Ag labs rise to COVID challenge

Last fall in Plant Structure & Tissue Biology, Mia Brann and her classmates called over teaching assistants and their instructor to help determine if they had correctly focused on the plant cells they had just loaded into their microscopes. The 22 students pulled their faces from the scopes as TAs stepped in and pressed their eyes to the lenses to offer guidance.

It’s a scene that had been routine in Purdue lab classes for years, even decades, but that now violates the rules meant to keep students, faculty and staff safe from the virus causing the COVID-19 pandemic. Large gatherings and shared equipment expose the campus community to risk of contracting and spreading the virus.

That risk hasn’t stopped or even slowed most botany labs. Instead, teachers and students alike are finding ways to transform the lab experience and, often, enhance it.

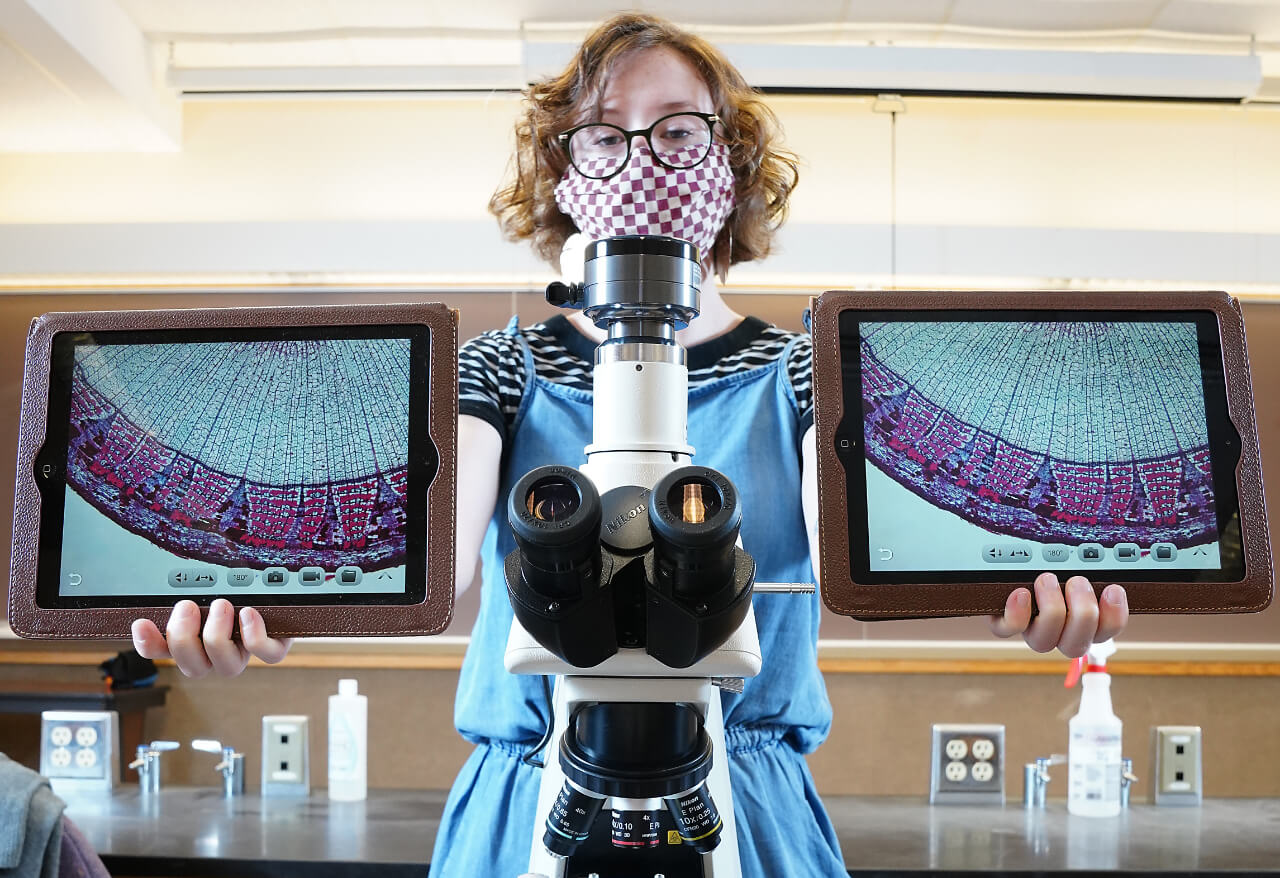

Brann, a junior botany major, is now the TA who surfs the room to help a new batch of students. Rather than 18 at a time, labs are now broken into three groups of six students across three rooms. And instead of pressing her face to students’ microscopes, new Wi-Fi-enabled microscopes allow her to look at her phone to see the images cast to it from the devices. There is no contact with the students, their phones or their microscopes. The microscopes create a hotspot, and students can connect to it to pull high-resolution images from the scopes to an app on their mobile devices.

“If the students need help finding something on their slides, I can quickly and easily pull up their images on my phone and tell them where to move and focus,” Brann said.

Students can also capture photos of the images on their screens. That’s a huge step up from how students have taken photos for years — using cellphones to snap pictures through the eye pieces of their own microscopes.

“Students turn in these photos as assignments and use them to study,” said Yun Zhou, an assistant professor of botany and plant pathology who teaches the course in which Brann assists. “With this technology, we know the students are seeing exactly what they’re supposed to and are getting better aids to help them learn the information. It’s a better learning experience for them.”

The microscopes have also solved another challenge instructors have had for years. John Cavaletto, botany and plant pathology teaching lab coordinator, said this semester a student with a visual disability can now pull the microscope images up on a tablet screen and participate more fully in the class.

“In the past, I would have had to come up with some really crude ways to work with him, like taking photos through the lenses and printing out static images for him,” Cavaletto said. “Now, he can do the lab just like his peers because we can accommodate his visual impairment.”

COURSE ENHANCEMENTS

Students in agricultural and biological engineering’s biotechnology laboratory course start their semesters on a treasure hunt, collecting samples of soil teeming with microscopic life. In particular, they want to isolate and identify a never-before-seen bacteriophage, a virus that infects bacteria and can be useful in research and drug discovery.

The students usually spend most of their time in labs, isolating and purifying the viruses which will then have their genomes sequenced. Later, those genomes are annotated and entered into a Howard Hughes Medical Institute database that is available to researchers around the world.

find and identify novel bacteriophages from soil.

The lab has been redesigned this year to give

students who cannot spend as much time

in labs more information about how their

work can be used and careers in biotechnology.

Normally, labs would be busy with undergraduates on the hunt for their phages, but COVID has cut the number of lab hours available to those students. Kari Clase, director of the Biotechnology Innovation and Regulatory Science Center and an agricultural and biological engineering professor, turned to her graduate students Emily Kerstiens and Gillian Smith for ideas.

“Most semesters, students are in the lab 10 to 20 times trying to isolate a novel phage. That’s not possible now,” Clase said. “We worked with past students to determine what they liked and what they got the most from in the course so we could try to keep those elements. Then Emily and Gillian found ways to get the lab work done under our new constraints and enhance the course.

Kerstiens and Smith first leaned on more “peer leaders,” previous class students interested in gaining a more advanced understanding of phages. In years past, there would be just a few of these students shadowing Clase and graduate students, mixing media and prepping labs for work.

Now, around a dozen of those peer leaders are getting in the labs to advance work. While students often do multiple rounds of sample dilutions to isolate a phage, now the peer leaders do several of the later rounds. Current students get the experience, and the peer leaders get more hands-on time.

“We had to basically accommodate for students not being able to come into the lab physically,” Smith said. “Now our peer leaders, who are interested in getting more experience, can take a more active role in the research.”

With less time for students in labs, Kerstiens and Smith developed learning modules to give students more in-depth knowledge about the work they’re doing. Students watch recorded lectures, Netflix and YouTube videos, listen to podcasts and read relevant scientific journal articles to learn more about how biotechnology is used and ways they might apply the knowledge in their future careers.

“This is material they can consume at their own pace and that gives more in-depth knowledge about the work they’re doing,” Kerstiens said. “A lot of this content will probably stay with this course even after we’re able to get back into the labs more regularly.”

CRIME SCENES

Entomology’s forensic investigations lab, the scene of one of the most popular minors at Purdue, is regularly full. This fall, with 165 students, is no exception.

Normally, Trevor Stamper would divide those students into groups of 24, but COVID limits labs to 12 students. That makes holding more than just a few in-person sessions impossible. Instead, Stamper is sending the murder mysteries home with his students.

“We don’t have the manpower to run double the number of sessions per week.,” said Stamper, forensic sciences program director in the Department of Entomology. “This is an extremely hands-on class, and we set up fake crime scenes and have students gather around. Since we can’t do that, we developed take-home kits that allow students to set up their own scenes and document the work they’re doing.”

The kits contain items such as powder to dust for fingerprints and non-caustic chemicals that can be used for simple tests. Stamper pairs those kits with a series of pre-recorded lectures that students can consume at their own pace. He and students also check in via videoconference regularly to get live instruction, hold group discussions and ask questions. Students make up their own crime scenes, analyze blood spatters and take diligent notes on the evidence they find.

“They’ll have a ‘dead body’ in the scene, and it will often be mom or dad who’s laying there with their tongue out. They can be more creative with their environment rather than just having us stage it for them,” Stamper said. “I’ve found that some of this can be done remotely surprisingly easily.”

The videos are also helpful, Stamper said, because lectures on a topic often occur well before the lab work. Having the lectures recorded allows students to watch them just prior to the hands-on work or re-watch them to brush up on the material.

“That not only allows us to overcome that lecture-lab alignment problem, but gives students time to master the information at their own pace,” Stamper said. “They’re more active when we virtually meet. It’s something I think has had a lot of positives.”

MOVING FORWARD

The pandemic has challenged the Purdue community to reconsider how it handles labs and will likely create a few new normals.

Clase expects many of the changes to her labs to remain, and Stamper believes recorded lectures can be updated and useful for many of his students.

Zhou said his lab is only seeing the tip of the iceberg with the Wi-Fi-enabled microscopes. He hasn’t even attempted to use the time-lapse and video functionality yet but plans to in the coming semesters.

Crises require adaptation. The College of Agriculture’s labs have not only adapted, they are thriving.