Purdue researchers find new ways to track invasive species

Lidar and satellite imagery track the density and greenness that mark the presence of invasives

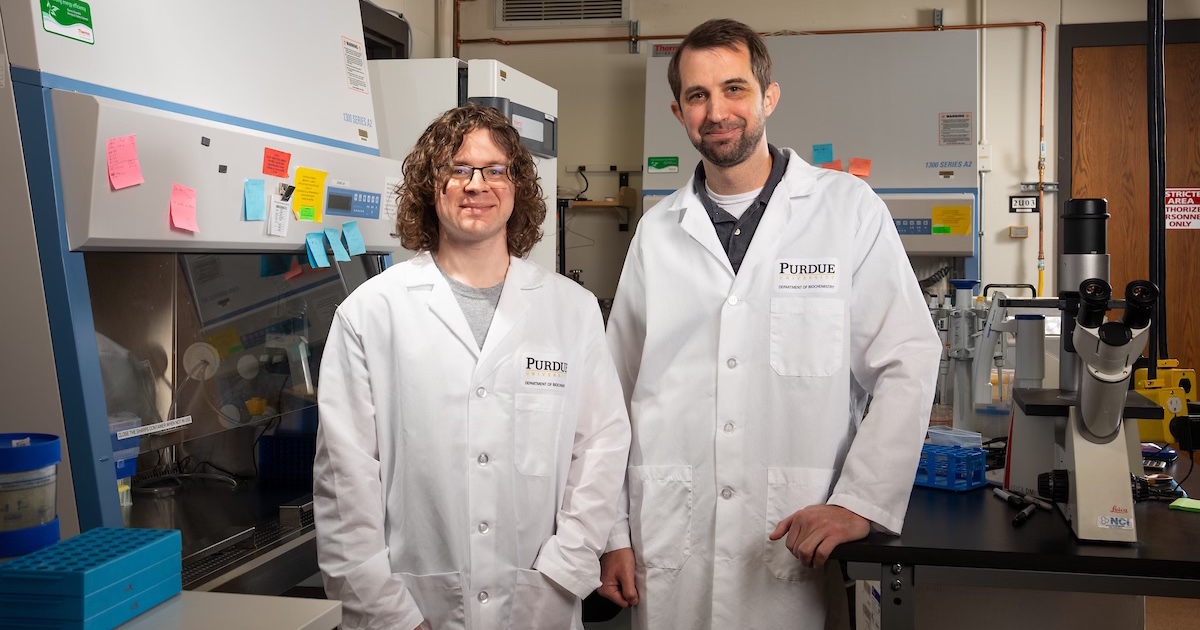

We tend to think all green landscapes are healthy. But Brady Hardiman, an associate professor of forestry and natural resources and environmental and ecological engineering, knows that’s not always the case. In fact, if it’s early or late in the growing season, a very green landscape on satellite imagery can be a sign of invasive species.

“Invasive buckthorn tends to leaf out earlier, and retains its leaves later into the fall,” says Hardiman. “And bush honeysuckle retains leaves into December when all the native species have long since gone dormant.”

New work by Hardiman and his colleagues uses satellite imagery and the innovative addition of lidar data to track invasive species. Satellite images spot excessive greenness, while the innovation of using lidar shows the canopy density that marks the presence of invasives.

“Detecting invasive shrub species is particularly challenging in large areas like the Chicago region due to the extensive area, labor demand and associated costs,” says Dennis Heejoon Choi, formerly a postdoc in Hardiman’s lab who was also advised by Songlin Fei, director of Purdue’s Institute for Digital Forestry. He is now an assistant professor at Dankook University in South Korea. “This work demonstrates how large-scale, high-quality remote sensing data can support the accurate detection of these shrubs, with validation provided by regional forest managers. The resulting invasion map will be valuable for urban forest managers seeking to identify and eradicate invasive species efficiently.”

More than 75 percent of Chicago area forests showed evidence of invasive species, composing over a third of all trees. Many of these species, including buckthorn and bush honeysuckle, were initially introduced as ornamental garden plants, prized for their quick growth and lush greenness. These species, long since escaped from gardens, are problematic for native forests.

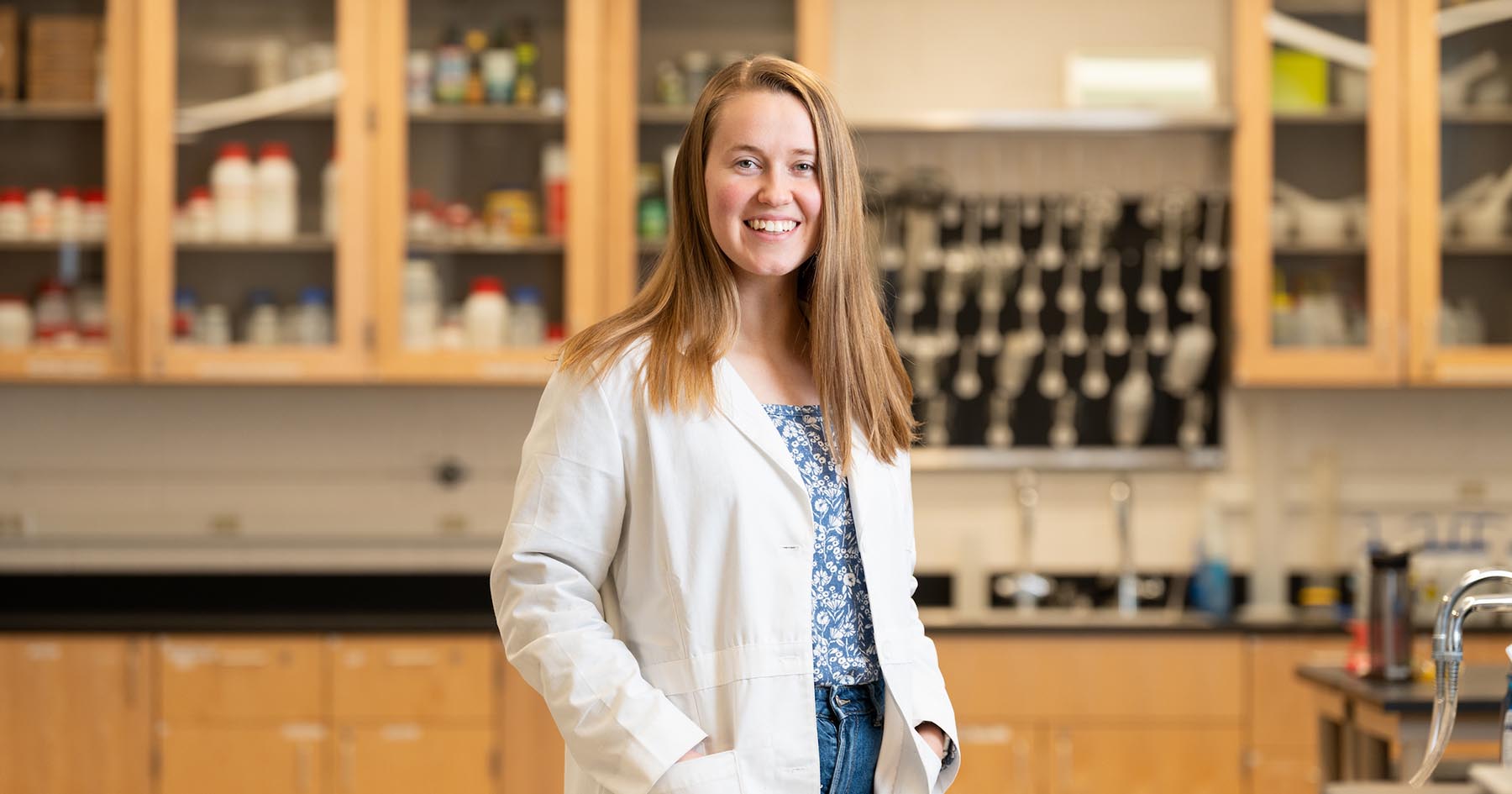

“Shrubby invasives are one of the biggest challenges in the management of natural areas in much of the US,” explains Lindsay Darling, who earned her PhD at Purdue and is now the data and GIS administrator of The Morton Arboretum outside Chicago. “They form short, dense canopies that keep sunlight from reaching the forest floor. This prevents other plants and trees from growing underneath them.”

Since native forests – especially oak – support animals and native plants in a way that invasives don’t, protecting them is a priority.

“Understanding the extent of these shrubs is critical to managing them,” Darling adds. “Land ownership in urban areas is often quite fragmented, with residential, institutional, and commercial properties adjoining publicly owned natural areas. Managing invasive species is best achieved at a landscape scale, where they are removed not by parcel boundaries but across them.”

Although the work took place around Chicago, shrubby invaders are a problem across much of the country and beyond. The team is seeking ways to make the data accessible to community members who aren’t technical experts. Darling has developed an online tool for looking at invasives data, and has hosted workshops to show how the research can be applied to real-world problems.

Brady Hardiman leads the Forest and Urban Systems Ecology Lab (FUSE). Besides Hardiman, Fei, Choi and Darling, the team included Purdue chemical engineering undergraduate Isaac Morton. The results of the team’s research will be published in the May issue of the journal Urban Forestry and Urban Greening.

This research is a part of Purdue’s presidential One Health initiative, which involves research at the intersection of human, animal and plant health and well-being.