Purdue startup is pushing the envelope on research-grade data

The catchphrase on GRYFN vehicles, “Drones powered by Boilers,” is meant to be whimsical, reflecting that all employees of the 2018 startup have a Purdue degree. “It’s kind of fun,” says CEO Matt Bechdol. “I’m not aware of true boiler-powered drones — but ours sure are.”

Despite its tongue-in-cheek motto, GRYFN offers a serious study of the potential long-term impact of ideas that move from the College of Agriculture into commercial markets.

Eight Purdue faculty members in varied agriculture and engineering disciplines collaborated on the research behind GRYFN. A 2017 U.S. Department of Energy grant funded their work on remote-sensing hardware and software for field-scale plant breeding and agricultural research. The technology is also applicable in forestry, natural resources and environmental studies.

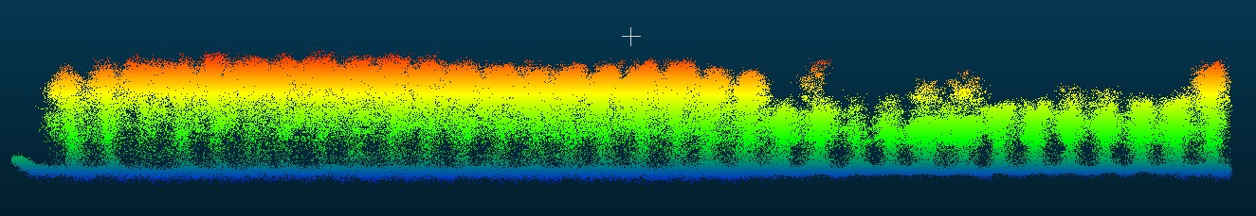

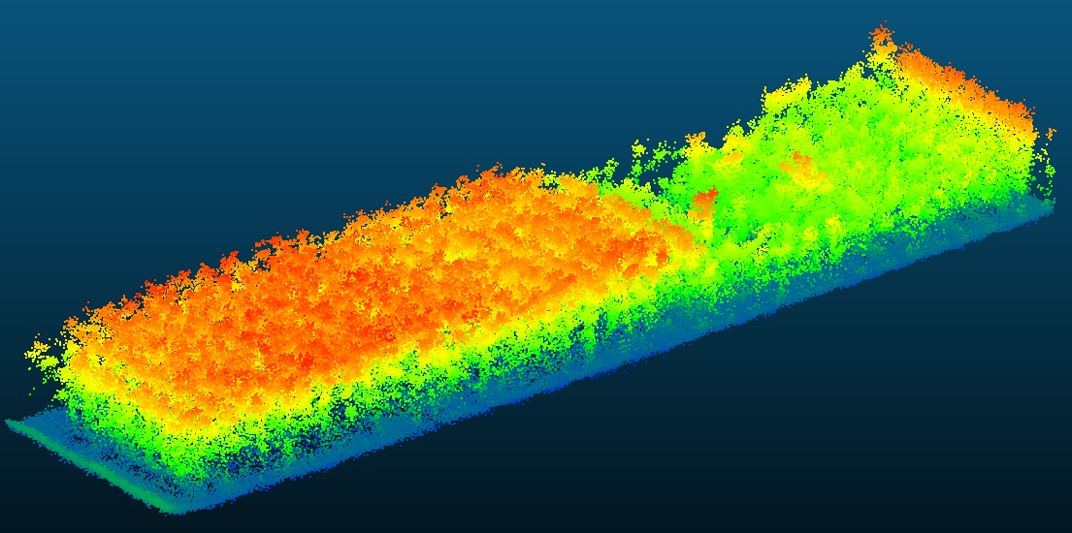

Their efforts led to an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) platform that carries different imaging sensors, including visible RGB, LiDAR and hyperspectral, and thermal. “Our core solution takes multiple research-grade sensors — in this case, on a drone — and co-aligns them in a precise way to enable research,” Bechdol says. “Which essentially means we’re in the business of providing high-quality data and closing the gap between acquisition and analysis so that researchers go to the next step.”

Flying multiple sensors simultaneously saves time and ensures consistent conditions. GRYFN’s software processes the data together into an accurate, co-aligned “data-cube” that gives plant breeders in major commodity crops analytic solutions for high-throughput phenotyping in the field.

The technology was incubated in the Purdue Foundry and licensed through the Purdue Research Foundation Office of Technology Commercialization. In spring 2021, GRYFN won $100,000 from Purdue’s agricultural innovation fund, Ag-Celerator.™ The funds empowered developers to enhance the software that not only supports custom analytics for GRYFN customers, but also allows customers to embed their own scripting analytics directly into GRYFN workflows.

“Working collectively on the grant with Purdue gave us a unique opportunity to focus on industry pain points,” Bechdol says. “It gave us a bit of latitude and patience that most startups don’t get, which means our customers get a much better product.”

A tool for scientists

One of GRYFN’s early customers was Yang Yang, director of digital phenomics at Purdue. “We are a very good example of where GRYFN thrives in terms of providing sensing capabilities to enable research in agriculture,” Yang says. “We are able to use this platform to benefit a wide array of our principal investigators.”

Not only does GRYFN provide more information in every single flying event, Yang says, but it has another unique advantage: It eliminates the need to establish ground control points, or GCPs — ground markers that match locations on an image with real-world coordinates. The bigger the project, the more complex the GCP. GRYFN does away with the logistical problem of deploying hundreds of markers over large fields where, for example, tillage research occurs.

Yang cites two faculty members leveraging GRYFN data. Mitch Tuinstra, professor of plant breeding and genetics and Wickersham Chair of Excellence in Agricultural Research, and his students use LiDAR images to estimate height of corn plants — a measurement traditionally done manually with a stick. The new technology provides fast, large-volume measurements across a field multiple times per season. “The height of corn is closely correlated to the yield estimate, so that’s very good data,” Yang says. Plant breeders can further use hyperspectral data to understand the plants’ water and nutrient status.

The technology also collects data for corn and soybean disease assessment by Darcy Telenko, assistant professor of botany and plant pathology. “Dr. Telenko and her student are leveraging the data acquired by the GRYFN platform to see if we can detect and quantify disease in row crops before visualization,” Yang says. “In other words, we want to set up an alarm even before farmers, even experienced ones, can detect there’s disease in the field.”

LiDAR uses laser pulses to measure physical and structural elements of trials such as plant height, canopy penetration and more. (Photo courtesy of GRYFN)

LiDAR uses laser pulses to measure physical and structural elements of trials such as plant height, canopy penetration and more. (Photo courtesy of GRYFN) Putting phenomics to work

The grant that funded development of GRYFN’s product ended in May. “We’ve only been selling for about 14 months, but our customers are excited about working with us because they value that we think like they do, and we deliver custom integrations for current objectives

while providing agility for future ones,” Bechdol says. “Our Purdue history and culture are critically important for that.” Ag Alumni Seed is both an investor and a customer, says its CEO, Jay Hulbert. The Romney, Indiana-based supplier of high-quality popcorn hybrids has also supported Purdue’s Indiana Corn and Soybean Innovation Center and Ag Alumni Seed Phenotyping Facility. “We’ve learned about phenomics from working at Purdue,” Hulbert says. “We’ve learned about the potential of remote imaging, and we decided that rather than leaving it as an academic issue, we would see if we could work to implement it in our business.”

Because the popcorn market is non-GMO, the small specialty seed company has relied on traditional plant breeding. “We have begun to try to augment our traditional plant breeding with advanced technologies that allow us to stay non-GMO,” Hulbert explains. “That includes using genomics.”

He hopes GRYFN-produced data will enable Ag Alumni Seed’s four popcorn breeders based in North America and South America to communicate quantitatively about characteristics of popcorn that previously were evaluated on a qualitative basis.

It’s still early in the process, he acknowledges. “I don’t know of any other platform that incorporates that number of sensors on one bird, which gives us a ton of data,” Hulbert says. “Now the trick is turning that data into actionable information and incorporating it into our plant breeding system so that’s its usable by multiple breeders in different parts of the world. That’s way easier said than done.

“We’re a small company,” Hulbert adds. “We don’t have a team of data scientists that can just plug this in to a system like one of the really big seed companies could. But we’re getting there, and the folks at GRYFN are helping us.”

LiDAR uses laser pulses to measure physical and structural elements of trials such as plant height, canopy penetration and more. (Photo courtesy of GRYFN)

LiDAR uses laser pulses to measure physical and structural elements of trials such as plant height, canopy penetration and more. (Photo courtesy of GRYFN) Broader possibilities

To maximize this Purdue intellectual property, GRYFN’s leadership is looking beyond its initial applications. “Agriculture is important, and our focus on plant science and phenomics is hugely important in terms of our go-to-market strategy,” Bechdol says. “But we were always thinking about pivoting from pure agriculture. We have positioned ourselves as a premium research-oriented company. For us it’s not a strategy pivot, but telling a different story.”

By streamlining the difficult process of high-quality, co-aligned multisensor data, GRYFN workflows appeal to researchers in such fields as forestry, oceanography, and environmental remediation, to name a few. The company has received inquiries from prospective clients that might want to use the technology in surveying, or to measure methane leaking or climate impacts.

In addition to Bechdol, two Purdue graduates work for the company: Evan Flatt as director of solutions and Ryan Riley as UAS pilot and data analyst, as well as a fulltime intern. And while Bechdol knows that growth will require hires from beyond the university — “We’re going to have to search for talent hard, far and wide because there’s great competition for it,” he says — he expects Purdue connections to remain strong.

“We’ve hired good Purdue people that are creative problem solvers but also are playing chess with this,” he says. “They’re trying to think three, four moves ahead of what our users are going to be doing that we need to include in our hardware now, so that that transition is easier for them, which means change is faster, easier, and cheaper — which means they get a better value.

“And if we can do that, we’re going to get repeat customers.”