Experiments identify important new role of chemical compounds in plant development

Genetic manipulations of lignin research yield surprise finding

Researchers who manipulate lignin, a molecular fiber that allows plants to grow tall and transport water, unexpectedly discovered its synthesis has more far-reaching effects on plant development than previously suspected.

“My lab has had a long interest in studying the extent to which we can modify plants, specifically the lignin biosynthetic pathway,” said Clint Chapple, Distinguished Professor of Biochemistry at Purdue University. “Of all of the components that make up the plant body, lignin is the one that’s easiest to manipulate. And it has an impact. The pulp and paper process is really about removing lignin.”

Lignin also affects the quality of animal feedstocks and of plant biomass to produce biofuels. “We’ve had some significant success with it over the years. But we ran into a set of observations that we couldn’t explain,” Chapple said.

Chapple’s team genetically engineered the flow of chemical precursors that feed the pathway leading to lignin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana, a widely used experimental plant species.

“When we took two strategies that worked quite well on their own and combined them, instead of getting a synergistic effect, we got plants that were only a few inches tall. And we were really puzzled by that,” Chapple recalled.

Researchers proposed four main ideas to explain this phenomenon. “There was a lot of uncertainty over which one, or ones, were correct,” said Fabiola Muro-Villanueva, who earned her PhD in biochemistry at Purdue in 2020.

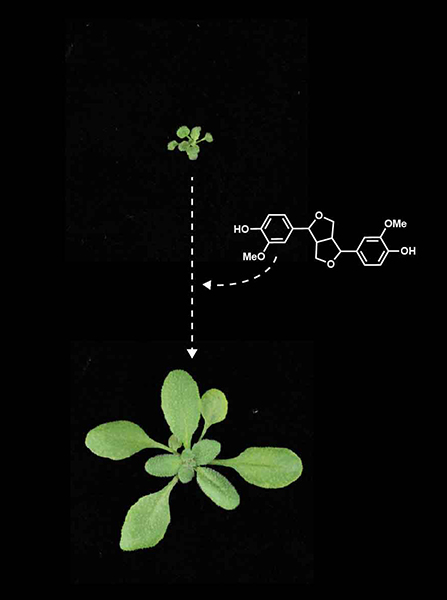

To learn more, Muro-Villanueva spent several years conducting laborious experiments, testing the effect of various plant-derived chemicals on thousands of plants. In the end, she found a way to restore growth to the plants by providing a compound called pinoresinol. Muro-Villanueva, Chapple and nine co-authors from Purdue and elsewhere published their findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Purdue researchers have found that they can rescue the growth deficit of Arabidopsis thaliana plants with altered lignin composition by adding pinoresinol. (Photo provided by Fabiola Muro-Villanueva)

Purdue researchers have found that they can rescue the growth deficit of Arabidopsis thaliana plants with altered lignin composition by adding pinoresinol. (Photo provided by Fabiola Muro-Villanueva)  Arabidopsis thaliana plants, some of which are normal and others that are exhibiting dwarfism. (Photo provided by Fabiola Muro-Villanueva)

Arabidopsis thaliana plants, some of which are normal and others that are exhibiting dwarfism. (Photo provided by Fabiola Muro-Villanueva) “It seems to be a hormone-like growth compound,” said Muro-Villanueva, now a postdoctoral fellow in molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University.

In the work’s early stages, Muro-Villanueva observed changes in the plants’ production of lateral roots, the branches that make up the root system. And they had changes in the production of root hairs, which are important for water absorption.

“Those are aspects of plant development that don’t really have very much to do with lignin,” Chapple said.

The researchers added back to the plants a compound called coniferyl alcohol, a key precursor compound to lignin formation. This resulted in root hairs that grew big and normal instead of short and deformed-looking.

“That was really very unexpected,” Chapple noted. “It seems that there’s some function for these compounds in plants that we hadn’t appreciated before.”

Until now, plant scientists had widely assumed that pinoresinol serves only as a lignin building block. “Our evidence shows that it’s more than just replacing a building block in lignin. We don’t know the mechanism, but we think there is a much bigger story here,” Muro-Villanueva said.

The findings add new insights to the long list of plant capabilities.

“Plants are excellent chemists. They make a wide variety of compounds that are intrinsically interesting,” Chapple said. Collectively, they make hundreds of thousands of compounds, although individually they often specialize in specific compounds we associate with particular plants.

“They perform many functions. They allow the plant to resist ultraviolet light. So basically, plants make their own sunscreen,” he said. They also deter insect and bacterial attack. And from a human perspective, some of these compounds give our food flavor or aroma, while others provide medicinal properties.

“This is basic research,” Chapple said. “But if we are to move biofuels forward with manipulation of plants to optimize those processes, it’s important that we have a thorough understanding of the roles these pathways and chemicals have in plant development.”

Otherwise, he fears that researchers could put a newly developed variety into the field only to see it fail to perform as expected because they lack a critical understanding of what they can and cannot do with critical biosynthesis pathways.

“We need to have a better understanding of how plants perceive and respond to these compounds,” Chapple said. “And how does their absence lead to these dwarfing effects and alterations in root development?”

This study was supported by the Direct Catalytic Conversion of Biomass to Biofuels (C3Bio), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.