Using sun shadows and simulations to combat snowy roads

A midwestern winter is no joke, especially for people driving through it on daily commutes and grocery trips. Not only must individual Hoosiers prepare for snowy roads, but so must the Indiana Department of Transportation (INDOT).

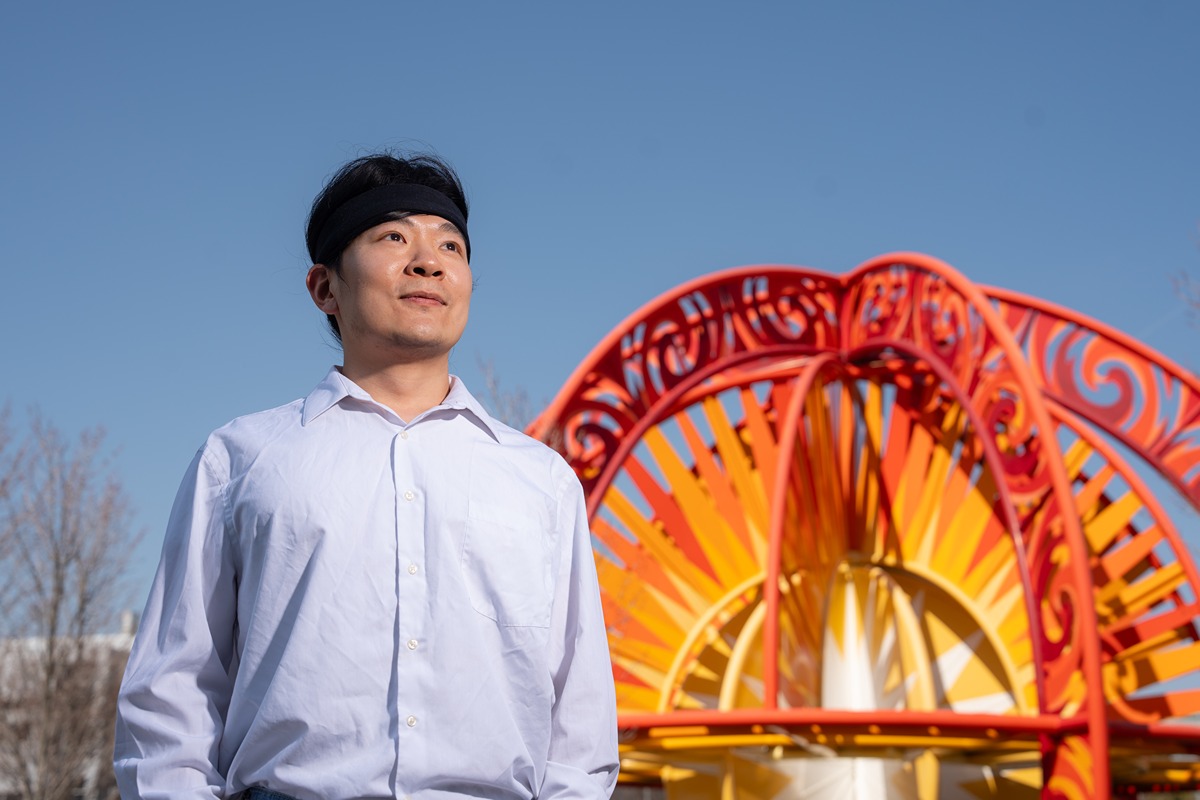

Yaguang Zhang, a clinical assistant professor of agricultural and biological engineering as well as agricultural sciences education and communication at Purdue University, said that “ice and snow removal is the number one concern for INDOT and many other departments of transportation during the winter. Here in Indiana, we have a lot of snow, and our temperature can drop significantly, so safety is INDOT’s top priority. Because of that, they may unintentionally overapply chemicals to keep roads clear.”

These chemicals can be salts or liquid brines. They either prevent ice from sticking to the road if applied prior to a storm or reduce the temperature required to melt it after a storm.

Across the 70% of U.S. roadways affected by snow and ice, plows and treatment vehicles take long, pre-set routes and apply the same amount of chemicals throughout. While this does keep all roadways clear, some roads will get far more treatment than necessary.

This excess is expensive. The U.S. pays $2.3 billion to manage snow and ice on highways every year, including the application of 15 million tons of road salt. Those chemicals can damage metal, including the bottom of your car and metal bridges, which cost the U.S. another $5 billion per year.

Overapplications of salts and brines burden the budget and the environment. Zhang said, “The chemicals have to go somewhere. If we apply a lot, it will affect vegetation next to the highway. We have trees and grass beside roadways so it looks nice to drivers and to protect the environment. If it was bare soil, we would lose the nutrition in that soil and even in the fields next to it.”

In soil with too much salt or brine, the plant is blocked from uptaking water, which can cause it to brown and die, leaving the land unprotected.

Zhang was funded during his PhD under James Krogmeier, Purdue professor of electrical engineering, by INDOT to reduce salts and brine applications by creating a map that would show where the chemicals are most needed and where snow or ice might melt on its own.

To do this Zhang turned to “sun shadows,” those shadows caused by trees, buildings and other obstacles blocking the direct path of the sun. Sun shadows decrease exposure to the sun’s light and heat, making that ground cooler and less able to melt the snow and ice.

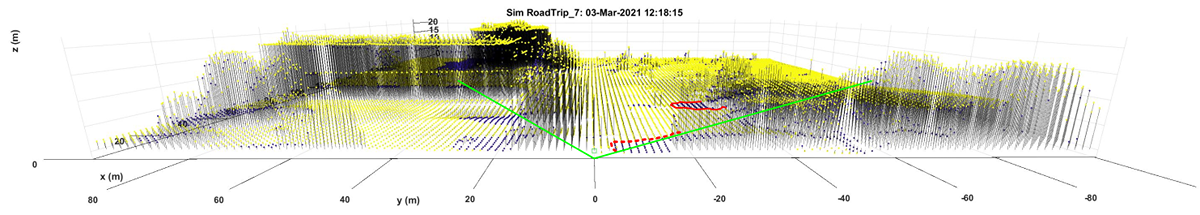

Zhang used a database of “Light Detection and Ranging,” or lidar information, to help build his map simulating where sun shadows would occur throughout the day. Lidar technology was used all across Indiana from 2016 to 2020 for the U.S. Geological Survey’s 3D Elevation Program, which included efforts from Purdue civil engineering professor, Jinha Jung.

“You essentially shoot laser beams toward the ground and measure how long they take to bounce back. That round-trip travel time can be converted into height,” Zhang said. “If you look at the raw lidar point cloud, it doesn’t just capture a single height—it records multiple surfaces at different locations. Trees, buildings, and even cars reflect strong signals, helping us build a detailed 3D map of the environment.”

Zhang used the known course of the sun to calculate and predict what from the 3D maps would block sunlight’s direct path throughout the day. From the sun shadow maps, he built simulations every 15 minutes throughout a day to calculate the sun energy absorbed by the road surface for periods of interest. Persistent sun shadows meant less energy absorbed by the road and indicated the areas of greatest need for snow and ice treatments.

This is just the beginning. Zhang said, “We want to try to find a linkage between the sun energy absorbed by the surface to the right amount of snow and ice treatment that we want to apply so that we reduce the application without sacrificing the effects.”

INDOT can currently use the map to pay special attention to certain parts of the Indiana highway systems that have more persistent sun shadows. Zhang is also collaborating with Darcy Bullock, a professor in civil engineering, on the Bullock lab’s project creating a “smart snowplow” that would be automated to drive itself around and spray an amendable amount of brine for each precise location.

The sun shadow map could also be useful for farmers. The success of many crops, like corn, is dependent on how much intense sunlight the plants can get throughout the growing season. While farmers have a general idea of how much sun their field gets, there is no precise, site-specific data for them to rely on.

“If there’s a tree next to your field, we will see it. If you have a terrain change in your field, we will see it,” Zhang said. “In different locations, we will see the sun shine on the crop at different angles with different intensities. What if you knew exactly where the shadows would fall, and even where they would be based on the height of your corn? You could better plan and organize your farm, adjusting the space between rows, plant north to south, east to west or even at a 45 degree angle, so that you locally enjoy the most sunshine. It could also inform canopy management for orchard planting and pruning.”

Growers interested in renewable energy could use the same simulation to see where it would be most effective to place solar panels in their field without them casting too much shadow on their crops.

Zhang also was able to exchange the sun in his map for electromagnetic waves. This allowed him to map the coverage of cell towers and where service, particularly in rural areas, is being blocked by terrain and other obstacles. Community leaders can use this to inform which areas have the greatest need for increased technology access.

Currently, Zhang’s sun shadow map is static. The original project simulated a long stretch of highway of interest to INDOT, but it could generate high-resolution simulations for any road or location in Indiana if given enough storage space and time.

As Zhang looks forward to increasing the scope and accuracy of this map with future graduate students in his lab, he said weather could be an important direction forward. “We are proposing fusing our current sun shadow map with both historical weather information and future weather forecasts, to adjust the application rate or the map accordingly.”

Without even considering the weather, the simulator can grow large quickly and require significant computing power. Zhang plans to collaborate with the Purdue Rosen Center for Advanced Computing (RCAC), which can help him store and process the big datasets. Zhang connected with RCAC during the Science-i Bridging Worlds Big Ideas Competition, where he won third place for his sun shadow simulation proposal. Science-i is a global data repository and a network of scientists processing and sharing that data.

There are several different directions for the sun shadow simulations and map to improve, and Zhang is committed to keeping it public so that INDOT can keep the roads clear, telecommunications companies can increase rural connectivity, and farmers can make decisions to best manage the sun in their fields. He’s also made the simulation and its software open source, so that others who have more ideas for how to use it could do so.

“If people are seeing the value of our research and are willing to take it further, we are happy to help,” Zhang said. “It means our idea goes further, more things get done, the research generates larger achievements and we help more people.”