Could a fungus be behind the Salem witch trials?

Mass hallucinations and paranoia. Seizures and bodily convulsions. From 1692 to 1693, the town of Salem in the Massachusetts Bay Colony tried approximately 200 people for their crimes of witchcraft. Within that year, 14 women, six men and two dogs were killed on suspicion of working for the devil. Politics, fear, religious superstition and social ostracization have all been credited as kindling for the witch trials.

But could fungi also have been to blame?

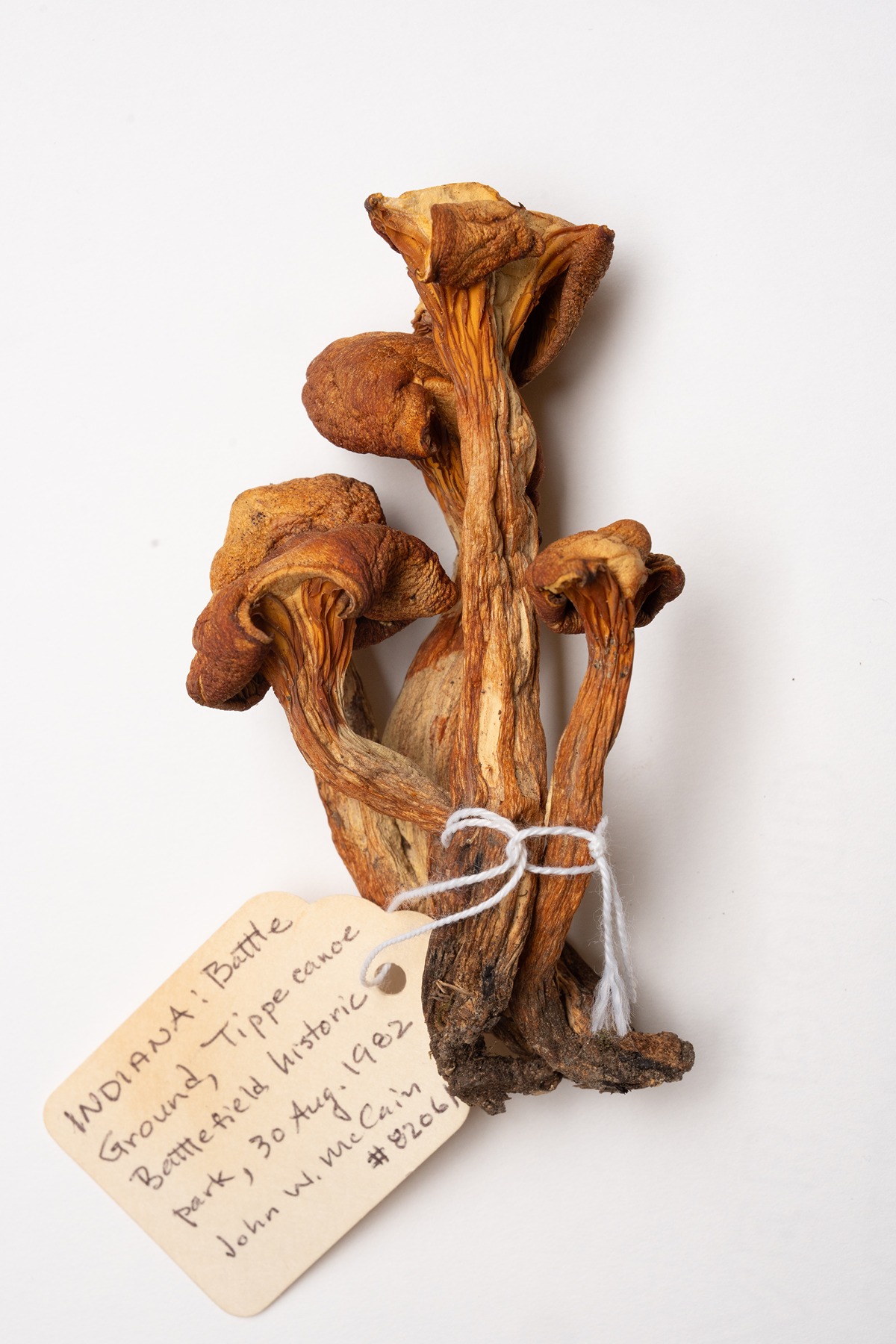

Under the guise of amber waving grains, the fungal pathogen Claviceps purpurea, or ergot, explodes from its capsule set in the rye seed head and releases spores across the rest of the unsuspecting cereal-grain fields. This fungus has infected crops, and in turn, food supplies for more than a millennia.Even for Rabern Simmons, the Purdue University Herbaria’s curator of fungi, mushrooms’ troubled reputation is difficult to ignore. “I think there's always been a negative connotation of mushrooms and fungi,” he said. “These organisms just erupt out of the soil in a rather crude shape. Think of the words we use to describe them: rot and decay, mold and blight. Historically, they’re seen as dangerous and associated with witchcraft and curses.”

That association is particularly strong with ergot. Approximately 130 epidemics in Europe from 591 to 1789 A.D. are thought to have been caused by ergot poisoning.

Some alkaloids, a chemical class of nitrogenous and organic compounds derived from plants and fungi — including the alkaloid used to create LSD — are active in the ergot fungus and have major physiological effects on humans. Convulsive ergot poisoning can cause hallucinations, body spasms, nausea, seizures and vomiting. Gangrene ergotism restricts the blood vessels in extremities, making fingers and toes blacken, die and fall off.

“What was most upsetting is that there was such a loss of sensation that your finger could fall off and you didn't feel it fall. Europeans considered that lack of feeling as proof an evil spirit was causing it,” Simmons explained. “Also, one of the early symptoms of ergotism is something colloquially known as ‘holy fire’ or ‘Saint Anthony's fire,’ a general burning sensation that most affected young people, like the accusers. People said that this was your body preemptively burning in hell.”

Rye being the pathogen’s favorite host was also considered an act of God. Rye was a cheaper crop than white wheat and other grains less susceptible to ergot. So, communities that could afford only rye were more likely to end up with ergotism, a trend that people historically claimed meant that God was punishing the lower class.

Psychologist Linnda R. Caporael, credited as the first to theorize that ergotism might’ve played a role in the Salem witch trials, published a hypothesis in Science in 1976 that the cold winter and wet spring of 1691 would’ve been ripe conditions for ergot to flourish in the town’s rye crop. Simmons said towns like Salem also typically stored their grain in damp conditions, which could have led to further contamination.

Nine-year-old Betty Parris and 11-year-old Abigail Williams were the first accusers of witchcraft, blaming two socially ostracized neighbors and a servant for their violent fits, strange visions and burning sensations. While these symptoms could be explained today by ergotism, Salem’s doctor could only describe the illness as something supernatural.

Simmons said it was not just the accusers infected by ergot “but also the accused and the rest of the town were likely suffering from ergotism. Everyone was terrified of what was going on around them, whether it be convulsions, necrosis or hallucinations. It wasn't until the next year, after a hot and dry summer, that the ‘witchcraft’ disappeared — likely because there was no ergot the following season.”

Simmons is looking to change the negative worldview mushrooms have acquired. Among this group of decomposers, there’s the bad and the dangerous, but also the medicinal, the delicious and the recyclers. Beyond the hallucinogenic properties of the fungus and LSD, people have used ergot for centuries to stop bleeding in mothers after giving birth. It could also potentially be used for treating migraines and Alzheimer’s disease.

As it turns out, ergot even benefits rye. “Ergot gains its nourishment from the plant, but it’s believed that it protects the cereal from insect damage because the insects don't want to eat it either,” Simmons said. “Historically, some people saw this as a plant disease, but others thought if you had a lot of black spots of ergot in the fields, yields were going to be abundant.”

In his own research, Simmons has seen similar stories between fungi, their environment and people. He specializes in the chytrid group of microscopic fungi; one species was discovered to infect frogs in 1999. Only in 2022 was that fungal pathogen then linked to an increase of malaria cases because there were fewer amphibians around to control the mosquito population. All members of an ecosystem are connected, ties that Simmons says will only become clearer in climate change.

Just because a fungus is an inconvenience for us doesn't mean that it's necessarily a bad thing. But only when we recognize it as a problem do we pay attention.”

- Rabern Simmons, Curator of Fungi at the Purdue University Herbaria

This Tremella mesenterica is better known as “witch’s butter” and grows off of trees.

This Tremella mesenterica is better known as “witch’s butter” and grows off of trees.