Who designed the Gateway Arch? & other footprints left by landscape architects on Purdue’s campus

When you imagine Purdue University or pull up images in a Google search, it’s likely that you see pictures of herringbone brick pathways, limestone pillars with metal arches and greenspaces full of students. Not too long ago, this wouldn’t have been the case. The Purdue University of the 1970s would be unrecognizable to most people on campus now.

John Collier, however, still remembers the asphalt drives, parking lots and the busy highway that once cut campus in half. Collier arrived at Purdue in 1979 as a student in environmental design, a major in a college that no longer exists. One semester in, he was so awed by the miniature model of campus in Purdue Memorial Union that he knew he had to change his major to become one of the people who maintained it: a landscape architect.

While the smell of burning styrofoam and hot-wire cutting deterred Collier from modeling, he did become passionate about designing outdoor spaces that bring people together. He interned at the Facilities Planning Office as an undergraduate and stayed there for 30 years, eventually becoming the director of campus master planning in 2004.

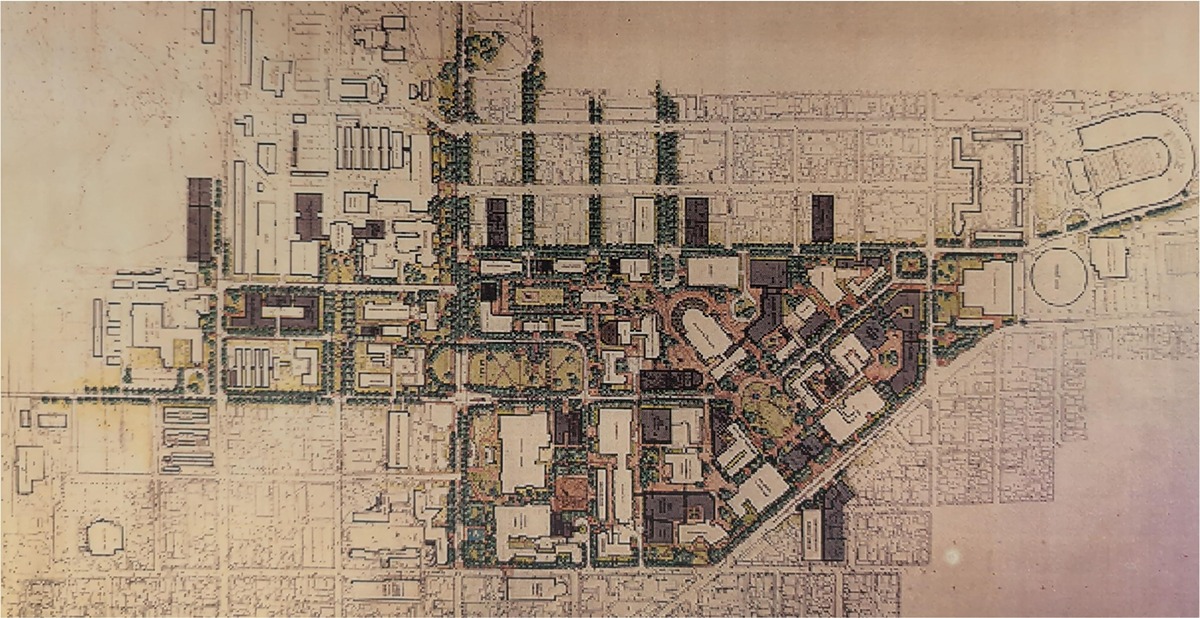

“I was here when the Campus Master Plan was updated in 1986 by Sasaki Associates. I had just graduated. I was at the right place at the right time,” Collier said.

The 1986 Campus Master Plan, updated from the prior plan completed in the 1920s, helped transform the campus from unwalkable roadways to the artful outdoor spaces Boilermakers enjoy today. Although Collier is humble about his achievements, he played a role in designing some of the most famous landmarks of Purdue.

Landscape architects, both those working here for Purdue and those from landscape architecture firms we contracted, designed nearly every major greenspace on campus.”

- John Collier, Horticulture and Landscape Architecture Alumnus & former Director of Campus Master Planning

The Hello Walk Entrance:

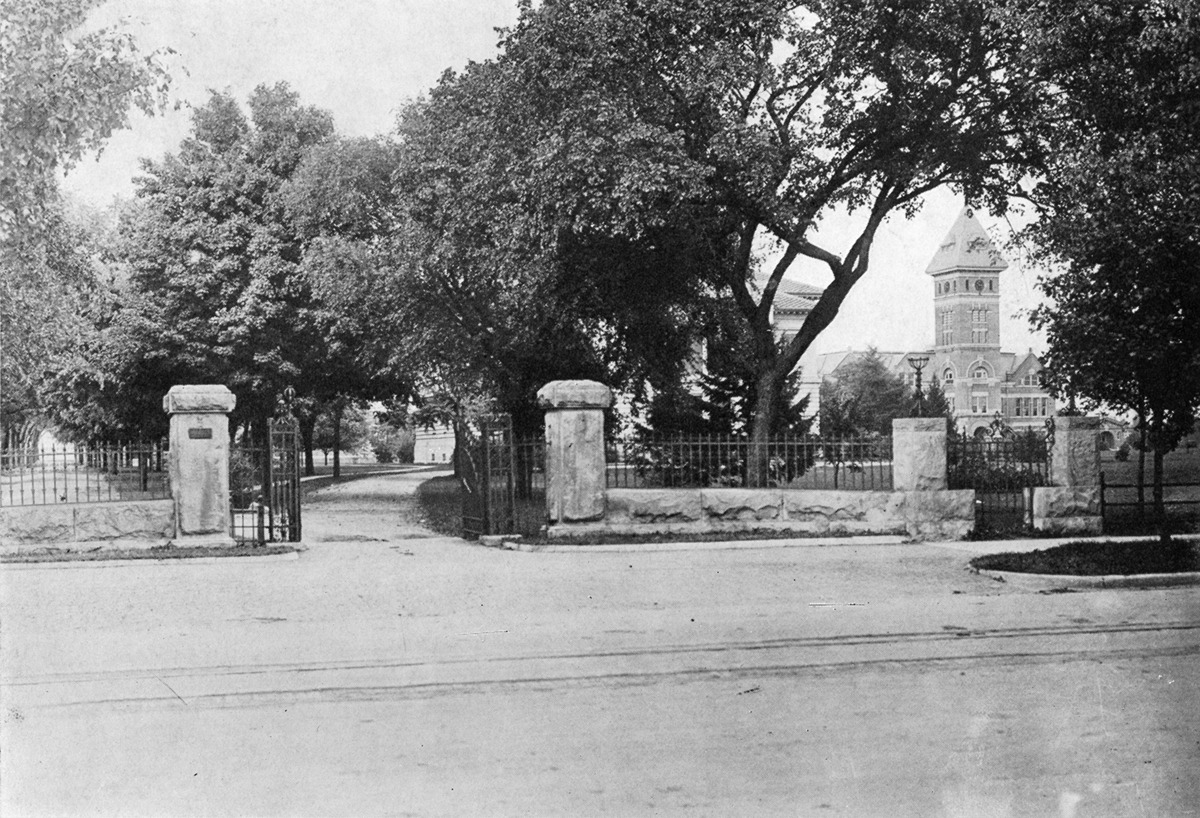

“My boss—the university architect Tom Schmenk—and I happened upon them out in a field behind the old 9th street warehouse. They were lying in the grass,” Collier said of the great limestone pillars that now sit on the edge of the Hello Walk. “They had been in storage for 40 years.”

One of Collier's first big projects after the 1986 Master Plan was figuring out what to do with the pillars. Eventually, he found pictures of them connected by an ornate iron fence gate at the entrance of Memorial Mall Drive when it had just been a carriage path. The pillars had been placed there in 1891.

In 1923, the class of 1897 added the lower stone walls and an ornate iron fence and gate to celebrate their 25th anniversary from graduation. You can still see where the original iron gate connected to the side of the pillars, and the‘97 chiseled into the stone still reads clear. But when the boulevard was widened for cars in the 1950s, the entire “campus portal” was removed.

Collier said, “The interesting thing was we rededicated this whole space in 1991 as part of the 50-year class gift from the class of 1951 that reestablished the Hello Walk. We’d installed them 100 years after they were originally installed, and we didn't know that until after the dedication.”

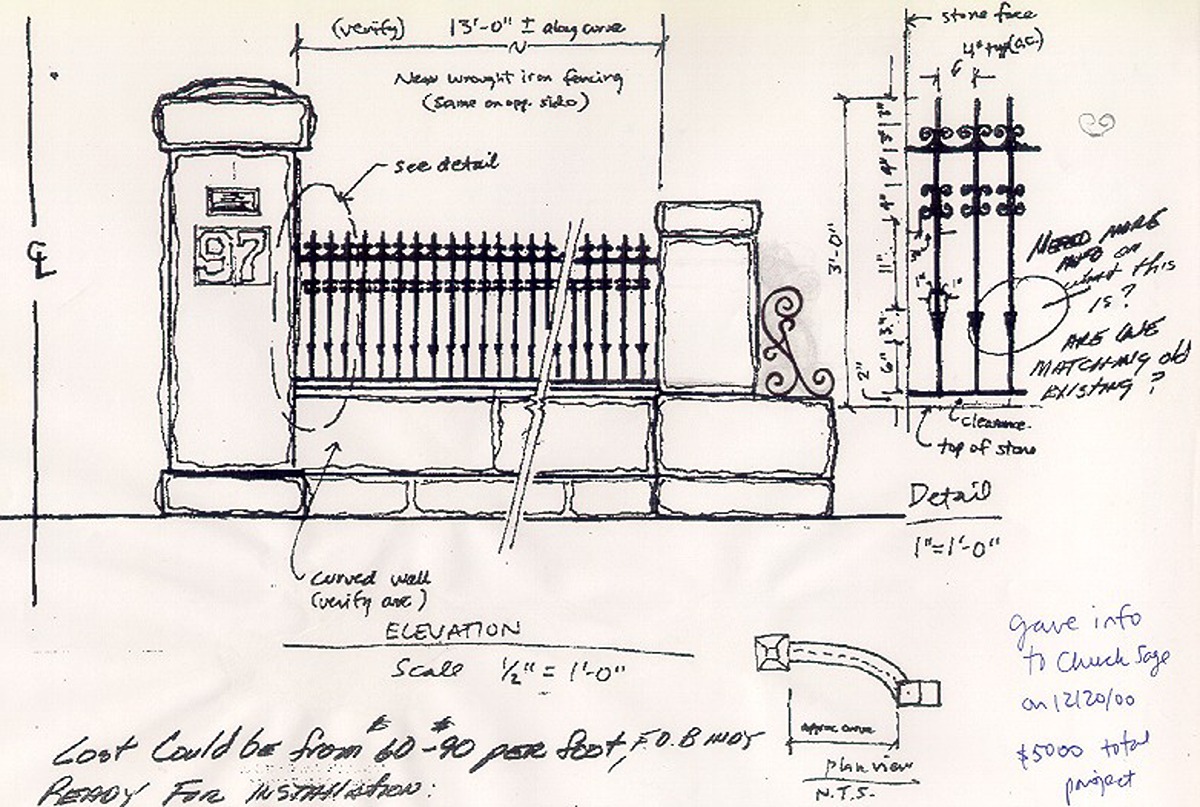

The class of 1936 and the grandchildren of the class of 1897 funded the restoration of the lower stone walls and the pillars. About a decade later, Collier patterned a new fence from the wrought iron fencing he saw in photos. He also made a sketch of how the campus portal originally looked, and the image is engraved on a plaque embedded in one of the pillars.

The Clapping Circle:

The area between the Purdue Memorial Union, Stewart Center and Heavilon Hall used to be all roadways and parking lots. Now, brick pathways bisect green mounds planted with trees on which students often tie hammocks to rest between classes. Tour guides lead prospective students and their families to the center of Academy Park to clap and hear the echo, claiming the area was designed with perfect acoustics in mind.

Collier says that the acoustic perfection was accidental. “This was one of the most highly-traveled pedestrian areas on the whole campus, and people came from all directions. So rather than just make it all one big plaza or put down flat lawn panels that would become mud paths, we put the seat walls in to direct people where we wanted them to walk and to take them to strategic building entrances. Then, we created this great central plaza in the center.”

President Steven Beering decreed the space Academy Park, claiming its inspiration was the outdoor classrooms of ancient Greek scholars. Collier agrees that this is closer to the truth. He planned for each hill to serve as its own classroom, far enough from each other so that teachers wouldn’t have to speak over one another. He also thought the space could be used for performances, and there are still panels on the sidewalls and electrical conduit installed under the central plaza to accommodate audio and lighting fixtures.

The Gateway Arch:

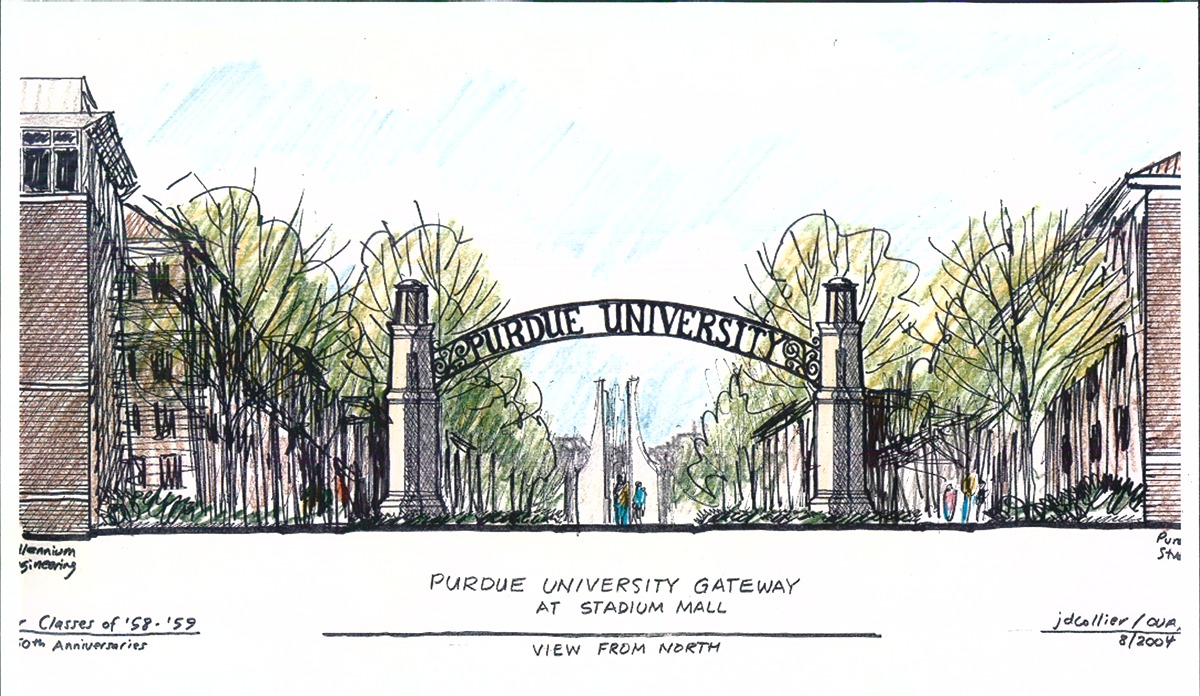

Graduating seniors wait in line to get photos in their robes in front of the great arch opening on the corner of Stadium Avenue and University Street. This arch, officially called the “Gateway to the Future,” was a gift donated by the classes of 1958 and 1959. Collier designed the original concept.

“Fred Ford was a Purdue alumnus and the executive vice president and treasurer for Purdue for decades. After he retired, he engaged me to develop a 50th-anniversary gift for his and his wife’s classes. I agonized over what I was going to do for them because I knew it had to be good, and I had other ideas and thought they were terrible. Literally the day before I was supposed to meet with him and his wife, Mary, I came up with this concept for the arch, and they loved it,” Collier said.

Collier drew on the gothic elements from Purdue’s rich history, pulling in the giant stone pillars reminiscent of those from the old campus portals and black metal streetlamps.

These three landmarks are far from the only history that Collier and other landscape architects made on campus. With the help of donors and construction contractors, they expanded bike paths, planted trees, designed courtyards, enhanced fountains, contracted statues and public art, placed benches and created paths connecting the campus community.

“People think that landscape architects just work with plants, but it’s so much more than that,” Collier said. “We design outdoor spaces to be accessible for people to use and enjoy. Walls, pathways, exterior spaces and many landmarks are designed by landscape architects.”

Collier worked for Purdue for 32 years, the last two for University Residences. Landscape architecture classes and professors—especially Don Molnar, a professor emeritus and chair of landscape architecture at Purdue—gave Collier inspiration and the foundational knowledge to understand the field, and the internship in the planning office gave him opportunities to create designs early on in his career. He’s since helped other landscape architects get their start in the same way—even Stadium Mall was designed with the help of a student intern from his office.

When Collier retired from Purdue, he took his expertise to the city of Lafayette, where he has served as the assistant director for economic development for eight years. He helps facilitate new projects with the mayor, city staff and landscape architecture firms. Collier also volunteers for the local Civic Theatre as a set designer, scenic artist and director.It wasn’t me doing this alone. I was a part of a great team of other landscape architects, building architects, civil engineers, electrical engineers, mechanical engineers. We all worked really, really well together in our office and collaborated to make all these great projects. I was lucky to be a part of Purdue’s planning team at the time I was and to have the opportunity to design so much for campus. I love this place.”

- John Collier, Horticulture and Landscape Architecture Alumnus & former Director of Campus Master Planning