NAECC and Student Farm continue a thousand year-long agricultural tradition

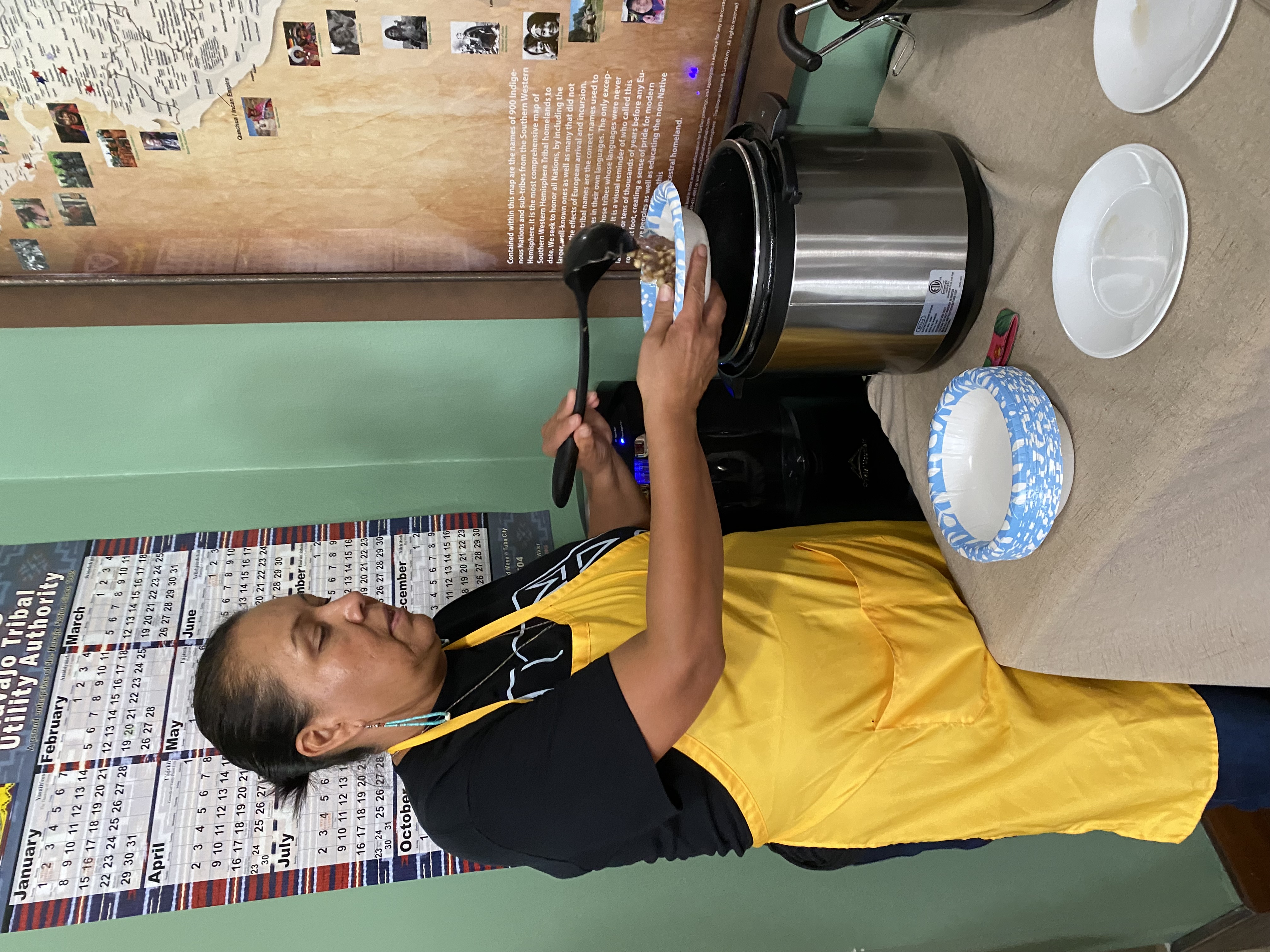

A table full of savory soups, hearty vegetables and sweet fry bread served as proof that even hungry squirrels couldn’t stop the Purdue Native American Educational and Cultural Center (NAECC) from celebrating their annual Three Sisters Dinner, coinciding with the week of Indigenous People’s Day.

“The squirrels got the food this year,” laughed NAECC director Felica Ahasteen-Bryant, a member of the Navajo Nation, who had helped clean up the garden outside of the NAECC the day before. “None of the dishes here are from our garden, but it was a good learning experience. We teach people how to grow the Three Sisters to teach about Indigenous people.”

“The squirrels got the food this year,” laughed NAECC director Felica Ahasteen-Bryant, a member of the Navajo Nation, who had helped clean up the garden outside of the NAECC the day before. “None of the dishes here are from our garden, but it was a good learning experience. We teach people how to grow the Three Sisters to teach about Indigenous people.”

The Three Sisters, corn, beans and squash, were traditionally grown together by many indigenous groups to supplement foraging for other foods and referred to as “sisters” because of the symbiotic relationship between the three plants. While the corn grows tall, beans crawl up the stalks, and squash is planted around the mound so that it wraps around the corn and beans as it grows. The squash’s prickly, thorny vines are good protection from unwanted animals. Nutritionally, the Three Sisters also offer complete protein.

According to Buster Landin, a member of the Anishinaabe and Tlingit Nations and graduate assistant at the NAECC, corn was originally cultivated in Mexico but spread over time, eventually making its way to the Midwest region.

“People imparting their will on plants and practicing agriculture have been around for nearly 10,000 years, supplementing hunting, gathering and fishing,” said Landin, who is also a PhD student in archaeology and anthropology. “This type of small-scale agriculture is what I’d call, ‘plant it and forget it.’ It doesn’t require a lot of upkeep, and small family plots like the one outside the NAECC were popular among Indigenous people.”

The Three Sisters Garden was started in 2021 when the NAECC partnered with a local Myaamia elder, who gifted the center seeds. In 2022, the NAECC collaborated with the Purdue Student Farm, managed by Chris Adair, to grow the garden. While the Student Farm, a small, sustainable farm managed by the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, provided guidance and support, the NAECC used seeds from tribal nation seed banks, intentionally connecting culture with agriculture.

Along with beans, corn and squash soup to celebrate the harvest was neeshjizhii, a traditional Navajo soup made of dried steam corn and beef. Fry bread to dip and sauteed squash and onions served as fragrant sides.

Along with beans, corn and squash soup to celebrate the harvest was neeshjizhii, a traditional Navajo soup made of dried steam corn and beef. Fry bread to dip and sauteed squash and onions served as fragrant sides.

“Fry bread is not super traditional in the way that it was here after contact with Europeans, but since tribal nations didn’t have permanent structures to cook with like ovens and stoves, it was a way to cook with flour and still have a mobile society,” said Felica. “Moving from season to season and place to place, that’s how you make sure you’re not impacting an environment too much at one time.”

The slightly sweet bread is made from a simple mixture of flour, baking soda and water. While sizzling sounds emanated from the porch, Navajo students kneaded dough by hand before frying.

“Different cultures make the bread in different ways, and there are many variations,” said Felica. “We decided to incorporate dishes from several traditions, like both Navajo and Anishinaabe, because our students represent many tribal nations.”

After students, staff and faculty from all corners of campus gathered in the dining room to enjoy the feast, Ramona Dwyer, a member of the Anishinaabe Nation and Forestry and Natural Resources master’s student, reflected on what the dinner meant to her.

"Indigenous People's Day is a step in the right direction, but it can be used as a checkbox by institutions to showcase diversity without more tangible support for marginalized people. As Anishinaabe, we would have celebrated with a feast like this every season. To me, this feast is less about Indigenous People’s Day and more about the Indigenous community at Purdue coming together and welcoming the greater Purdue community."

The Purdue Student Farm, a small sustainable farm managed by the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture (HLA), is located on campus near the Kampen Golf Course and Daniel Turf Center off Cherry Lane.