From health conscious to earth conscious: how chia seeds could become a single use plastic solution

Beyond spreading the seeds across a ceramic novelty head to create a funky, green-growing hair style, researchers in Purdue’s Department of Food Science have found chia seeds could be a potential solution to single use plastic pollution.

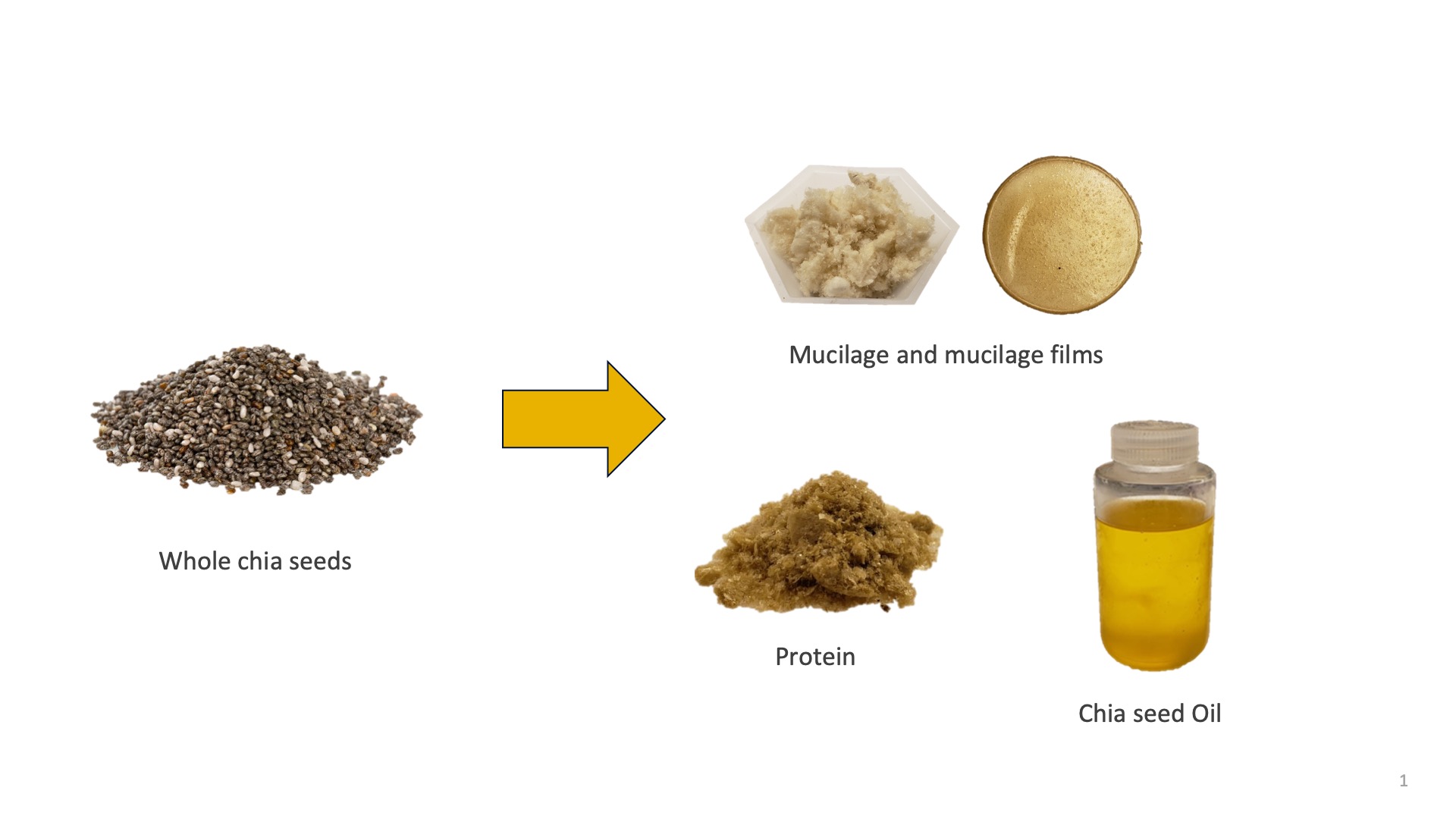

Andrea Liceaga, associate professor of food science and director of the sensory evaluation laboratory, said her previous research focused on finding nutritional benefits behind the protein rich seeds, requiring them to be separated from the mucilage, or thick gel-like substance that coats the chia seed and creates a gooey coating when the seed is hydrated.

Photo by Tom Campbell

Photo by Tom Campbell “The mucilage is a natural carbohydrate and byproduct of the seeds, so we began wondering what could be done with it,” Liceaga said. “We had heard from research in medical journals that chia seeds were becoming trendy among consumers because of their health benefits, but there were reports of people eating larger quantities of them. The seeds would then swell up inside of them and create blockage.”

When separating the mucilage from chia seeds, Liceaga said she and her team of graduate students found the dehydrated mucilage looked similar to cotton candy, leading them to wonder what else could be done with the byproduct that would end up being thrown away.

Why not try to create a replacement for plastic, knowing single use plastic is the largest contributor to environmental pollution?

“We tested the chia samples for flexibility and durability, which had great potential for both,” Liceaga said. “Right now, we are working with simple films that are created in petri dishes.”

The samples Liceaga’s team have created are foldable and resemble that of everyday plastic packaging.

The next step from films in petri dishes would be to create a plastic analog, such as a fork or a serving cup, Liceaga said. That will require further funding. Another plastic source she is interested in recreating with the chia byproduct would be 3-D printer ink as it continues to become a growing field, leading to high potential for further plastic waste pollution.

Strength, elongation, flexibility, and light transmission are all boxes that need to be ticked off when comparing the chia seed product with traditional plastic. Decomposition is one check box Liceaga said she is most interested in.

“The consequences of plastic are always there,” she said. “We are comparing something that takes 500 years to decompose to something that could decompose in a mere few weeks, potentially a year.”

The next steps for the chia-based plastic to be brought to commercialization are slowly happening as patents for the technology and concept have been submitted. However, as Liceaga notes, additional funding for research will be critical to move the project from discovery to product.

Photo by Tom Campbell

Photo by Tom Campbell Additional assets for media use are available here.