of the school year, he handed out free cinnamon rolls to students during West Point’s Parade of Graduates.

In June, Stanish gave his staff nearly 100 meals to pass along to others. “The criteria was simply to give them to someone who’s had a rough time, hopefully brightening their day.”

Stanish also used the shutdown as an opportunity to support local businesses with new partnerships, buying ground beef from nearby Hodgen Farms for smoked meatloaf boxes to be sold at People’s Brewing Company.

Once businesses began re-opening, Stanish saw orders begin to drop back down. “We’re in a weird spot now,” said Stanish. With restrictions lifting, restaurants have begun to re-open, but physical distancing prevents Eddie Joe’s Icehouse from approaching its previous limit of 100 customers. “If you operate any business at half capacity, it’s not healthy for the company,” explained Stanish.

“My gut tells me this is going to last for a while. Most restaurants will need to start becoming food businesses in a broader sense to remain successful. They are going to have to look at how the market changed.”

In response, Stanish sped up his long-term plans to diversify the restaurant’s portfolio. “When you’re in a small town like we are, distribution is a key issue. We’ve always wanted to have a food truck. We’ve made the purchase and are getting one ready to go.”

“As I look back, I’m glad we made the decisions we did. We’re staying hopeful. Things won’t just go back to the way things were, that time has passed. We’re going to continue doing what we can to adapt and help.”