Agriculture professors elected to rank of AAAS Fellow

Purdue College of Agriculture professors Stephen Cameron and Bryan Pijanowski have been elected fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Election as a fellow honors members recognizes that their efforts on behalf of the advancement of science or its applications in service to society have distinguished them among their peers and colleagues.

The AAAS cited Cameron “for distinguished contributions to the field of insect evolutionary genetics, particularly using mitochondrial genomics to better understand insect evolution, systematics and genomic biology.”

The AAAS cited Pijanowski “for distinguished contributions to documenting and interpreting the soundscape ecology of natural and human dominated systems across the world.”

Both Purdue AAAS fellows expressed gratitude for the highly selective honor. Only 471 fellows were elected in 2024 from its global membership, which spans more than 90 nations.

“There aren’t too many entomologists or evolutionary biologists who are AAAS Fellows,” said Cameron, professor of entomology, making the honor doubly special.

Pijanowski, professor of forestry and natural resources, said, “This is indeed one of the most marvelous recognitions to happen to me in my career, even given all of my travel and very unique experiences in some of the most remote places in the world. It is one of the top honors in all of science. I’m truly humbled.”

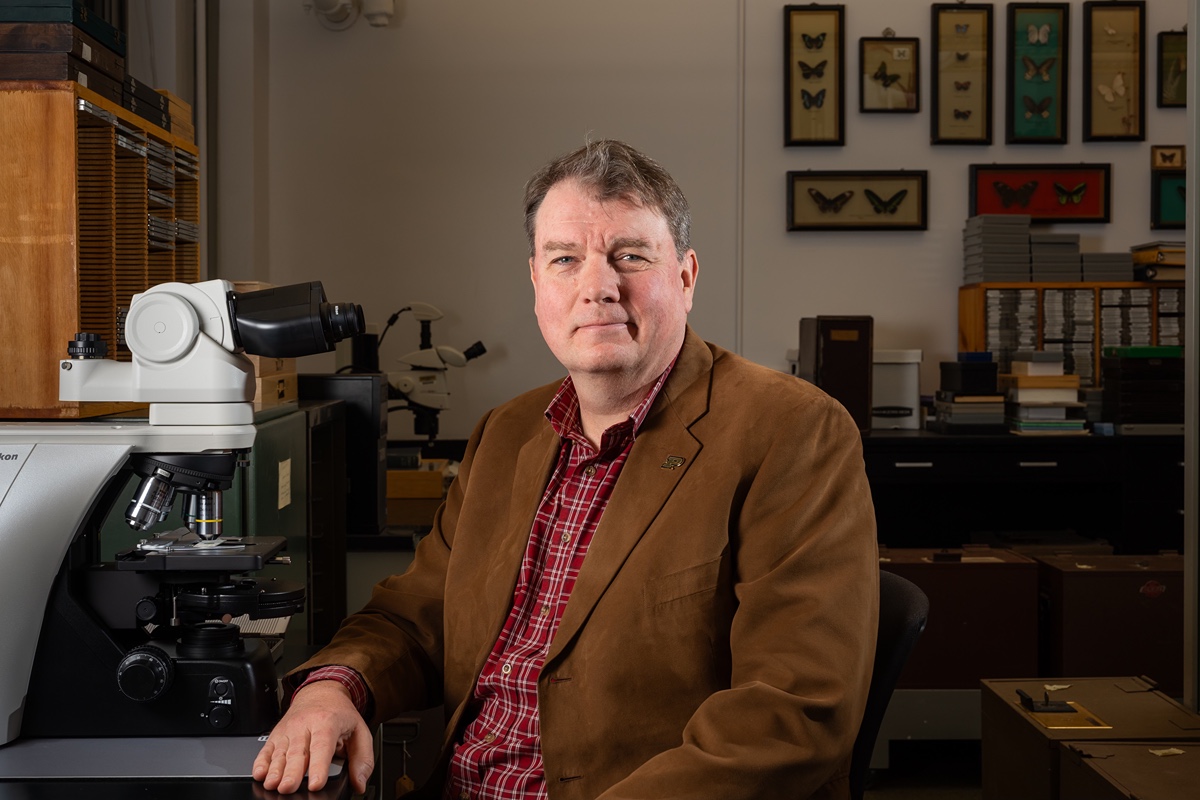

STEPHEN CAMERON

“As a specialist in evolutionary genomics, Stephen studies how insect genetic material changes over time,” said Bernie Engel, the Glenn W. Sample Dean of Agriculture. “Stephen is an outstanding, highly inquisitive general scientist who has contributed to understanding our natural world even as he has also pursued projects with more applied impacts.”

Cameron’s fundamental research on developing tools for using DNA to identify and define species has, for example, had a practical economic impact. From 2010 to 2018, he and his associates applied their work to a system of Asian fruit fly pests that limited fruit trade from Africa to India and China.

“When we demonstrated that the pest fruit flies were all the same species, Bactrocera dorsalis, we were able to advocate for bringing down those barriers, which liberalized trade between 4 billion people,” Cameron said.

“Grains keep you alive. Fruits keep you healthy,” he said. “But there’s a step beyond staying alive, and it starts with fruits, micronutrients and small amounts of cash within otherwise subsistence agricultural systems.”

When Cameron and his associates carried out that work, Africa was subject to extensive controls on mango exports. “That all basically came down to what is a species,” he said. Defining a species often becomes an esoteric question, except when conservation law and biosecurity rules become based on the answer.

“I’ve been able to come at this work with genomic evolution and how genomes evolve in the speciation situations,” he said. “There’s still a lot of fundamental science to be done even in fields like genetics. We often don’t know where these things are going to lead.”

Cameron earned his PhD studying one-celled organisms called protozoa at the University of Queensland in Australia. As a generalist, he has moved from one insect group to another every five or 10 years. “I’m not wedded to any particular insect group, although I have my favorites,” he said. “It’s been a few years since I did any work with moths, but it was a while there where I did nothing but moths.”

A native Australian, Cameron has moved back and forth between his home country and the U.S. throughout his career. Coming from the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia, he joined the Purdue faculty in 2016.

“Scientific immigration contributes to the cross-pollination and shaking up of ideas,” Cameron said. His fruit fly work serves as an example. He came to the problem after a long series of failed attempts by others to address the problem.

“It took outsiders looking at the system and applying new data sets and new ways of thinking about species limits in the group to make actual progress,” he said.

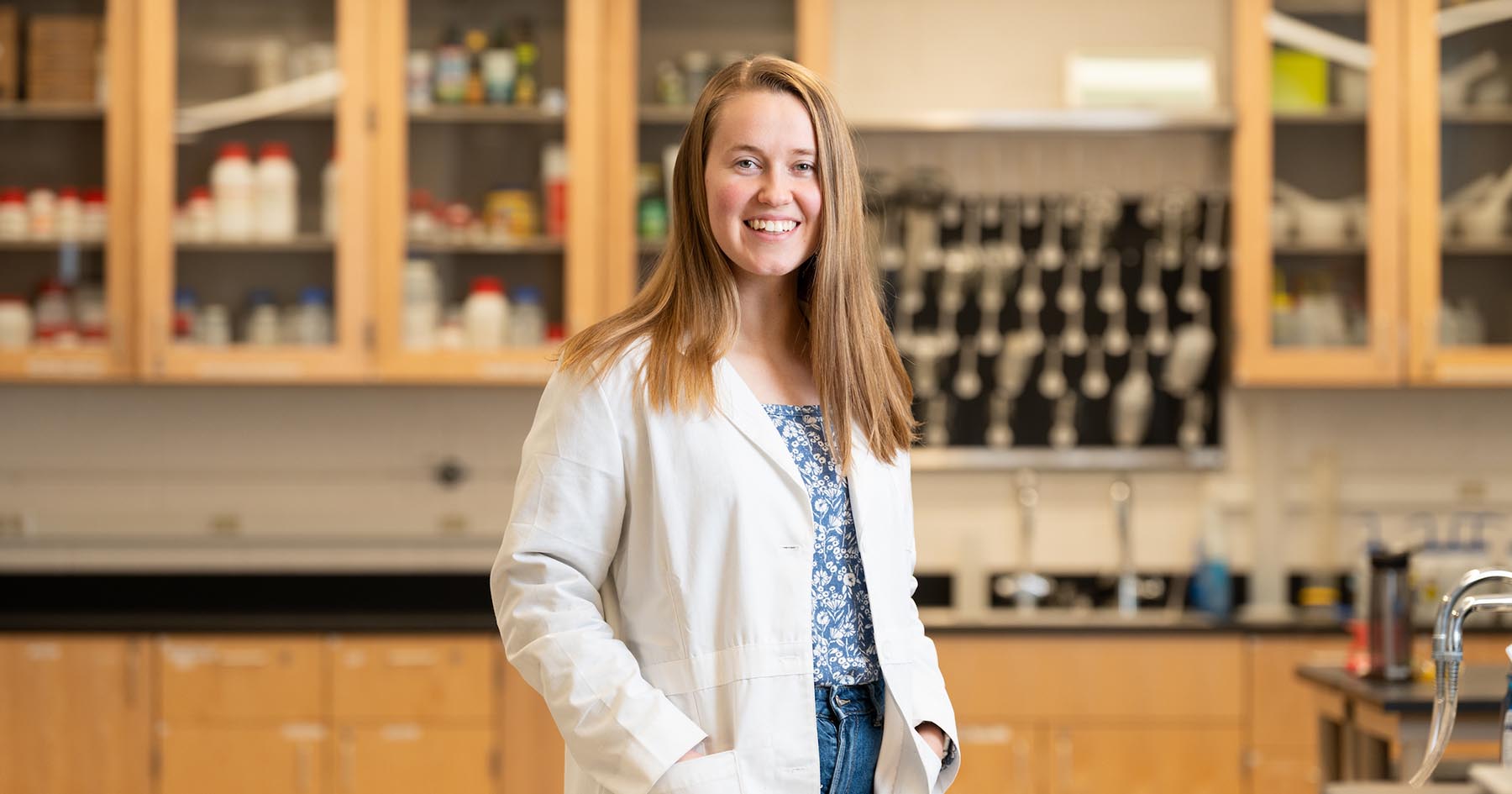

BRYAN PIJANOWSKI

“Bryan makes what he calls ‘digital fossils,’ representations of the sounds of a place that will have enduring scientific value,” said Engel. “Scientists a hundred years from now will be able to listen to his digital recordings and glean new insights into the transformations that the Earth has experienced.”

Pijanowski joined the Purdue faculty in 2003, then became founding director of the Center for Global Soundscapes in 2013. His work has taken him around the world, to Central Asia’s Gobi Desert, the glaciers of Patagonia in South America, the Miombo Woodlands of East Africa, and the paleotropical rainforests of Borneo.

He has made over 6 million audio recordings at more than 60 study sites globally. He depends upon artificial intelligence tools to scan his sound files for identifying various animal species. Thus far, he has studied at 28 of the world’s 32 ecosystems. Everything is fair game, from the impact of hurricanes on coral reefs in Costa Rica, to the sounds of a southeast Indiana woodland environment before and during a solar eclipse.

“I’ve gone to amazing places. I’ve collaborated with truly exceptional people who inspire and educate me about the place I am studying. And I consider myself fortunate to have done that,” Pijanowski said. “I have tried to follow in the footsteps of my heroes, great scientists like Alexander von Humbolt, a biogeographer and naturalist. He traveled the world to understand nature.”

Likening himself to a 21st-century naturalist, Pijanowski has followed a similar career path. “I’m going to places, comparing-contrasting them, and trying to understand why they’re different and maybe how they’re similar just by listening and using sound as a basis of measurement. But I use advanced sensors, create big data, and use deep learning to uncover complex patterns in digital audio data. I’m also with my students, who also inspire me with their insights. It is great to share the excitement of learning about new ecosystems with the next generation of scientists.”

In the first chapter of his textbook, Principles of Soundscape: Discovering our Sonic World, Pijanowski traces the discipline’s roots to Finnish geographer Johannes Gabriel Granö’s work in the 1920s. Granö mapped the senses of a place, including sight, sound and smell. Later came F. Murray Schafer, a Canadian musician, who popularized the term “soundscape” in his book Tuning of the World, published in 1977.

“Schafer wrote about natural sounds and that humans were orchestrating the soundscapes of today. They were responsible for changing the habitat but also introducing sounds of culture and their ways of life,” Pijanowski said.

In the 1980s, natural sounds recording expert Bernie Krause highlighted the existence of wild soundscapes. “These are pristine spaces that have been shaped by ecological and evolutionary processes.”

Then came Pijanowski and his transdisciplinary team that placed soundscapes into scientific and ecological contexts.

“Many threads have evolved to where we’re thinking about how a place is defined as its unique soundscape, an acoustic fingerprint of the sonic animals and geophonic climate dynamics of a location, and how, as an ecologist, I can interpret it to improve our knowledge to advance conservation efforts,” Pijanowski said. “Indeed…sound is a universal measure. It’s everywhere. And if you follow it, and listen, you get to intellectual places that just amaze you.”