Paper-based biosensor offers fast, easy detection of fecal contamination on produce farms

Purdue team demonstrates portable system for first time in the field

Purdue University researchers are introducing a new biosensor technology to the agricultural industry inspired by advancements achieved during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The system delivered 100% accurate results within an hour of in-field sample collection on a commercial fresh produce farm.

“The approach we’ve taken is using a fecal indicator called Bacteroidales as a risk marker,” said Purdue’s Mohit Verma, associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering. Verma and his team of nine postdoctoral researchers, graduate and undergraduate students published their findings in the journal Biosensors and Bioelectronics. Krishi, a startup company where Verma serves as chief technology officer, is licensing the technology through Purdue Innovates Office of Technology Commercialization.

“The approach we’ve taken is using a fecal indicator called Bacteroidales as a risk marker,” said Purdue’s Mohit Verma, associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering. Verma and his team of nine postdoctoral researchers, graduate and undergraduate students published their findings in the journal Biosensors and Bioelectronics. Krishi, a startup company where Verma serves as chief technology officer, is licensing the technology through Purdue Innovates Office of Technology Commercialization.

“The goal has been to estimate what risks might be present in fresh produce operations from nearby animal operations or other wildlife,” Verma said. Typically, this is done by measuring pathogens. If pathogens are present on the crop, it is discarded. But detecting pathogens at a low level, in compliance with regulatory requirements governing products with a short shelf life, presents challenges.

The technology Verma uses is called loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). The team has implemented it on innovative, paper-based devices for rapid results for agricultural uses. Previously, Verma’s team developed these tests for bovine respiratory disease and COVID-19.

“To our knowledge, this work represents the first demonstration of a portable LAMP testing platform implemented on a fresh produce farm,” the coauthors wrote in their journal article.

The new paper also refines previous results published in the journal Food Microbiology by lead author Jiangshan Wang, who earned his doctorate at Purdue in agricultural and biological engineering this year, Verma and their associates.

Bacteroidales is a fecal organism found in swine, poultry and cattle. Most foodborne pathogens linked to fresh produce, including E. coli and salmonella, originate in the intestines.

The Purdue team tested the system on a commercial lettuce farm in Salinas, California, and in a field next to the Purdue Animal Sciences Research and Education Center in West Lafayette, Indiana. Microbial samples were collected from plastic flags that were placed throughout the testing area.

Small flags made of plastic sheets collected bioaerosol samples for a week in Verma’s experiments. The experiments compared testing in the field and in the laboratory. All of the flags were brought to the laboratory for quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing. “That allows you to measure Bacteriodales and therefore the level of fecal contamination,” Verma said.

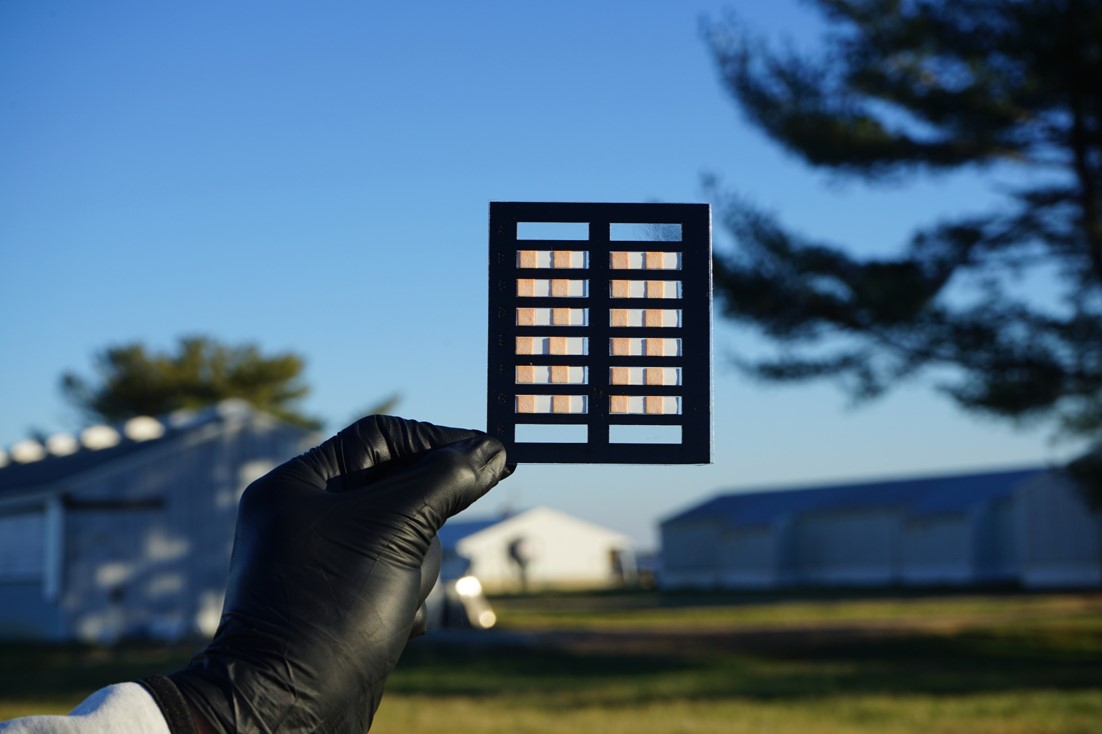

But with the new assay kit, which consists of a drop dispenser, paper-based devices and a heating imager, growers can carry out the entire process in the field. After swabbing the collection flag, they put in it a drop dispenser that is preloaded with liquid to dispense a specific volume.

The liquid dispenses into the paper devices that contain the compounds needed to detect DNA in the samples. The paper device then goes into a heating imager. An hour later the device reveals how much Bacteriodales is present. The assay provides quantitative test results that confirm what growers, following visual inspection, often intuitively suspect is happening in their fields.

The field test results agreed 100% with laboratory results. They involved samples that included very low or very high concentrations of contamination. It’s challenging to get the full variation of contamination levels in field testing, but that is part of ongoing work, Verma noted.

The field tests lacked samples containing an intermediate range of contamination, which would have yielded most of the mismatches. Still, the assay can detect as few as three copies of Bacteroidales DNA per square centimeter. Verma estimates that tests involving a full range of contamination would achieve agreement with laboratory testing of above 90%.

Low levels of Bacteroidales indicate a low-risk location. High levels signal the need to take precautions. High levels of contamination would be 1,000 copies of DNA per square centimeter found on a test pad, with one copy corresponding to one cell from any of a broad class of bacteria. Low levels would be 10 copies per square centimeter.

“The biggest limitation is we don’t really know what these numbers mean yet,” Verma said. “What about in between? Where do we set the threshold? That’s part of ongoing work,” he said.

Lead authors Wang and Simerdeep Kaur, a PhD student in the Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, developed the assays and the paper-based devices and conducted the field testing. Coauthors in the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering and the Elmore Family School of Electrical and Computer Engineering developed the heating imager. Other coauthors assisted with field testing preparations and device optimization.

The work demonstrates the Verma group’s ability to go from developing something new in the lab to testing it in the field. “Not everyone can do that, and you definitely can’t do it alone. That’s what is indicated by the list of authors you see,” Verma said.

Funding for this project came from the Center for Produce Safety, California Department of Food and Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service. Verma disclosed the innovation to the Purdue Innovates Office of Technology Commercialization, which has applied for a patent to protect the intellectual property. OTC issued a license for the technology to Verma’s company, Krishi. Krishi is currently raising capital for commercialization.