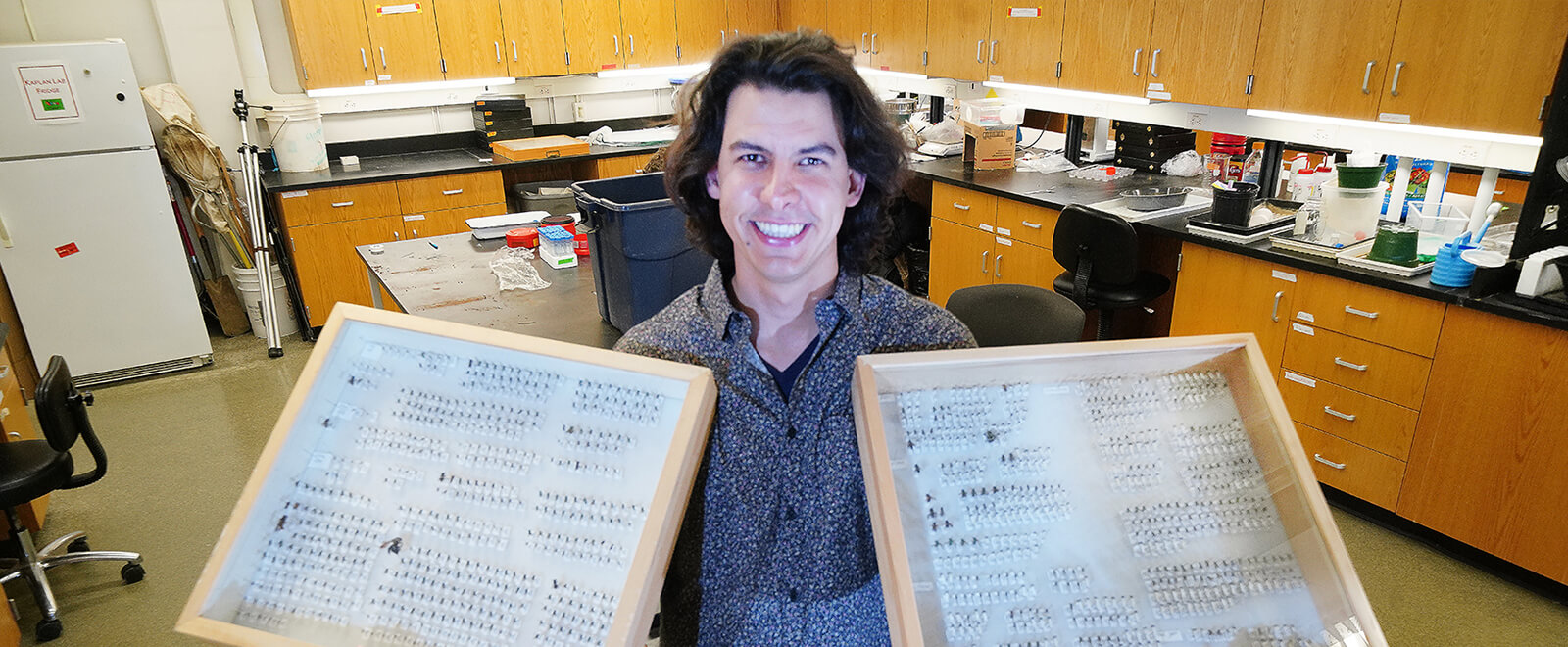

Student’s research helps watermelon growers find sweet success

"E

ven though some days I’m getting out of bed to reach the field before the flowers open, it’s easy for me to find the endpoint of who we’re doing this for,” said Jacob Pecenka, a Ph.D. student in entomology. “Watermelon growers in Indiana.”

Pecenka grew up in South Dakota where fishing and nature walks sparked his interest in biology. At South Dakota State University (SDSU), he earned a bachelor’s degree in biology and biotechnology. A summer job with a USDA scientist served as his introduction to entomology.

“Looking at insects as working with us and not against us was something I instantly clicked with,” Pecenka recalled. “It wasn’t particularly exciting work – sweep netting and counting bugs on soybean leaves. But I saw the application in this world of research, a world I’d never been aware of.”

Pecenka stayed at SDSU for a master’s degree, studying the effect cattle grazing management made on dung beetles. In 2017, Pecenka began a doctoral program at Purdue under the guidance of Ian Kaplan, a professor of entomology.

In his multi-year project, Pecenka evaluated how an integrated pest management approach to growing watermelons in Indiana affected the ability of bees to provide pollination. Indiana’s watermelon production ranks fifth in the United States.

“My work now is more popular with my wife,” said Pecenka, noting that he brings home honey and watermelons instead of the manure-encrusted shoes of his past.

Using plots at Purdue Agricultural Centers (PACs) statewide, Pecenka compared the effect of regular spraying versus scouting for striped cucumber beetles and spraying only when the number of pests per plant exceeded five, a threshold that lowers yield.

His research showed the scouted plots had more beetles – but also more pollination and higher yields.

“In three years of scouting the beetles, we only had to spray four times out of 300 total events. On the flip side, pollination visits were 130% higher when sprays weren’t out there.

“We’re showing that growers are putting out way more insecticide than they need to. They are spending more money and possibly doing some unintended damage.”

After completing his degree in the coming year, Pecenka wants to stay in applied research, answering pressing questions for growers at a university or government agency.